Facing a Wikiflood

The memos released by Wikileaks are part of a wave of information. But what are we going to do with it? By George Wigmore

So says Bradley Manning, the US soldier working as an intelligence analyst in Baghdad.

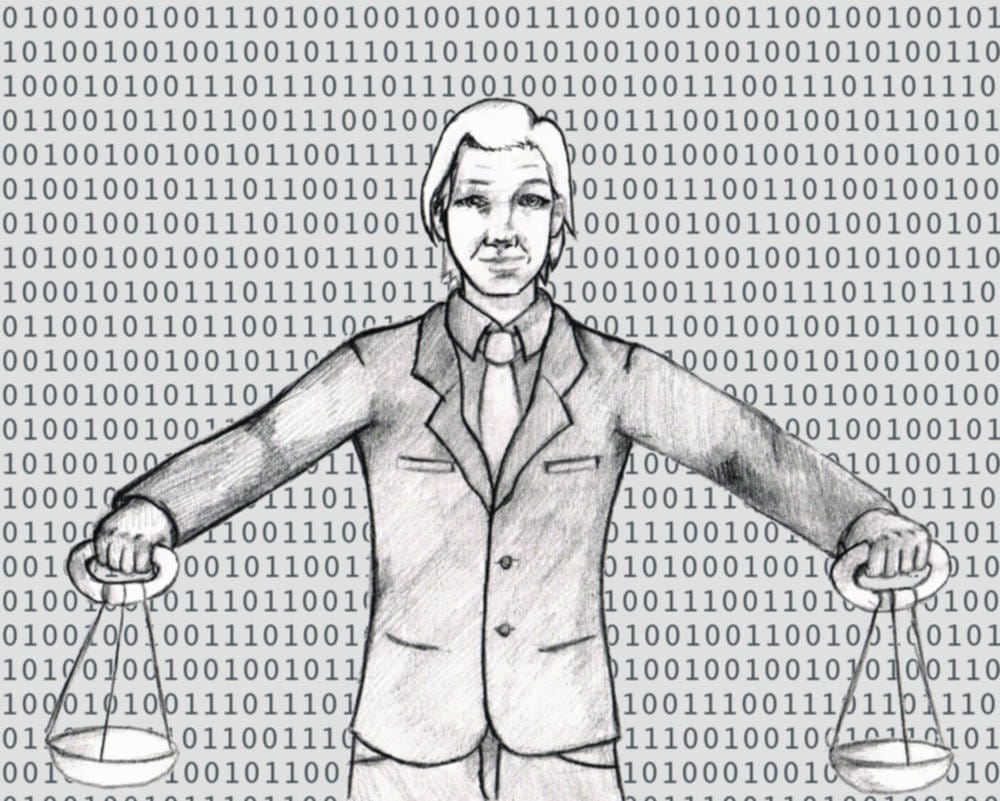

The rights and wrongs of the situation are irrelevant. The information is out there. This particular can of worms has been opened. Thanks to innovations like the internet and microchips which allow us to store huge amounts of information on a tiny memory stick, hacking into systems and disseminating information from them has never been easier. Because of this, we face a flood of information from Wikileaks.

But we also face the same onslaught from more legal means from the Freedom of Information act. Institutions are obliged to release information upon request.

Supposedly this access to previously classified information acts as a democratic leveller. Any public institution faces having its authority undermined by leaks of information which might discredit their members or shed a less than flattering light on their practises.

So if these leaks are inevitable for all walks of life, should they be filtered? The original leaked memos are all available on the internet, but how many people have actually read them? Most of us will have gained what information we have about the contents through the newspapers. We only hear about the things they choose to tell us, and only get the spin they choose to put on it.

The problem with reading these documents, is that both journalists and the general public are often poorly equipped to understand the linguistic nuances present, and in addition these documents are being viewed out of context, and not in terms of the background from which they arose. A main point of controversy about the recent leaks was Hilary Clinton asking diplomats to monitor UN officials, but, it has been argued that these instructions are not meant literally, and that diplomats would know the difference. As a Science Communication student, this reminded me of the issues around science reporting that we confront daily.

When covering science stories, journalists are faced with jargon and language, which is meaningful to the experts using it, but to a non-specialist, is easily misinterpreted.

One recent example would be one of the emails pounced upon by the right-wing press in the aftermath of the University of East Anglia ‘climategate’ email fiasco, which, like the wikileaks of recent days, involved technological foul play, and leaking of emails between researchers. Several groups maintained that these emails manifested genuine evidence of scientific malpractice, basing their claims around one email which referred to ‘Mike’s Nature trick’. While we often think of a ‘trick’ being devious or subversive, in fact this trick was simply a statistical technique used by Mike Hulme, director of the Tyndall centre for climate research, to unify two different data sets.

The link here is that leaks have revealed how the scientific and the diplomatic worlds function. The degree of secrecy and separation that existed between the public and these institutions gave them authority, but a peek into their inner workings make them seem grubby and corrupt.

Perhaps if they were a bit more open to begin with, the issues of leaks wouldn’t exist, and we might respect their openness. Perhaps. But we probably wouldn’t have as much faith in their competence. Either way, I have more faith in the institutions the leaks are coming from than the journalists who are interpreting them.

The likelihood is that we face an information arms race, as the US shuts down access to lower levels, and implements more and more sophisticated firewalls and anti-hacking devices. But there will always be disgruntled employees all the way up who are willing to leak information, and there will always be someone capable of hacking these systems. So if this leaking of information is inevitable, is an honest approach a better one, as it relies less on media spin?

Information should be free, and it does belong in the public domain. But that means we have to be extra careful with how we interpret it. It may seem that the papers are just laying open the truth to the public, but just by selecting which information to report, journalists, whether meaning to or not, will always report with a certain bias.

These wikileaks are turning into a wikiflood. How we direct the flow of information is up to us.