Diversity at the Oscars – how far have we come?

We take a look back through the last hundred years of the Academy Awards to see what has changed.

Before 1962, Hollywood didn’t make many films about race. This made some moviegoers unhappy. So, they put down their popcorn, picked up their picket signs and marched over to Hollywood Boulevard demanding that film studio executives increase the racial diversity of characters in their films. The executives listened and over the next few years, racially-diverse classics such as Lawrence of Arabia, To Kill a Mockingbird and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner were greenlit by film producers. Hollywood had increased the heterogeneity of characters on the big screen and so the protesters put down their picket signs and went back home.

And for a while, people were happy. But then they decided that even though Hollywood had widened the representation of different ethnic groups on the big screen, they often portrayed these groups in an unfavourable light. So, in the early 1970s, they once again decided to take their anger to the streets of Hollywood. One of the activists at this time was Marlon Brando – regularly regarded as one of the greatest actors of the 20th century and particularly famous for his portrayal of Vito Corleone in The Godfather (1972). Having just won an Academy Award for his performance in the film, Brando declined to accept his prize “owing to the poor treatment of Native Americans in the film industry”. Instead, the Native American activist, Sacheen Littlefeather, who represented Brando at the awards ceremony, used the opportunity to deliver a fiery rebuke of the Academy of Motion Pictures and Arts.

“Hollywood didn’t make many films about race. This made some moviegoers unhappy”

That speech was not an isolated event, it sparked a wave of diversity protests that have been troubling the Hollywood elite ever since. Much of the criticism regarding the portrayal of non-white characters in Hollywood productions began to centre around the concept of the “white-saviour” film – a cinematic trope in which a white protagonist is portrayed as a messianic figure who attains moral enlightenment after sacrificing a comfortable livelihood in order to (physically or morally) rescue characters of colour. Despite the protests, the white-saviour narrative gained popularity amongst audiences. The film that kicked-off the genre was the 1962 cinematic adaptation of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird – a story where a white lawyer unsuccessfully defends unfairly accused black clients but nonetheless, receives praise for his efforts. Even though the film was successful, it was only until the late 1980s and early 1990s that the genre really took off. During this period, white-saviour stories were released frequently enough for almost every film in the genre to be recognized as an instance of a more specific narrative. There was the story about the white coach that leads inner-city sports teams to championship success (Wildcats [1986] Sunset Park [1996], Glory Road [2006]); the story about a white teacher that sacrifices a comfortable life in order to educate underprivileged non-white students (The Principal [1987], Dangerous Minds [1995], Finding Forrester [2000]); the story about white adventurers that rescue a benevolent society from hostile invaders (Dances with Wolves [1990], Gran Torino [2008], Avatar [2009]); and in homage to Harper Lee’s epic, the story about the white lawyer that defends unjustly accused African-Americans (A Time To Kill [1996], Amistad [1997]).

Not all these films succeeded, but the ones that did were often branded by film critics as earnest attempts to start a conversation on race in an industry that throughout its history, had failed to capture the real-life experiences of non-white communities in the United States. Nonetheless, a few critics contended that while such films did succeed in crafting more racially-diverse landscapes, they often did so at the expense of the very characters that they were meant to be about. The claim is that by depicting non-whites as dependent on whites, such films only reinforce the preconceived bias that non-white characters cannot be the agents of their own destiny. To give an example, in her review of the Academy Award-winning film, The Blind Side (2009), in which a white woman rescues a black teenager from an impoverished childhood and supports him throughout his high school and college years, Melissa Anderson, former senior film critic at The Village Voice, stated that “the movie peddles the most insidious kind of racism, one in which whiteys are virtuous saviours, coming to the rescue of African-Americans who become superfluous in narratives that are supposed to be about them.”

“The Academy – largely, white old men in their 60s – had weathered this type of storm before”

That view seems to have become more popular over time, so much so that it is now the norm amongst the liberal intelligentsia of Hollywood. This being the case, the white-saviour genre seems to be slowly going out of fashion in favour of films that portray people of colour as their own heroes – for instance, in Ava DuVernay’s Selma (2014), Theodore Melfi’s Hidden Figures (2016) and Marvel’s upcoming feature, Black Panther (2018).

Indeed, the backlash against white-saviour movies has been so intense that even the seemingly innocuous musicals, La La Land (2016) and The Greatest Showman (2017) have been accused of belonging to the genre. Last year, La La Land was the early front-runner in the race for the Best Picture Oscar at the 89th Academy Awards, but after a few critics lamented the lack of African-Americans in a film that sees a white man save jazz, the movie quickly lost momentum and eventually, the race.

