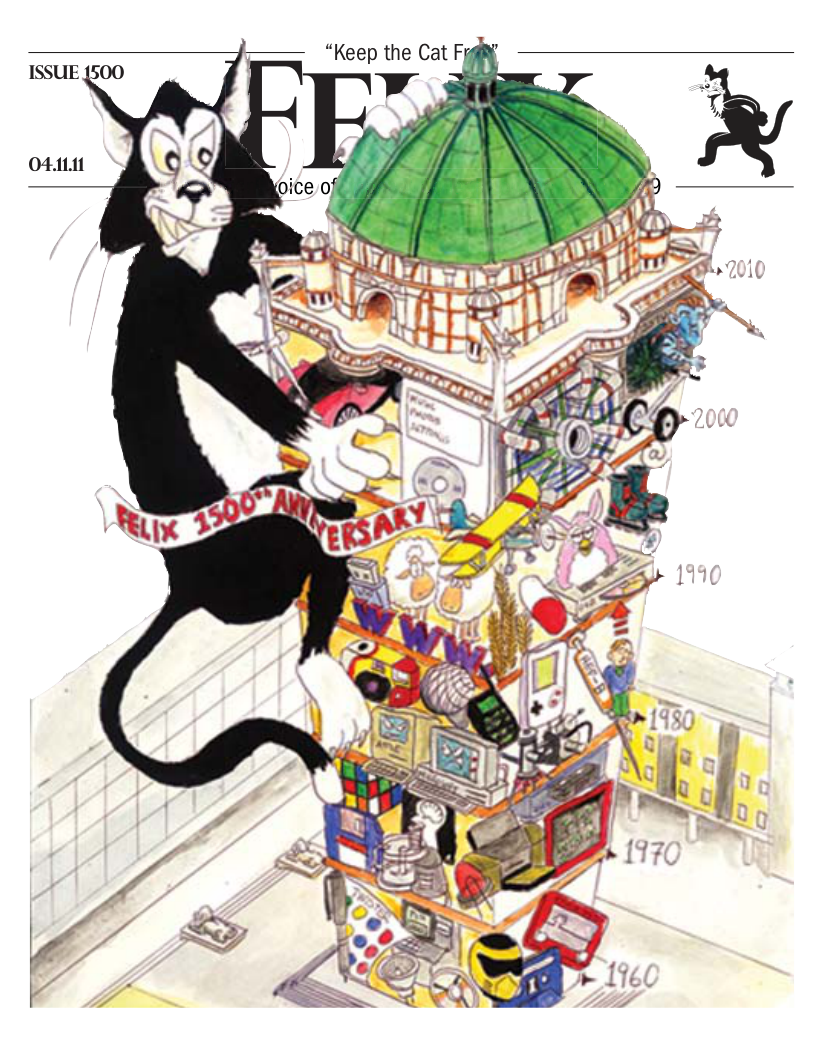

Gaming through the ages: ‘When this baby reaches 88 miles per hour...’

With a combination of persuasive power, begging and bribery we’ve managed to get together three of Gaming section’s biggest writers to talk about videogaming through the ages, as well as what they think the future holds in store when Felix 2000 rolls around...

Interested in what our writers think of the future of gaming? See the companion article here!

Felix Issue 500 (1978) - Michael Cook

It’s June 1978, and Felix is celebrating its 500th issue being printed. Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, Japanese arcades are playing host to a videogame that will become a monument in the genealogy of the medium – Space Invaders has just been released by Taito. Itself an evolution of the popular Breakout arcade machines, Space Invaders used popular sci-fi themes (the first Star Wars film had been released only a year earlier) and the combination proved a hit with players, to the point where there was a temporary shortage of 100 Yen coins in Japan shortly after its release.

In a far more muted debut, Nakamura Manufacturing Ltd. rename themselves to Namco and release their first game under the new name – Gee Bee. It receives a mixed response compared to Space Invaders, but in less than two years Namco will release Pac-Man, ensuring their place in the next three decades of the games industry.

