Slime moulds its own little landscape

A new study shows that some amoeba exhibit a primitive form of agriculture

The humble amoeba is more intelligent than you would think. A new study published in Nature by evolutionary biologists at Rice University has found that the social amoeba Dictyostellum discoideum exhibit a primitive form of agriculture.

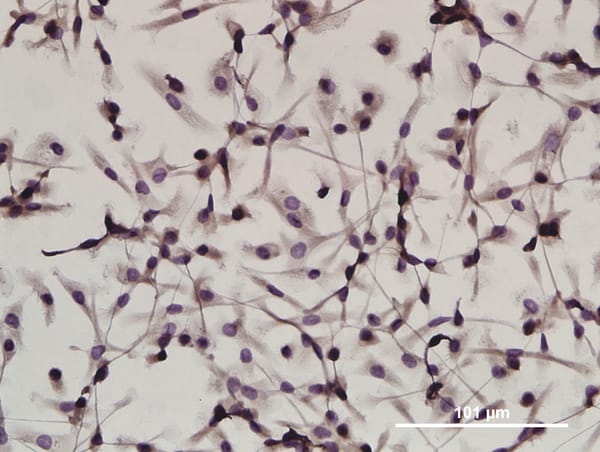

A genetic trait in one third of the “Dicty” amoeba species – also affectionately known as “slime mould” – causes them to engage in dispersal and prudent harvesting of the crop. While this form of farming may not be as advanced as that of fungus growing ants and beetles who cultivate their crops, for example, the discovery is surprising given that amoeba are mere single-celled organisms.

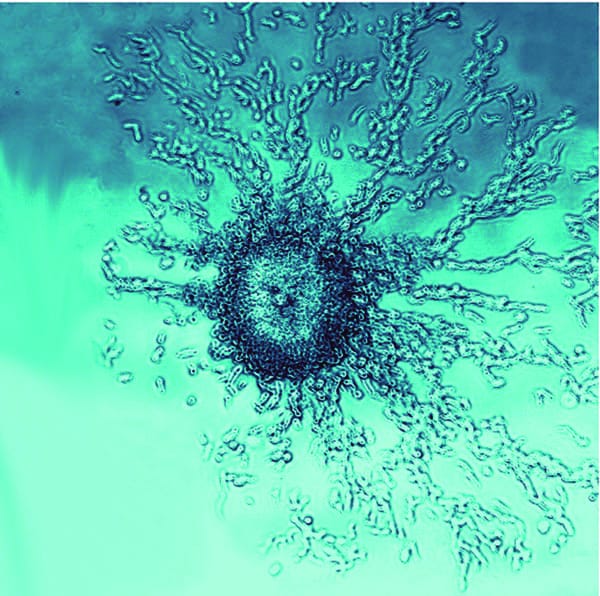

The Dictyostellum species are labelled as social since, when prey becomes scarce, tens of thousands of amoeba will aggregate into a migratory slug. If being an amoeba wasn’t already unappealing, taking part in this aggregation process is potentially sacrificial, since 20% of the cells forming the slug will die to form a sterile stalk. The stalk aids the dispersal of the surviving cells which form spores within a spherical structure called the sorus.

It was previously thought amoeba would gorge themselves on their prey, bacteria, before forming their fruiting bodies, but the study shows that approximately a third will stop feeding early and incorporate the bacteria into the fruiting bodies.

The lead author Debora Brock explains: “We think they’re able to do this because they’re social”.

Solitary amoeba, by comparison, do not form the fruiting bodies that enable the amoeba to travel.

The ability to farm is not always beneficial. The study shows that rewards of farming are context dependent. As expected, the farming amoeba had a clear upper-hand against non-farming amoeba when transferred to bacteria-free plates. This advantage disappeared when farming spores were transferred to a site abundant in edible bacteria.

The non-farming amoeba were in fact able to produce more spores in this environment compared to the farmers. The explanation was attributed to the habits of the farmers, who consume less bacteria in order to preserve some for dispersal.

A further disadvantage to the farmers is that they are forced to make smaller fruiting bodies, and cannot travel as far. “To think of a single-celled amoeba performing something that you could consider farming, I think, is surprising,” Ms Brock sai,. “choices like that are generally costly, so there has to be a pretty large benefit for it to persist in nature.”