Ban Bland: In Defence of Popularity

Fred Fyles on populism, cultural criticism, and Kim Kardashian

Popularity. If the innumerable American coming-of-age films have taught us anything, it’s that popularity is a double-edged sword; to be popular is to be both loved and loathed in equal measure. Nowhere is this more true than in the world of music and film, where popularity often leads to an immediate critical reaction that is completely divorced from the content itself. The phrase “I liked it before it was popular” has become so ubiquitous as to enter into cliche, forming – alongside listicle, hipster, and cereal cafe – part of our post-postmodern cultural lexicon. With the internet ushering in an unprecedented era of hype, whereby acts can boom and bust in the time it takes to get through an episode of Girls, as well as a collective hive-mind insatiable in its appetite for think-pieces, our relationship with popularity is only going to become more and more complex.

I am writing in defence of popularity. In defence of the idea that something being popular and something being high quality are not mutually exclusive. Just because something is liked by many people all over the world, it doesn’t make it bad – to me this seems like a simple fact, but I have lost count of the number of times that people willingly reject certain aspects of our culture based on how present they are in our landscape. Furthermore, their attacks never form part of a critical discourse, but instead act generally as proud declarations of ignorance: ‘Beyonce’s new album? Of course I haven’t listened to it. Kanye West’s latest antics? Why should I care?’. The phrase ‘the wise man knows that he knows nothing’ may sound good, but I fear certain individuals have taken it to heart, feeling that their refusal to engage in popular culture is an admirable personal trait.

Popularity and high quality are not mutually exclusive qualities

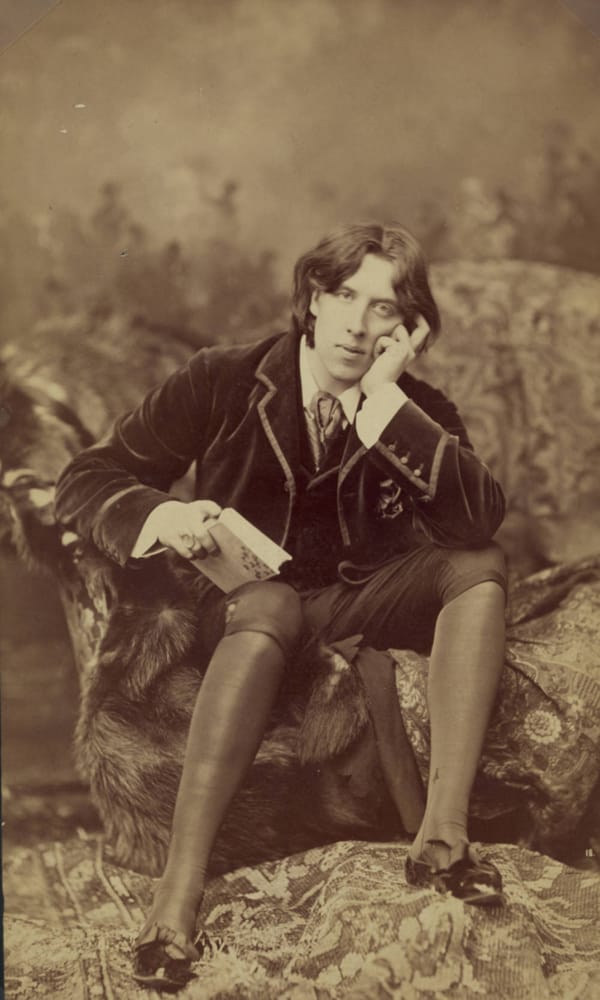

Now, I am not saying that spending all day on TMZ is a better use of someone’s time than reading Virginia Woolf, but both activities are in some way educational; your judgement just depends on how you value culture. In an ideal world I would know all about Sartre’s philosophy, the work of Marie Curie, and what happened between Solange and Jay-Z in that elevator, but this is impossible; we simply don’t have enough time, and knowing everything is an impossibility. However, it is one thing to recognise this fact, and quite another to actively enjoy not knowing something, willingly refuse to be clued-in. They are people who believe that it’s impossible to love both Martin Heidegger and Made In Chelsea, Taylor Swift and Thelonious Monk; in our post-internet age, where a wealth of culture is available at our fingertips, such an attitude is simply outdated.

That said, I understand such an attitude, and sympathise; it is easy to convince yourself that refusing to engage with the popular is not a character defect, but instead makes you a special snowflake. If you’re the kind of person who would rather read real books than magazines, who would prefer to be in bed watching a movie than out at the club, who shares be-bop interpretations of Meghan Trainor on Facebook with the caption “this is REAL MUSIC, take me back to the ‘50s!”, then, well, unfortunately you’re part of the problem. Looking at the past with rose-tinted spectacles, it is easy to feel that back then what was popular was also authentic: Kubrick’s films, the Great American Novel, The Beatles – these were what everyone enjoyed back then, right? Well, _The Shining _was accused of destroying all that was suspenseful in the original novel, James Agee only received acclaim for A Death in the Family following his death in 1955, and the highest selling single 1967, the same year Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club was released? ‘Release Me’ by Engelbert Humperdinck. It seems that things are no worse today than they ever were.

I feel that, having come this far, I should include an addendum: I am a massive snob. I am a cultural critic, so this is to be expected, and I am completely proud of my aversion to certain elements of modern life, a number of which correspond with what is popular. However, there is a key difference: I don’t hate things because they’re popular; I hate them because they’re populist. The difference may be subtle, but it’s there. While a piece of music, theatre, or prose achieves the title of popular simply by being enjoyed by a large number of people, something is populist if it has been specifically engineered to appeal to the widest possible number of consumers. To be populist is to devalue what art means, reducing it cynically to a mere product – a sweet pap made to appease a broad swath of the population.

I don’t hate things because they’re popular. I hate them because they’re populist

Yes, it is true that there is a crossover between what is populist and what is popular; just look as Sam Smith, who recently won four Grammy Awards for his soul-without-Soul – blandishments for the bland. However, there is a key difference, which we must recognise and appreciate. Kim Kardashian, for example, who is perhaps the closest we have to a deity of the digital age, is popular, but certainly not populist – her image may be carefully curated to generate online clicks, but it is certainly not designed to be appeasing. Her recent cover of Paper Magazine, which ‘broke the internet’ thanks to Jean-Paul Goude’s decision to cover her derriere in baby oil, was not intended to be inoffensive, but instead to generate controversy, something it surely achieved. In contrast, Kate Middleton couldn’t be further from Kim K; Middleton’s personal style, which generally consists of various outfits from Whistles and Riess, was part of what led acclaimed author Hilary Mantel to describe her as “designed by a committee and built by craftsmen, with a perfect plastic smile”. In this way, Middleton perfectly encapsulates the word populist: inoffensive, safe, and boring. It is this that we must fight against – if I am going to be a snob, then by God, I’m going to be the right kind. The only other option is boredom.