Welfare for all?

Should we have universal benefits?

The middle classes throughout the developed world complain of faring worst from their governments’ budgets. They are, by definition, hard-working and economically productive. They face taxes as high as the wealthiest in their society, but find this reduces their ability to pay for relatively basic goods, such as their mortgage, rather than the ability to buy luxuries, like a Mediterranean holiday home. Despite this, they receive far fewer free or subsidised public services and benefits than the poorest in their societies.

New Labour managed to seize power from the Tories by appealing to this sense of middle class outrage; not by cutting their taxes (though they effectively promised to not directly increase these) but by giving them greater access to the spending side; benefits were introduced to help the youngest and the oldest, regardless of wealth. This included giving winter fuel allowances, eye tests, prescriptions, travel passes and television licenses to the elderly and child tax credits to families. These universal benefits remained hugely popular with the electorate and were largely unquestioned by the Conservatives, then in opposition.

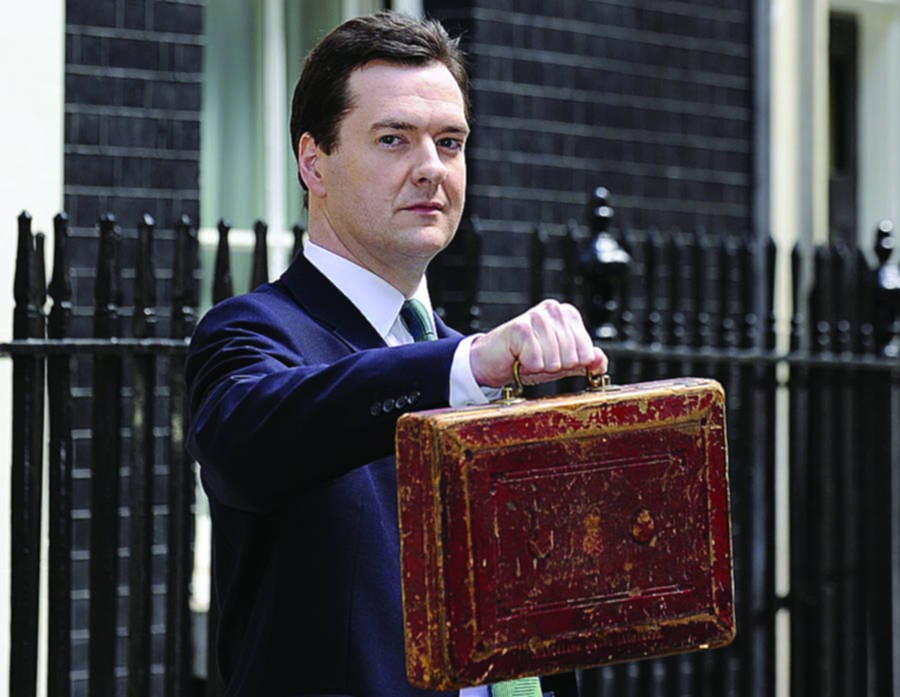

Then the need for an emergency budget emerged and this aspect of government spending suddenly came under closer scrutiny. This is hardly surprising; it is a strange yet radical quirk in our economic system that emerged to appease the political environment without any debate to justify it taking place. Now, with the buzzwords ‘necessary’ and ‘fair’ being thrown around by Government, that long overdue debate is finally taking place in Downing Street, albeit rather quietly. The debate, ideally, would also be considered at a time when tax, as well as spending, was not under considerable pressure. Nevertheless, it’s better late than never.

It was thought that this week’s emergency budget could well spell a clear end for the policy of universal benefits and a return to means testing; the result on the day was, however, rather unclear. Perks for the over 75s were, by and large, maintained with the recent increase in the winter allowance being formally confirmed and guaranteed. This is, perhaps, related to the far more important move of state pension age being lifted to 66 by 2020; finding out that retirement will come later and cost more at the same time can have a bad influence on voter psyche. Child benefits, on the other hand, have been cut for the wealthiest of families. This, admittedly, had already been openly discussed and had broad support.

The government must consider whether this aspect of government spending represents a shared universal necessity in our lives which cannot be afforded by many. In which case, like health or education, it should be universal. Otherwise, if it is considered an emergency, and almost charitable, measure for the most unfortunate in society, such as unemployment or housing benefits, which should be means tested. The distinction is rather subtle and may, admittedly, require certain assumptions about the homogeneity and expectations of society, as well as assuming that taxation and other government spending follows fixed ideologies effectively.

The government still appears to be in two minds over universal welfare; this could well be to spread the blow over subsequent budgets. We will have to wait and see if they come to a decision on its future by 2015.