In the US, a small group of MIT students are hard at work on one of the first interactive fiction titles ever. The first version of their game, Zork, had been finished in 1977 a year earlier, but it will take the four-man team another year to finish the game off completely. It would go on to found a huge genre (now sadly relegated to niche communities by and large) that would lead into adventure games, point-and-click puzzlers and a half-dozen more sub-genres, as well as inspiring a generation of writers and designers to work with videogames.

In terms of hardware, the revolution brought by the Atari 2600 the previous year is still the big talking point. The machine was one of the first home consoles to use microprocessors in a big way, as well as popularising the cartridge as a means to contain and sell game data. In 1978, the machine was still known as the ‘Video Computer System’ and came bundled with Atari’s Combat. It wasn’t much, but the console would become so widespread and popular that Atari would become a word describing a games console in some parts of the world for most of the next decade.

The 2600 cost $199 on release – expensive, but cheap in comparison to similar machines released before it. This was a time when 8 kilobytes of external memory was considered so extravagant that Atari limited their hardware to just half that. RAM for the entire system was just 128 bytes, mostly because of a fierce push towards small system sizes and limited resource use. But the results paid off – the console was accessible, and once Atari had established themselves with hits like Pac-Man the 2600’s position was secured.

The industry is a strange place in the late seventies. Home consoles are beginning to take centre stage from the arcade cabinets, and hardware is slowly beginning to climb the slope of affordability versus power that would lead to explosions in popularity around the time of the NES and, later, the PlayStation. In the same length of time between the launch of World of Warcraft and the present day, gaming went from consoles like the 2600 (whose hardware duplicated the left and right sides of the screen to enable simple arcade games like Pong) to the release of Super Mario Bros. in 1985. While we’ve certainly seen similar leaps in gaming since World of Warcraft (OnLive being of particular note, perhaps) the technological leaps and bounds being made in the late seventies are unimaginable to the gamers of today.

Felix Issue 1000 (1994) - Omar Hafeez-Bore

This is the most exciting annual review we’ve ever written at Felix Games! Not only are we beginning the brand-spanking-new year of 1995, but we seem to be entering into nothing short of a new era of videogame history. Both Sega and Sony have now unleashed unto Japan their state of the art CD-based consoles, whilst Nintendo is still keeping its cards close to its chest. Whether or not the Ultra 64’s software cartridges prove sturdy enough to withstand the laser-read edge of the new console CD-format is unimportant; the battle for console supremacy is going to be a spectacular show whatever the result. We wouldn’t normally bet on the newcomer Sony and its PlayStation, but the reports from Japan of Tekken’s smooth 3D graphics sound almost too good to be true. We only wish there was a way for us to see it in motion sooner.

But all this talk of the future has distracted us from the past highlights of the gaming year. Our favourite speed running blue hedgehog (as opposed to the tyre-flattened brown variety we get over here) got his second sequel and proved once again that other platform heroes are still choking on the dust of Sonic’s breakneck blockbuster gameplay. Nintendo’s star effort this year was the more sedate but no less engrossing Super Metroid, which blew us away with its atmosphere and masterful world design.

But the two Japanese giants had stiff competition from the west, with even the Macintosh computer getting a look in with an impressive debut title from Bungie called Marathon, a FPS with some interesting innovations that made Bungie one to watch. Over in Texas, id Games released the terrifying Doom II, once again turning PC screens everywhere into portals into Hell.

But Hell is a far cry from the lush green fields of England, which has proven itself a fertile ground for home-grown game developers. Chelsmford’s Sensible Software graced the Amiga with the fantastic Sensible World of Soccer, whilst over in Twycross Rare gave arcade gamers everywhere the brutal Killer Instinct, before proving itself a worthy risk for Nintendo by taking its Donkey Kong licence and producing one of the best looking games we’ve ever seen; Donkey Kong Country.

