Privacy paradigm shift leaves Facebookers open

Feroz Salam investigates whether you can really trust Facebook

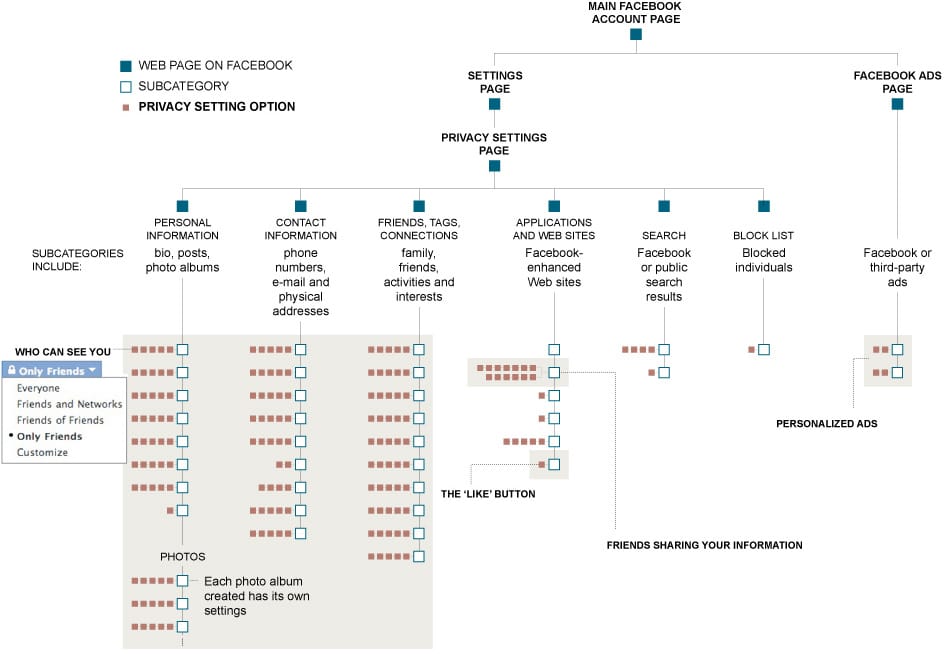

On May 12th, the New York Times published an infographic (right) that would have looked more at home in a science textbook - their breakdown of Facebook's privacy options. The final count reached 50 settings containing 170 options in total, ranging from those related to the public availability of your status updates to those about who gets to see what you “Like” and who doesn't. Facebook's privacy policy is currently longer than the United States constitution, and has grown a massive 480% in the last five years. Making sense of the tangle of options and jargon is practically impossible, and unfortunately it seems like Facebook might be banking on this to sell your information for a profit.

When Facebook was in its infancy, a social network run only for college students at Harvard, the cost of maintaining a largely text and photograph based service would have been relatively low. At its current state as the primary social network for roughly 400 million people across the globe, serving huge amounts of video, flash-based games like Farmville and high resolution images, the cost of maintaining the site must be enormous, and that gives rise to the question of monetization.

Websites like Google have an easy and obvious source of revenue with advertising based on searches. Facebook also looked to use revenue from searches, and they had a trump card, vast amounts of your personal information. Yet the problem with sharing personal data with third parties has always been, how much is too much. While I'm fine with Google picking keywords out of my emails to give me targeted adverts, would I be fine with my pictures being used to advertise an app I use on Facebook? Not so much. It's a problem that Facebook has had to grapple with continuously as they have tried to monetize their service; trying to find the line, which crossed, leads to users no longer feeling comfortable using the site.

Facebook's attitude towards finding this proverbial line has made the problem many times worse than it should be. Over half a year ago, Facebook made a change to its Terms of Service without making it clear to users. One of the new paragraphs added stated, in short, “your stuff is our stuff”. Everything you published on the service was owned by Facebook, indefinitely. After an initial uproar, this was quickly withdrawn, but it typifies their angle towards privacy issues: change the rules first, then wait and see if anyone notices. A few months back, Facebook made another new, more subtle change; allowing an increasing amount of information to be indexed by search engines. Three years ago, it wasn't possible to Google someone's name and find their Facebook page. Facebook pages were internal to those on Facebook. Three years on and the list of information from Facebook accessible to the wider internet is surprising: your name, photo, picture, gender, network information (and possibly even your wall posts) are available by default.

These changes to the service would be fine if Facebook clearly notified their users each time a change was made, or making the changes opt-in. Problem is time and time again they haven't, simply moving all users to the new, more open, privacy settings by default. It's a stalkers paradise but a job seekers nightmare. Even if you maintain a strict handle on your own settings, your privacy is also in the hands of people whom you are in photos with, and whose walls your write on. Safely maintaining that extended presence on the internet is practically impossible.

The concerns about Facebook's attitude towards privacy are heightened by the apparent nature of founder Mark Zuckerberg's development of the website. Before Zuckerberg even coded Facebook, he worked on a small project called Facemash, which allowed users of the website to rank students from Harvard by attractiveness. The only problem was Zuckerberg needed users on his website, and to get those users he hacked into Harvard's student database, downloading the required information to kick the website off. He then joined a team of students working on a social networking project called “ConnectU”, and then bailed to start Facebook using their ideas. Facebook paid $65m to the other members of the team after a lawsuit; an amount sizeable enough to suggest that there was some truth in the allegations that Zuckerberg stole ConnectU's ideas. And finally, a chat transcript from early in Facebook's days catches Zuckerberg calling users “dumb f**s” for uploading all their personal information onto his website. A healthy attitude for a man now in charge of 400 million user accounts.

Yet the one thing that has kept people on Facebook has been inertia. Once you have built up a friends list containing a network of hundreds of friends and family, no one is going to want to switch networks and rebuild that. Even more valuable are the pictures, videos and other content you might have saved on the website, a fact Zuckerberg is keenly aware of.

Changes to Facebook have been ruthlessly bold, with features being introduced without any beta testing and seemingly without regard to user response. The same goes for the privacy policy; no one really cares until something bad happens to them, and by then it's too late.

Even May 31st being launched as “Quit Facebook Day” hasn't raised anywhere near the amount of attention required to even make a statement to Facebook. If Zuckerberg is banking on apathy, it looks like a safe bet.