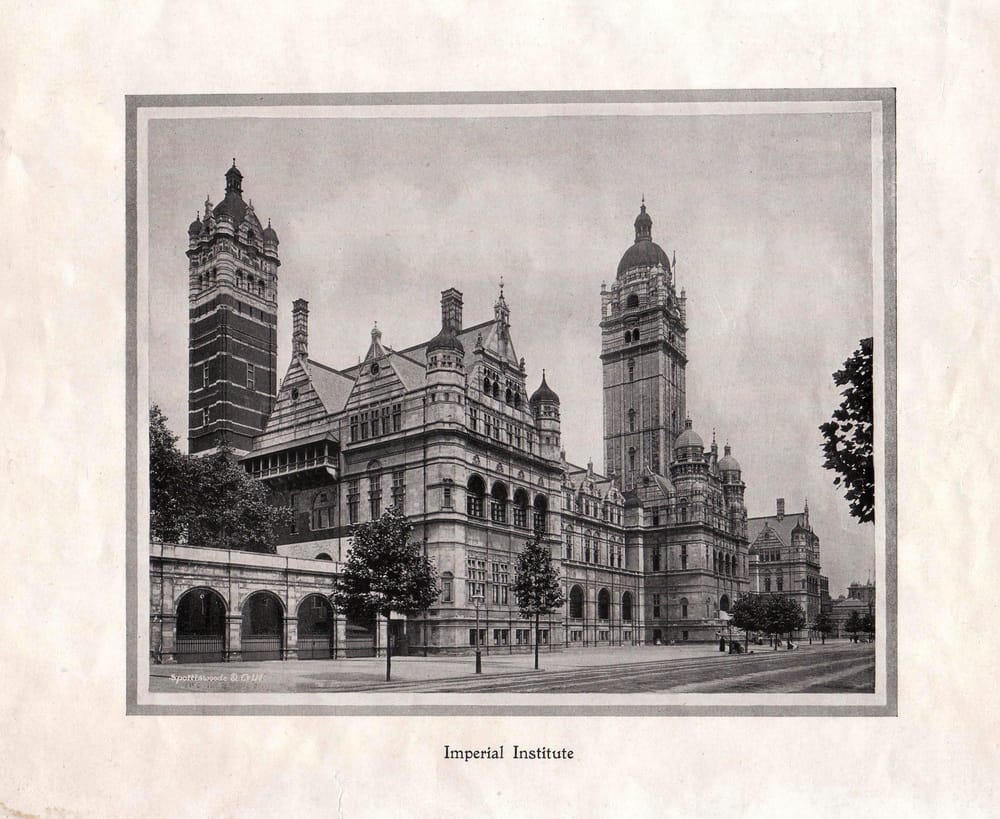

Glimpses of the past – the Imperial Institute

A look at our campus as it once was

When construction began on the grand Imperial Institute in 1887, fears were already being expressed that it would turn into a wasteful white elephant. Barely a year later, in fact, Thomas Henry Huxley had already pronounced the monumental project ‘a failure’. But when Rector Sir Patrick Linstead decided to tear the building down over half a century later, he was met with public outrage. At the time, it was reported that the decision to demolish the Institute was partly because its ‘architecture would be “difficult to reconcile” with the new science buildings’.

Among those not swayed by this line of reasoning was future Poet Laureate John Betjeman, a vocal campaigner for the preservation of iconic British architecture. Opposition to the plans grew as The Times took up the cause to save the Imperial Institute and its letters pages were filled with denouncements of our university’s expansion. One commentator writing in the Country Life magazine suggested that the Royal College of Music – in his opinion a fourth-rate building – be sacrificed in the Institute’s place.

The sad future of the Victorian edifice was almost an inevitability, as it fell prey to financial trouble almost as soon as construction finished. By 1899 it had been taken over by the government, who promptly gave the University of London half of the building for use as administrative offices; they moved out again in 1936. In some ways, the Institute was the Millennium Dome of its time; it contained a cinema, laboratories, teaching facilities, conference facilities, and hosted exhibitions. But by World War Two it had fallen from glory, with the exhibition galleries ‘desolate and deserted’ and various government agencies haphazardly squatting there.

