The Tooth Fairy’s Palace

Professor Sara Rankin is asking school children around the UK to donate their baby teeth. But why?

It almost sounds like something straight from a children’s fairytale: using the milk teeth of children to build a palace. But this is no tooth-fairy-gone-rogue story, rather it’s the inventive collaboration of Imperial’s Professor Sara Rankin and artist Gina Czarnecki. The pair aim to move the debate about stem cells away from the controversies of embryonic stem cell research and to challenge perceptions about discarded body matter with a new project called ‘Palaces’.

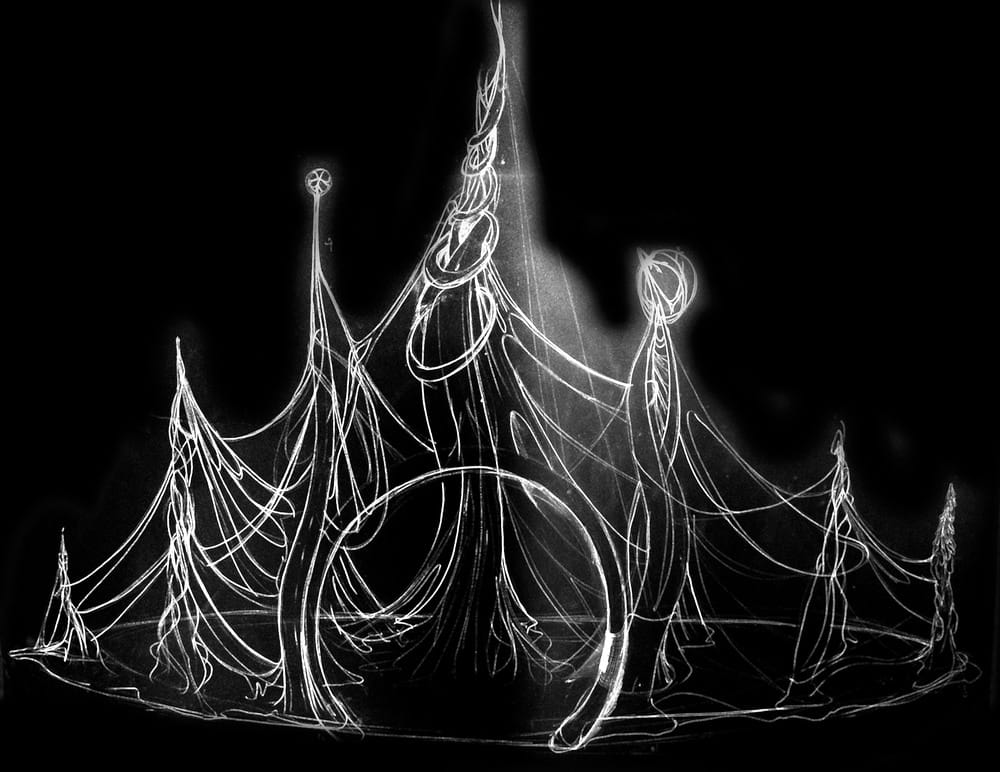

The project’s centrepiece is a 2-metre high sculpture made from crystal resin, a “spectacular fantasy palace” that will slowly be covered with children’s milk teeth. “Just as barnacles cluster in groups or in the same manner that crystals form and grow, so too will the milk teeth spread and proliferate across the surface of the palace,” says Czarnecki, explaining how the piece will grow organically over time.

Children are encouraged to send in their teeth when they fall out and are ‘compensated’ with a special ‘milk token’ that they can leave beneath their pillow as an I.O.U. for the tooth fairy. Professor Rankin jokes that her son wanted to know if she had tested the tokens to make sure that they actually worked.

One of the objectives of the project is to remind the public that the term stem cells doesn’t only refer to embryonic stem cells, but also to adult stem cells that are found in bone marrow, teeth, and even fat. “This is about moving the debate on and increasing people’s understanding. The term ‘stem cells’ get bandied around a lot because people don’t know that there are different stem cells,” says Professor Rankin.

Currently, we discard certain ‘waste’ body parts, like teeth, fat from liposuction operations and umbilical cords, when they’re actually a rich source of adult stem cells. The research that Professor Rankin is currently focused on, which involves trying to activate adult stem cells within the body instead for regenerative purposes, could see these ‘waste’ body parts becoming extremely valuable.

"This is using art, not to illustrate science, but also to catch people’s interest and to get them to ask the questions" Professor Rankin

But this is not only about making a scientific point. ‘Palaces’ has a much broader and loftier goal of encouraging interest in science. “This is using art, not to illustrate science, but also to catch people’s interest and to get them to ask the questions,” says Rankin. Outreach is a large part of her academic life. She remembers how visiting an outreach laboratory in Bristol as a teenager transformed her life and made her realise she wanted a career in science. “I had no idea that research was an option until that visit. That’s why I think it’s really important to give that opportunity to as many people as possible.”

As a PhD student she used to grab up some equipment from her lab and head over to schools where her friends were teaching and do demonstrations for the kids. As well as the general benefits of getting kids interested in science, she says, it was good for them to see a female scientist. “When you ask kids to draw a scientist, it’s always an Einstein-esque man.”

She’s keen for Imperial students to get involved as well. Both by donating their teeth – you’d be surprised how many parents keep their kids’ baby teeth, she tells me – and by going to schools and spreading the word. It’s clear that Professor Rankin feels passionate about the importance of outreach. She points out that it’s not just the children who benefit, “it actually brings a lot to your career in terms of communication skills, presentation skills, and it’s also a nice diversion from the daily grind of academia.”

‘Palaces’ has received coverage in majornews outlets and has garnered attention world-wide. It will be first exhibited in Liverpool this December, before coming to the Science Museum from April–June 2012. The plan is to travel the sculpture as much as possible so that children who have donated a tooth can come and see where it has ended up. “I love the idea that children are going to be able to give a single tooth, and then later perhaps visit the Science Museum and they can see what donating something has created,” says Professor Rankin. The hope is that the experience will encourage children to think more positively about donating in general and carry that through life.

The project currently has around 500 teeth but they’re aiming for around 12,000. The teeth so far come from all around the world, including Brazil and the USA – they’re asking people to submit their location when they submit so that they can track geographically and chronologically the growth of the project. So does Professor Rankin think it’s at all weird that they’re building a sculpture with children’s teeth? “Some people don’t like the idea and find teeth a little disgusting, but I’ve been to so many schools and all the kids love it,” she says.

If you would like to get involved by going into your old primary school and speaking to children about the project, email Professor Rankin at s.rankin@imperial.ac.uk