Alongside these advances there was also some loss, as Tennis for Two creator William Higinbotham passed away. His little beams of bouncing light were the first glimmers of the giant video-game industry that exists today. He couldn’t predict how important a part of entertainment history his oscilloscope experiment would prove to be, any more than we can predict the future of this new gaming era. But we’d like to think that he may look with as much wonder as we do, at how diverse and exciting gaming has become today.

Here’s to 1995 folks, and the future of our wonderful hobby.

Felix Issue 1500 (2011) – Simon Worthington

The landscape of gaming has changed a lot since the good old days of the Nintendo 64 and the original PlayStation. Gaming is more popular now than its ever been, with the concept of someone defining themself as a “gamer” becoming as superfluous as people who likes books calling themselves “readers”. Through the numerous inventions and innovations to gaming technology that pervade the current generation of consoles and games, the medium of video games has been opened up to more people than ever thought possible.

One movement that the 2000’s will probably be remembered for is the rise of the casual gamer. The start of the decade saw web games become the procrastination activity of choice for many, and the world was shocked and awed by quite how addictive virtual cricket with stickmen could be. By the end of the Noughties, with every man and his dog having a Facebook profile, it was only a matter of time before Facebook games got your mum ploughing virtual fields on her virtual farm and your gran serving virtual food in her virtual restaurant. But, like cannabis eventually leads to cocaine, casual games eventually get less and less casual until suddenly your mum is screaming down the microphone whilst playing Call of Duty. Casual games, as well as providing genuine merriment for gamers and non-gamers alike, also serve to introduce people to the medium of gaming.

Game developers are always in search of new ways of providing a fresh gaming experience, and at the bleeding edge of gaming technology lies 3D. Cinemas have been pushing 3D as the next big thing for many years, but with the advent of 3D televisions, the prospect of the technology being shoehorned into games is finally something being considered. Some games like Killzone 3 have been the first to feature 3D graphics support, and the recently released Nintendo 3DS is famously the first handheld console to support glasses-free 3D. If the new technology can really improve anything is a dubious issue, but as corporations seem insistent on persuading us to hand over more money to upgrade our kit, it looks like for the immediate future 3D is here to stay.

Another innovation that is very much in its infancy is the “gaming-as-a-service” model, which you might more readily recognise as “OnLive”. This service, which is the first of its kind to experience a mainstream release, takes the game out of your computer and onto the Internet. It’s the gaming equivalent of robotic surgery – all the keyboard buttons you press or mouse movements you make (or even analogue sticks you rotate – OnLive is available as a stand-alone console) are sent to OnLive’s servers and all you get is the video to display on screen YouTube-style. A few years ago such a concept would have been ludicrous, but with more and more homes switching to ultra-fast broadband gamers can finally experience the highest quality of graphics without needing to shell out the GDP of a small country on a water-cooled gaming leviathan. OnLive, although still to prove that it can be a success, has begun to bring big-budget titles to the impoverished masses.

The final revolution of the era has come in the form of motion control. The Wii arrived first and brought the movement-capturing WiiMote to the floor, sparking a revolution that tapped into a previously unmined seam of new gamers in the form of family gaming. The Wii was the first to really be successful in appealing to kids, young adults and parents simultaneously, and so it’s no surprise that every other games console wanted a slice of the action. Now, the market is littered with motion capture devices of questionable quality and use, but their effect of providing a much more intuitive way for gamers to control their games, hence making them much more “pick-uppable” for the casual gamer, is clear.

In moving into the current generation, games have stopped being just the domain of spotty nerds in the basement and have moved into the living room with all the cool and fashionable people. The whole concept of the casual gamer is something new with this generation, and there have been plenty of innovations that have fuelled their rise as a viable market. Now that they finally have a mainstream audience, games have been accepted as big budget entertainment – gaming is becoming, albeit slowly, as common as visiting the cinema or going to the football.