It could be worse; we could be in France

British economic cuts may pain us now, but the French failure to reform will hurt them more

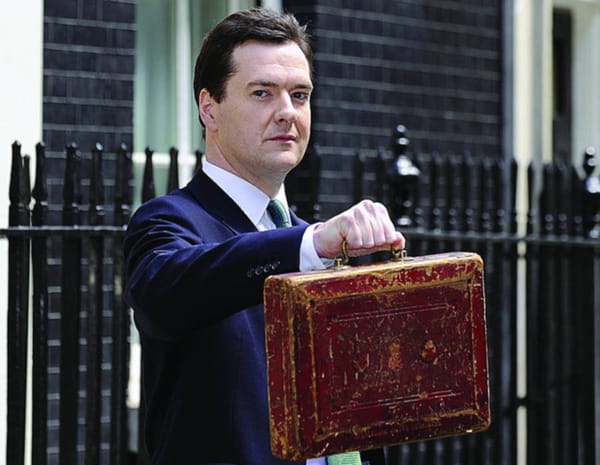

Britain’s first coalition government since the Second World War seems to be splitting at the seams as it unveils a budget to deal with the worst deficit caused by the worst recession in Britain since the Second World War. This has already caused a twenty four hour tube strike and backbench anger over broken party pledges. We can, however, at least take solace in the fact that we appear to be coping better than the other half of the entente cordial; our sister nation, France.

President Sarkozy’s plan to increase the retirement age from 60 to 62 has, to put it lightly, triggered popular discontent. The parallels with Britain, like so much of Franco-British history of the past century, are clear; a right-of-centre government bringing in major economic reform, including increasing state pension age from 65, at a time of economic crisis, triggering civil unrest. This is, however, where the similarities end. These are major protests; the sixth day of nationwide strikes and protests, each attracting about 1m to 3m to the streets, in two months has been coupled with a week-long blockade of oil refineries. The French economy, without petrol and transport, is grinding to a halt. France (or Paris, at least) has a long history of strikes bringing down governments- or at least causing embarrassing policy U-turns in the case of 1995 and 2006 reform attempts; Baron Hausmann even designed the city around protest power. France has never had a Thatcherite figure to control trade union power effectively.

The relative economic unrest should, all the same, seem surprising; Britain’s banking based economy fared worse in the financial crisis- it came out of recession six months after France (with higher decline in every quarter) and its deficit is about 11% GDP compared with France’s 7%. However, the strangest and perhaps most telling statistic is that strikers have more than 70% of popular support, yet oddly up to 70% of those polled also support pension reform. Unemployment in France has also hit a staggering 10%, and its national debt remains at over 70% – though these were recurrent problems in France before recession, which perhaps shows the big difference between the two nations.

The problem for France is not about cuts to balance the books and the discontent is not purely about pension reform. While Britain’s newly elected government deals out temporary measures to deal with urgent but short term problems, France is dealing with both economic and social problems that have been around for decades and were meant to dealt with by a president that has been in power for over three years now.

Mr Sarkozy was always likely to be a controversial radical; he showed views which, liberal or conservative, were certainly not populist. He said the French must work more and face less job security; openly complimenting the Anglo-Saxon economic model. He even went so far as to say France showed “arrogance” to not see that we were all the founders of liberty. As minister of the interior, he supported the founding of a Muslim Council in France to address their needs effectively and suggested the state should subsidise mosques to further integration yet also called Arab rioters in 2005 “traitors”. On entering office promised to create a more dynamic French economy, a more tolerant society and assert France as a power for good on the world stage (even bringing the socialist founder of Medecins sans Frontiers in as Foreign Secretary as an olive branch).

This is a far cry from what has happened. While he has reduced some union strike power and maintained the right to work long hours to maintain labour flexibility, he failed push through enough reform earlier to control unemployment effectively. When the USA and UK seemed to be bearing the brunt of world recession, he did a major U-turn and claimed French economics was right all along, making any economic reform hypocritical. The government also introduced a ban on the burqa and brought France back into NATO (an Anglo-Saxon dominated military system is anathema to many of those across the French political spectrum); both moves, regardless of national support were not policies he was voted in for. To top off his feeble attempts at political reforms, corruption charges are emerging; scandalous claims have been made over his relationship with the L’Oreal family, an icon of chic French industry.

Regardless of what we may think of the details of the cuts in Britain, the Conservatives have, by and large, showed that they have every intention of carrying out precisely what they were voted in to do. The French president, on the other hand, has spent three years alienating enough of his populace to make the desperately needed economic reform, which he was voted in for, almost impossible to push through.

These protests, it seems, are long overdue. While it is now certain that the pension reform will go through parliament regardless of the protests, the Indian Summer of Sarkozy’s presidential term is well and truly over.