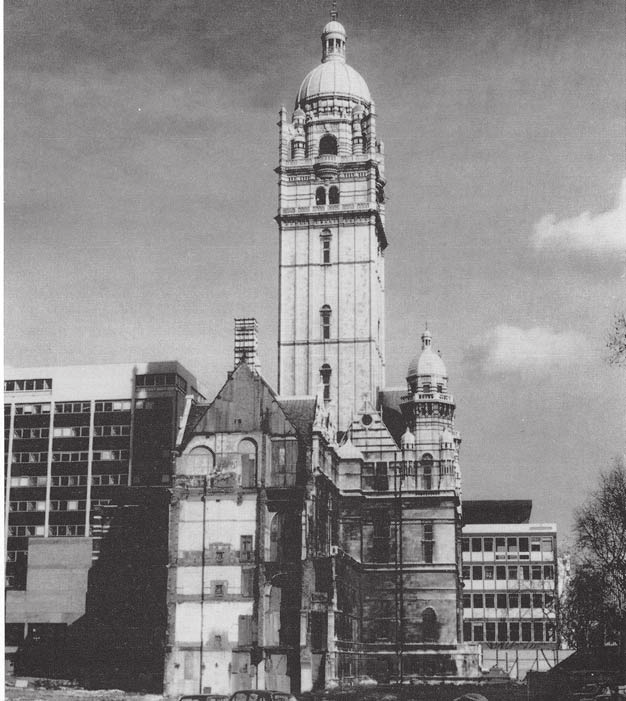

Plans for the Institute’s demolition became public knowledge in 1956. The ensuing debate resulted in a compromise leaving the Collcutt Tower, which is known today as the Queen’s Tower, would be retained. Not everyone was best pleased by this, with an article in The Engineer magazine declaring ‘there is no logic about the retention of a useless tower’ and wished for it to be unstable: ‘There is but one hope left. It is that upon examination the tower standing nakedly alone will prove to be unstable. We hope so! We profoundly hope so!’

The demolition began in 1957 with the destruction of the rear galleries in the east wing. In 1962 Imperial Institute Road was closed to public traffic and by 1965 all but the Queen’s Tower remained.

One man, Brigadier Arthur Fortescue of the Coldstream Guards, was so appalled by the act of vandalism that he dashed in and out of the demolition site rescuing “bits of decorative stonework”, as reported in the Evening Standard.

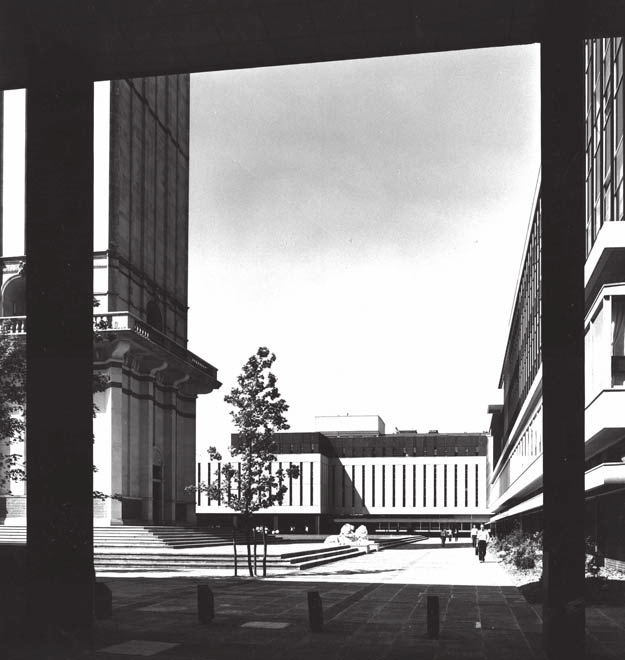

Work on the tower’s structural foundations began on the 14th of March 1966. The tower was cleaned and a new lower balcony was added. The project was finally completed in 1969, along with the ‘College Block’ development which included the Central Library building and the Great Hall.