Students with ‘Parasight’

The science behind the iGem team’s successful project

MIT hosts an annual undergraduate Synthetic Biology competition called iGEM (International Genetically Engineered Machine), aiming for each university team to build biological systems and operate them in living cells. Imperial made an outstanding performance and landed fourth on the podium out of a total of some 129 participating universities.

The Imperial team built their project on biosensors. Sensors developed so far require hours or weeks of waiting before a detectable output is produced, jeopardizing the product’s application on the field. Current designs also only respond to a small range of basic inputs and lack flexibility in input/output modulation.

For the detection target, the Imperial College team wanted something with a strong health impact. They envisioned a cheap, safe and fast sensor that could detect the presence of a range of human parasites in water, which would indicate to people in developing countries whether the water is safe to drink/touch – hence the project’s name “Parasight”! The IC team focused on the schistosoma parasite, a neglected tropical disease (NTD) which affects 200 million people worldwide, second only to malaria in severity.

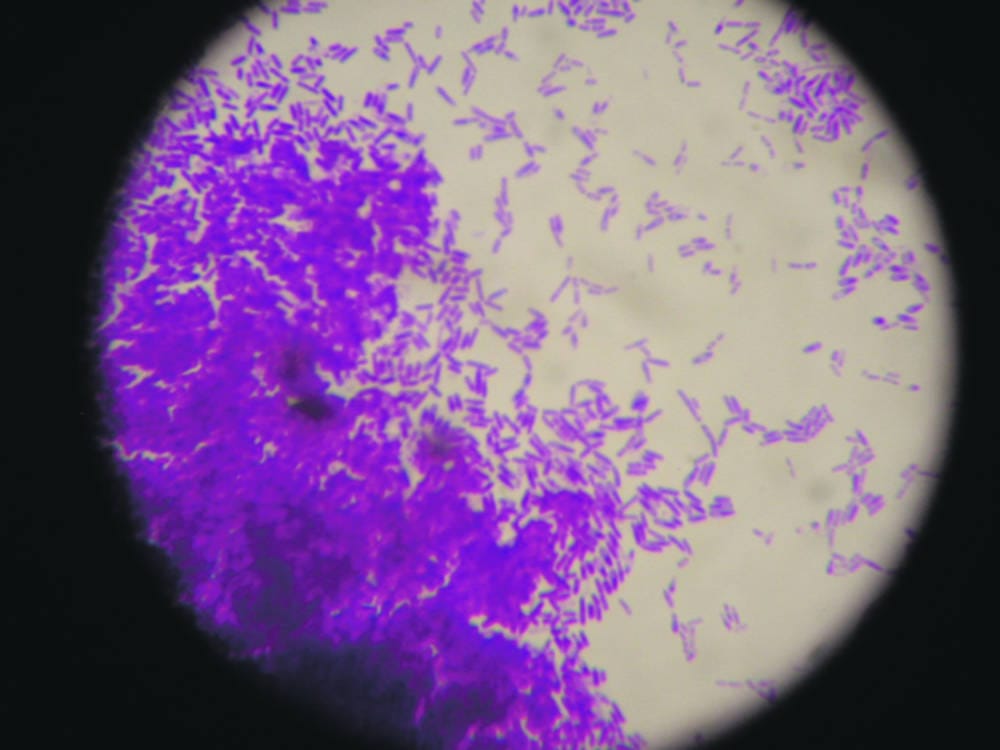

They engineered a system which allows for fast detection of a range of parasites, and may also be used as an environmental tool for mapping parasite spread. Synthetically modified Bacillus subtilis, a harmless gram positive soil bacterium, was used to give a clear colour readout upon detection of the waterborne parasites.

The team designed the project in three modules. Their detection module constitutes a brand new approach, exploiting parasite release of elastase to penetrate host skin. They synthesised a novel protein bound to B. subtilis cell surface, with a protruding signalling peptide attached via a protease cleavage site. When the parasite protease comes along, the signal peptide is released and activates the signalling module. To transduce the signal, the team used a quorum sensing system which they extracted from Streptococcus pneumoninae and transplanted into B. subtilis. Activation of this classic two-component system induces gene-transcription and triggers the fast response module.

Cercaria (larval stage) is the most useful lifecycle stage of Schistosoma to target, as it would prevent the disease altogether. Cercariae are common in water, but their spatiotemporal appearance is unpredictable. With this detection method, locals or NGOs could easily check the water to see if it is infected.

