Imperial’s Dr Dexter comes under fire for ‘degrading’ exhibition

A London art gallery’s controversial exhibit has been branded “disrespectful and unacceptable”.

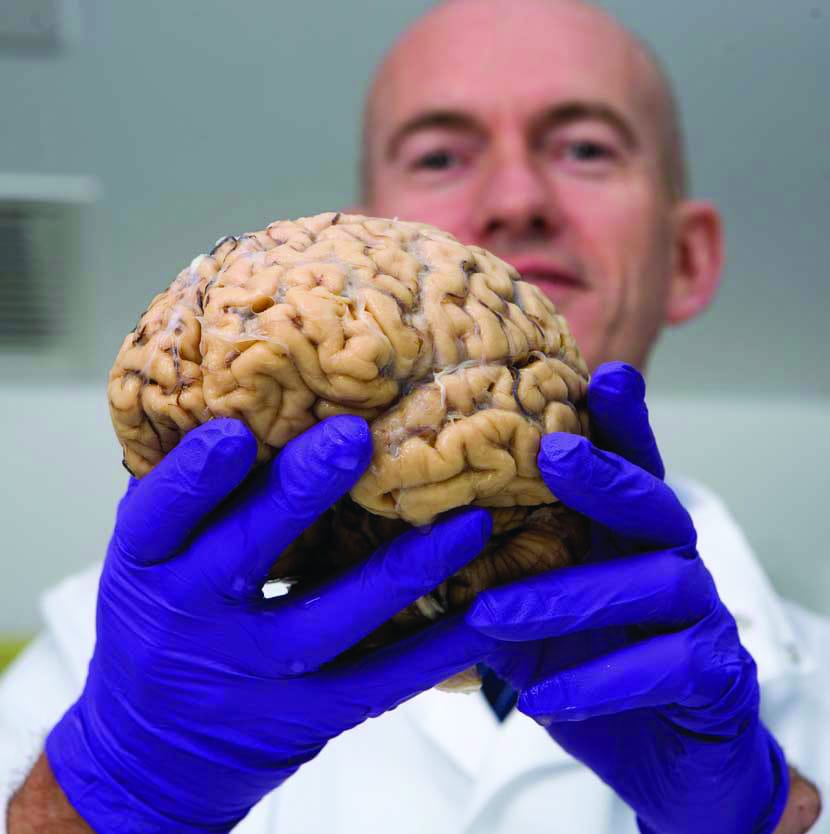

A London art gallery’s display of a brain removed from the dead body of a multiple sclerosis sufferer has been attacked by Tory MP David Amess, who has branded the display as “disrespectful and unacceptable”.

Mr Amess, a Roman Catholic and former member of the health select committee, said “it’s one thing if this is done in a laboratory, but it’s degrading to put body parts on display in a public place”.

The display, which was inspired by Dr David Dexter, reader in neuropharmacology here at Imperial College, aims to “raise public awareness of brain disorders like multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease that affect a significant number of people worldwide, and highlight the importance of brain donation for research”.

Dr Dexter responded to Amess’ criticisms last week in an article for the Guardian’s website, in which he questions whether a similar furore would have ensued if the organ on display were, say, a kidney, rather than the brain?

Dr Dexter goes on to say “you don’t go about demystifying the brain by locking it away in a laboratory, but by appropriately involving it in widely accessible media like art”. “This exhibition is a bold step in the right direction”.

Last November, Dr Dexter invited artists Katharine Dowson and David Marronto to observe a brain dissection at the Joint MS Society and Parkinson’s UK Tissue Bank, of which Dr Dexter is Scientific Director.

According to the curators of GV Art Gallery, where the exhibition, entitled Brain Storm, will be on display until tomorrow, several of the works on exhibit were made in “direct response to this experience”.

Dr Dexter is keen to stress that the brain tissue exhibited “meets the strict guidelines that govern the display of biological materials” and that the tissue “was not altered or enhanced in any way”. He feels that this is particularly important, as it means “the public is viewing exactly what the scientist has observed in the laboratory”.

GV Art is currently the only private gallery in the country to hold a Human Tissue Authority Licence for Public Display and Storage.

However, this is not the first time that the display of human tissue has caused uproar.

Gunther von Hagens’ infamous Body Worlds exhibition came under fire in 2004 when German magazine Der Spiegel reported that von Hagens had acquired corpses of executed prisoners from China.

Von Hagens later obtained an injunction against this magazine, but he was forced into making the embarrassing admission that he did not actually know the origins of the bodies, several of which he subsequently returned to China.

Then, as now, the loudest critics of the displays came from Christian and Jewish religious groups, who have criticised the display of human tissue on the grounds that such displays are “inconsistent with reverence towards the human body”.

In 2007, the Bishop of Manchester accused the Body World exhibitors of being “body snatchers” and “robbing the NHS”.

However, no such accusations can be made this time round, as the brain will be returned to the Tissue Bank at the end of the display period and its usefulness for researchers will not have been affected.

It is hoped that displaying the brain will help raises public awareness of brain disorders like multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease.

Multiple sclerosis affects roughly 1 in 700 people in the UK, while Parkinson’s affects 1 in 100 of people aged over 60 years. Both diseases remain incurable.

Researchers hoping to develop more effective treatments for these diseases are reliant on tissue donations, not only from patients affected by these diseases, but also from healthy donors. The latter are often in shorter supply but are necessary for comparison studies.

Dr Dexter believes that, as well as “pushing boundaries”, the exhibition “highlights the importance of brain donation for research”. He says: “Art has a significant role to play in science as a tool for communicating to the public what the scientist sees in the laboratory, in a form that can be understood by everyone”. Thus, it would seem that just as science and art, two cultures which have essentially been at war for the last half century following C.P. Snow’s infamous lecture, are finally collaborating peacefully together, science’s other great foe, religion, has come wading in to stir things up.

It is hard to see why Mr Amess might be so offended when they, themselves, display organs in their churches.