Fort Dwarfness. Wait, what?

Dwarf Fortress: challenging, captivating, and almost completely unheard of. Keir Little sheds some light on this hidden gem

Deep underground, a lonely dwarf miner breaks into an expansive cavern. As he stumbles out into the darkness, two trolls immediately set upon him. “Bugger,” I say, pausing the game to take a sip of tea, and plan best how to save him. I order my soldiers to go down and join the fight. Meanwhile, my carpenter, desperately waiting months for the turtle shell she desires to finish her project, finally snaps. After chopping her own baby’s head off, she runs around in a rage, butchering my fort’s other inhabitants, while my soldiers are deep in the caverns fighting other threats.

There are no reloads in this game: I abandon my fort, and start again. After a few hours, goblins attack much sooner than expected. I hurry my dwarves inside to safety, but my beloved mayor is caught and killed. The other dwarves, mourning his loss, become depressed, throwing themselves off cliffs or refusing to eat until they die. I quit, get another cup of tea, and start again. I accidentally flood my fort with lava. Quit, start again. I embark upon an area so frozen, no water flows, and my dwarves dehydrate. I quit, ready to start again before I realise that I’m meant to be writing an article on Dwarf Fortress, not just playing it.

Skyrim may be ‘staggeringly ambitious’, but it’s Blackpool Tower to Dwarf Fortress’ Burj Khalifa

“Losing is fun!” is the unofficial motto of the game, and for good reason: every playthrough ends in the eventual demise of your fortress. How long you wait for that moment is a matter of experience and a lot of luck. There’s a lot that can go wrong, from the mundane (starvation, freezing, flooding) to the insane, (dragon attack, magma, murder sprees). Dwarf Fortress makes no pretence at being easy. In the indie gaming community, it’s revered: heard of by many, its influence felt in countless games (most notably Minecraft), but played only by a hardcore few.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Once you’ve got a hang of the basics, and can expect your fort to last for a reasonable length of time, DF becomes a game of opportunity, complexity and challenge. Skyrim may be “staggeringly ambitious,” but it’s Blackpool Tower compared to the Burj Khalifa heights of ambition reached by Dwarf Fortress. Recreate your greatest Minecraft city for your dwarves to live in, pump magma to the surface to boil goblins alive, arm your soldiers with steel plate, encrusted with jewels and all engraved with depictions of their victories. What you can do is near-limitless and equaling each other only in their difficulty.