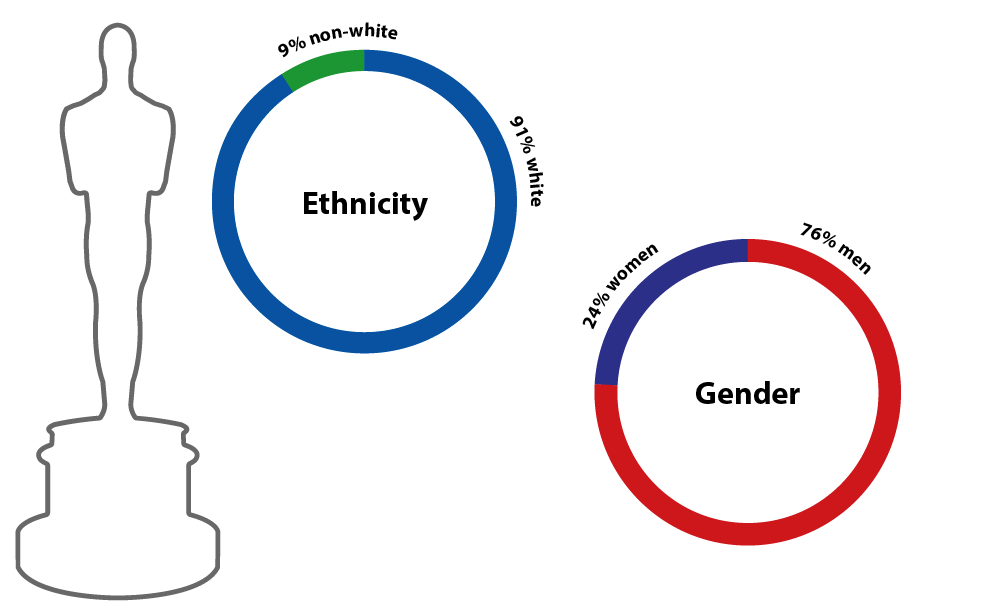

Instead, Moonlight (2017) became the first film with an all-black cast to win Best Picture; and even more notably, the ceremony had the most black winners of any Academy Awards, ever. That is partly a result of the fact that over the previous two years, the Academy had come under a new wave of more intense scrutiny for the lack of racial diversity among the nominees in major categories. It wasn’t something new to them; the Academy – largely, white old men in their 60s – had weathered this type of storm before.

But unlike previous waves, this time, the younger, conventionally successful, yet disenfranchised Hollywood actors and directors leading the charge had armies of Twitter followers behind them to champion their cause. As soon as the nominations for the 87th and 88th Academy Awards were announced, hashtags like #OscarsSoWhite and #WhiteOscars began making rounds amongst the keyboard activists of the Twitterverse. Though, going by the triumph of Moonlight at the last year’s awards, it appears that this brand of crowdsourced criticism has left a mark.

Certainly, there is nothing wrong with having a more diverse pool of nominees at the Oscars, but if that comes at the expense of artistically superior films, then in a way, it is a loss for the art of film altogether. In such a world, the Oscars are reduced to nothing more than a game of identity politics that ignores artistic masterpieces and instead rewards the most vocal identitarian movements. Take, for example, the newly-minted hashtag #LatinosLeftOut. The hashtag, coined in response to the lack of Hispanic film-makers among the recently announced Oscar nominees, is yet another example of how representation-through-Oscar-nomination is damaging the future of film. By shaping the entire conversation on film industry diversity around the metric of Oscar success, the Hollywood elite have constructed a zero-sum game that is trapping them in a vortex of never-ending diversity protests. For a black actor to win, a Hispanic one must lose; for a female director to win, a male one must lose, for a thematically-familiar film to succeed, a more contemporary one may have to fail. It’s getting to a point where future awards nomination processes may depend more on activism against under-representation than the artistic merits of a film.

When Ava DuVernay’s Selma missed out on Best Picture at the 87th Academy Awards and F. Gary Gray’s Straight Outta Compton wasn’t nominated for the same prize the following year, several liberal media outlets castigated the Academy for ignoring black actors. However, the problem with such an assessment is that it appears to fly in the face of the numbers. African-Americans constitute 12.6% of the U.S. population and since 2000, 10% of Oscar nominations have gone black actors. Assuming that most black actors in Hollywood are indeed, African-Americans, then it appears that black actors are not really being ignored by the Academy.

“The Oscars seem to be overly concerned with whether a film director is black or white, female or male, Asian or Hispanic, young or old”

The media pundits protesting under-representation of different groups at the Oscars seem to be overly concerned with whether a film director is black or white, female or male, Asian or Hispanic, young or old. An artistic purist would say that such factors shouldn’t have much to do with a film’s chances of Oscar success. Ava DuVernay’s omission in the Best Director category at the 87th Awards should not be viewed through the lens of whether the academy ignored her because she is black and female but should instead be recognized as a unique instance of a good film-maker that was not awarded the recognition she deserved. Not unlike several other actors, screenwriters, and directors that have been snubbed by the Academy after producing outstanding work. And this leads to my last point. There is no industry on the face of the Earth that celebrates itself as much as Hollywood. Awards season typically kicks off around November with the Gotham awards and then drags on for a further three months, culminating with the Oscars at the end of February. Between those two events, the eventual Best Picture winner can expect to acquire well over a hundred nominations at major and semi-major awards ceremonies, winning roughly half of them.

But what is it about such films that make them worthy of that coveted prize of Best Picture? What magic lies between those opening and closing credits that is strong enough to draw the universal admiration of the academy? Well, almost by definition, artworks do not lend themselves to objective assessment; everybody will have their own unique opinion regarding the best films of the year and those differences in opinion are likely to result in some heated argument among film critics, professional film-makers and media pundits, alike. Some will praise the summer staple of superhero-heavy blockbusters, others will brand them infantile garbage; some will sing the praises of avant-garde novelties, others will dismiss them as fashionable nonsense – there is rarely consensus in art. Even as I write this piece, there are about four films that still have a realistic shot at this year’s Best Picture prize, so perhaps the best way of determining whether a film is Oscar-worthy, is to simply try to make the Academy more representative of the wider Hollywood film industry. Once that’s done, let the chips fall where they may.