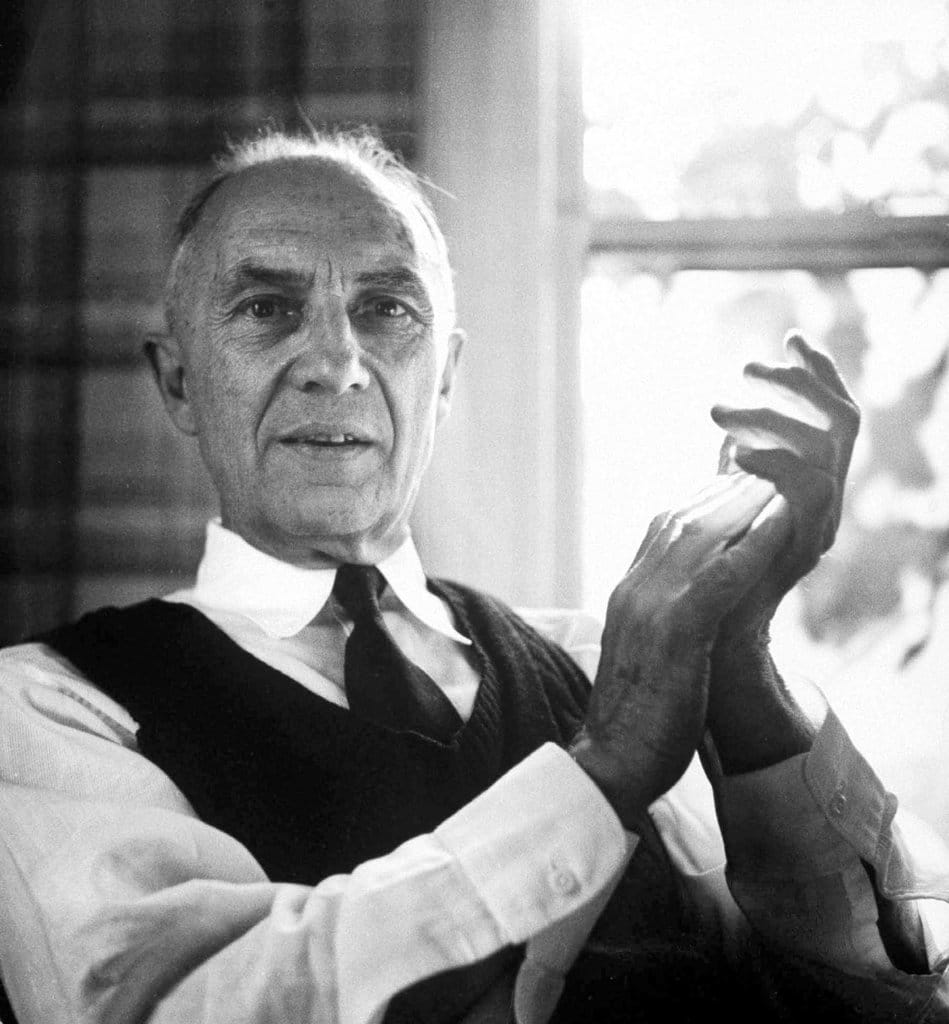

William Carlos Williams: poet, doctor, writer

Books Writer Claire Chan reviews William Carlos Williams’s doctor-themed short story collection The Doctor Stories – stories full of astute observations of human nature.

Family doctor, poet, novelist, playwright and occasional translator – William Carlos Williams wore many hats in his life as both a man of medicine and a man of letters. There seems to be a strange compulsion amongst doctors to write, as though their creative energies need some outlet which medicine does not adequately fulfil.

Anton Chekhov is perhaps the best-known example; indeed, in history, his fame as a writer has quite eclipsed his career as a doctor. Equally, Williams is perhaps best remembered for his epic poem Paterson or for his short Imagist poems such as The Red Wheelbarrow. It is easy to forget that he also had an eye-poppingly busy life as a doctor working among the poor and disenfranchised in northern New Jersey. He would work during the day and write at night, scribbling down images and bits of verse as they occurred to him alongside patients’ clinical notes. For him, “the one (medicine) nourish[ed] the other (writing)”. “[Medicine] was,” he wrote, “my very food and drink, the very thing that made it possible for me to write.”

The Doctor Stories is a selection of precisely those of his works that draw most upon his experiences as a doctor. As Williams wrote in his essay ‘The Practice’ (part of his autobiography), the relationship between physician and patient is an extraordinary one. Each individual patient, from the highest to the lowest, at some point “exhibits himself” to the doctor, seeking advice. The doctor is thus privy to, and is able to reveal, the “inner secrets” of their “most private moments”. What a parade, what a spectacle of life passes before the gaze of a doctor! Birth and death, illness and convalescence; the great and small tragedies and triumphs of life are all put on display.

Witnessing all of this, the doctor-writer is able to catch a glimpse of the “underground stream” – the hidden thoughts, motivations and emotions that are the foundation of a person’s very existence. It is these flashes of insight, these little windows into the human condition, that Williams recognised in his day-to-day work and sought to record in his writing.

Northern New Jersey was not a glamorous place to work, and the characters and situations in Williams’s stories reflect the environs of his medical practice. In The Girl With A Pimply Face, a doctor treats a poor family, even admiring the straight-talking frankness of the young daughter, only to be told later by a colleague that they are “slick operators” and “a crew of bad actors’’who are out to prey on his sympathy. Pulled from real life as they are, these vignettes sometimes have unexpected conclusions. In Comedy Entombed: 1930, the “comedy” is that a miscarriage, rather than being a sombre and tragic occurrence, is treated with incongruous light-heartedness and levity by all involved – except for the father, who alone seems to be affected by the gravity of the event.

The lens is by no means focused solely on the patient. Williams’s short stories reveal the perspective of the doctor, who, rather than a detached and omnipresent observer, is as much involved in each encounter as the patients themselves, with thoughts and feelings that are often controversial or inappropriate.

The Use of Force, for instance, describes the satisfaction, or even animalistic pleasure, felt by the doctor on forcibly prising open the mouth of a defiant child to reveal the signs of throat diphtheria. Old Doc Rivers chronicles the decline of a respected doctor due to alcohol and drug abuse, and the blind trust which he still commands among his patients – occasionally with fatal consequences.

The subjectivity of the stories is brought to the fore by the use of the first person and the constant narration of the narrator’s (is it the doctor’s? The patient’s?) reactions and judgements as events unfold. Interestingly, dialogue is put down directly in the text with neither quotation marks nor attributions to specific speakers, making the reader feel as though s/he is eavesdropping on a scene which is playing out in real time.

A brief collection of Williams’s most famous medical poems is also included. A Cold Front paints a particularly vivid portrait of a patient who, burdened by eight children and expecting a ninth, is seeking an abortion. Le Médecin Malgré Lui (after Molière’s farce, The Doctor In Spite of Himself) points out the contrast between Williams’s reality and the ideal doctor who “gr[ows] a decent beard”, “cultivat[es] a look of importance” and “never think[s] anything but a white thought”.

This anthology of Williams’s works by Robert Coles brings a valuable perspective to Williams as the doctor-writer, particularly the sensitivity and empathy with which he met his patients and the wry self-awareness of his reactions to them. The foreword by Coles, a doctor who was himself taught by Williams, and the afterword by Williams’s son Williams Eric Williams provide even greater insight into the life and work of this remarkable physician ‘of rare humanity and self-knowledge’.