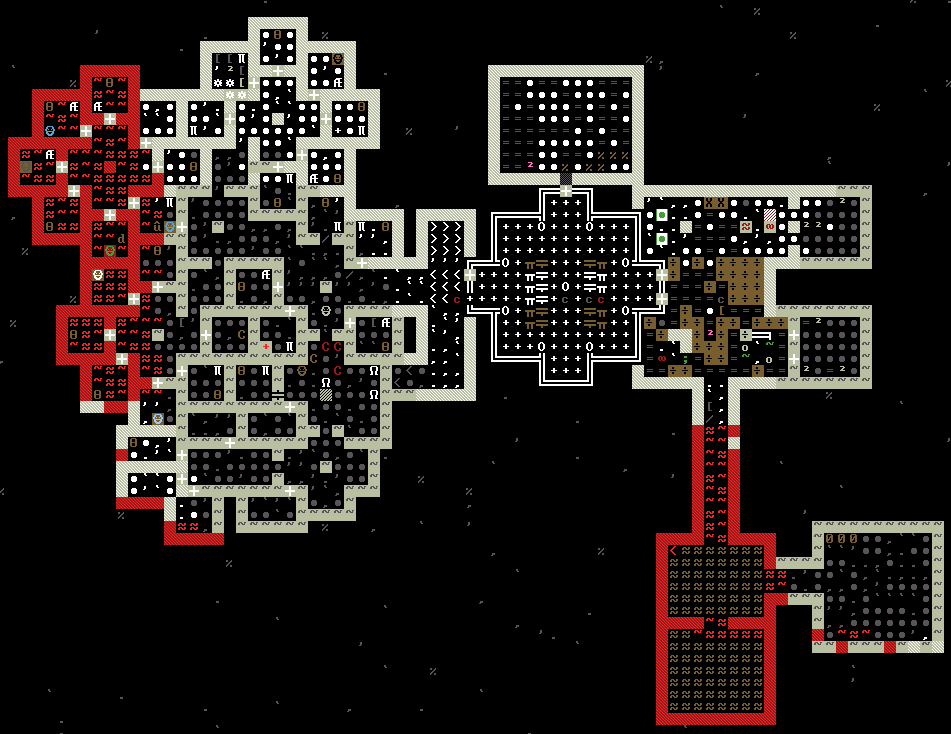

The game world is larger than you could ever hope to explore; each town has limitless random quests

Oh yes, even when things are going perfectly, this game is hard. Without graphics to hinder your imagination, you’re left with ASCII characters. Like looking at the Matrix, it’s bewildering until your mind begins to fill in the gaps. There’s no mouse control – the interface is a series of keystrokes, with the in-game menus being inconsistent and little help. Of course, it’s still in development, but the game’s sole programmer would rather work on new features than on optimisation. “The interface is coming – it's not coming in your lifetime, but it's coming,” he says. The players prefer it this way.

Having been in alpha release for over five years now, the game has built up a diehard fandom. The community is tight-knit, but welcoming, which is fortunate: without careful guidance from veterans, almost all new players would run away screaming. Most still do. The fan-made wiki is so comprehensive that even the developers refer to it, and the forums are a friendly place where noobs are encouraged to ask questions. The community are part of what makes the game such a living, evolving thing: sharing their creations, reporting bugs, suggesting and commenting on new features.

The game is the brainchild of two people: brothers Tarn and Zach Adams, more commonly known as ToadyOne and ThreeToe. Toady has a PhD in maths from Stanford, but currently works full-time programming Dwarf Fortress, living off savings and donations from grateful players. He has no current plans to charge for the game, and with its almost complete lack of graphics and notorious interface problems, it’ll never gain the mainstream attention or revenue attained by more user-friendly indie games.

Part of the reason for its difficulty is that the game, fully titled ‘Slaves to Armok: God of Blood, Chapter II: Dwarf Fortress’, shares many similarities with its predecessor, the original Slaves to Armok. Known as “roguelikes,” it and others like it were a genre of dungeon-crawling RPGs famed for having permanent character deaths, and a myrid of things which could kill or harm your character.

DF takes more than just the ASCII graphics from this genre. Its adventure mode pays homage to roguelikes, and unlike the fortress mode lets you control a single character. The game world is randomly generated; unconstrained by graphics, it details the lives of hundreds of thousands of inhabitants in text. It’s larger than you could ever hope to fully explore; each town has limitless random quests. You can even visit your abandoned dwarf fortresses, and see what foul beasts have taken over since your dwarves left. The latest version saw a revamp of the injuries system: if you’ve ever wanted a game where you can grapple and break every bone, down to each finger and toe, you should consider seeking help. In the meantime, play Dwarf Fortress! “You can't yet strangle people with their exposed guts,” Toady says, “though I suppose that's now within reach.”

Dwarf Fortress is defined by the brilliant moments that occur by chance: when your miner, set alight by the magma he just dug to, decides to get a drink from the alcohol stores, blowing up every barrel in the process; when your butcher, about to, ahem, deal with your kitten overpopulation problem, adopts them instead; when the Captain of the Guard witnesses her baby’s murder by invading elves, and vows bloody vengeance upon them. The challenge of the game becomes part of the fun: without it, these moments, greater than any scripted cutscene, wouldn’t be so satisfying.

This is a hard game, but so rewarding for those who can master it. If you’re up for the challenge, tread lightly at first: read the wiki, read the forums, watch one of the many getting started guides on YouTube. Find and read Boatmurdered, the brilliant, hilarious story of a playthrough by members of the Something Awful forums. If that doesn’t interest you, don’t worry: you’re not alone. You can go back to playing MW3 now.