The project’s design was based on the pre-infection release of elastase by cercariae, without which they would be unable to progress in their life-cycle. The cell-surface protein of B. subtilis has three components: an auto-inducing peptide (AIP), a linker peptide and a cell-wall binding protein (CWB). In order to activate signal transduction, the AIP must be cleaved, i.e. it cannot access its specific receptor if still attached to the surface protein. Cleavage by elastase releases the sequestered intercellular quorum sensing signal. It is the linker which confers specificity to the surface protein; the elastase recognises a four amino-acid sequence (SWPL) included in the linker. The latter is anchored to the cell-wall by an isolated domain from the LytC protein, native to B. subtilis.

Cercariae do not readily release elastase in the water. They need to detect human lipids in ambient temperatures of around 37°C. However, cercarial elastase is a crucial protease for successful infection, and is thus guaranteed to be released assuming these conditions.

While an elastase has cleaved a protein linker, the team designed a resulting downstream signalling pathway. The so-called ‘ComCDE’ system of genes in S. pneumoniae signals via a linear AIP and uses a two-component signal transduction system. The ComC gene-product is CSP1 (competence-stimulating peptide-1) which is the system’s AIP. CSP-1 is exported out of the cell and is detected by the CWB – sensory histidine kinase ComD. The kinase then activates response regulator ComE. This transcription factor then binds to its specific target gene to induce transcription; the team synthetically set the Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease gene as target by adding a ComE binding site upstream from it.

Previous trials have been based on transcription-translation of a specific reporter molecule (e.g. GFP) which is time-consuming and might need sophisticated equipment for detection. This system is not only revolutionarily fast but it involves the expression of a protease which acts on a pre-existing pool of substrate, yielding an output signal several orders of magnitude faster.

Catechol (2,3)-dioxygenase (C23O) is the protein product of the XylE gene. It originates from Pseudomonas putida and is active as a homotetramer of C23O monomers. The enzyme naturally catalyses the conversion of a colourless substrate (catechol) into a bright yellow product (2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde) within seconds of substrate addition.

Modifying the XylE gene by fusing it to the GFP gene, they obtained GFPs fused to the N-terminus of C23O monomers. By allosteric inhibition, GFP prevents the C23O monomers from tetramerising; they hence remain inactive in the cytoplasm.

The fusion gene construct reveals the secret of the output module’s inducibility: the GFP gene is fused to the XylE gene through a protein sequence recognised and cleaved by TEV protease. Thus, when TEV is present in the cell, the GFP is cleaved off from its C23O monomer and the free monomers can tetramerise.

TEV protease is a natural viral protease. In the system, ComE transcription factors bind to their native ComCDE promoter upstream from the TEV protease gene. Since ComE is activated only when CSP1 is cleaved, TEV protease is only transcribed and translated upon detection of the Schistosoma parasite.

The TEV gene has high cleavage site specificity and a relatively low molecular weight (242 amino-acids) resulting in a relatively quick synthesis of the gene-product. TEV protease would then act upon a pre-existing pool of the inactive GFP-C23O substrate in the cell. Being relatively fast, it has a high turnover rate of substrate molecules. This is the first amplification step, making the response exponential over time instead of linear. The activated C23O is itself an enzyme with a high turnover rate, meaning that colourless catechol molecules would be converted to yellow coloured products very fast. This second amplification step makes the response hyper-exponential.

The IC team also ran a series of school workshops based on NTDs. “Bridging the gap between academics and capturing the wider public’s attention can achieve so much”, says the team. The iGEMers even developed a software toolkit that can be run autonomously and customised to the desired input. By changing the protease recognition site on the linker of the surface protein, any protease could be detected.

The team now hopes their system will come to good practical use. The biochemical reaction in itself is “in the box”; the skills and protocol are there for having it rapidly synthesised and ready to go. Now it needs to be incorporated into a clever device for use on the terrain. The team have envisioned a test-tube like reservoir with the transgenic B. subtilis colony at the bottom and a lid with a stick attached. The user would unscrew the lid and dip the stick into the water to be tested. The stick contains a foamy coat containing skin lipids which attracts cercariae in the water if present. They will release elastases, thus causing a reaction! Yellow product or not yellow product..?