Have sex, then select

Maya Kaushik on selection after copulation and ‘cryptic female choice’

Last Friday night, I was sat in my favourite bar in London with my friends, when a well-dressed young man in a suit came up to me and offered to buy me a cocktail. Pretty exciting, for a single girl, right? What this guy was subconsciously signalling to me was that he had money (at least enough for his appearance and a cocktail), and therefore probably also had good health and relatively good genes.

We’re all probably quite familiar with the theories behind courtship and mating rituals in the animal kingdom – why the peacock has such a beautiful tail, or why male cranes dance in front of females. This is the male’s way of saying to the lucky ladies “Look at me! I’m healthy and disease-free, I’ve got great genes, so let’s make babies!”

These examples of courtship are about sexual selection before mating, before any form of copulation or insemination has taken place. But what people don’t know is that, for some species, a lot of sexual selection can take place after the deed is done.

Domestic fowl, for example, are a promiscuous species, where most males get the opportunity to mate with most females, if they want to. Male fowl have developed some pretty sophisticated strategies for making sure that their sperm has the best chance of winning compared to their mates’ sperm. Sperm is a costly thing to make, so our males want to give themselves the best chance of insemination, with the smallest possible cost – the best chance of winning the ‘sperm competition’.

Researchers from the University of Sheffield found that dominant males increased the amount of sperm they ejaculated when mating with a female depending on how many partners she’d already had. If he was her first partner, he ejaculated the least… no worries there. If she’d had one previous partner, he produced more, and if she’d had three, he produced more still.

What was interesting was that subordinate males had a slightly different strategy. They increased their sperm investment up until the female had had one previous partner…if she’d had more, they let it go, and their sperm investment fell away. After all, if you’re a subordinate male, you’re not so likely to get anywhere if your girl’s had a few, more dominant partners earlier in the day.

Not only did males change their sperm investment based on the female’s promiscuity, but also depending on how attractive they found her. In fowl world, a female with a large, red comb on her head is a massive turn on. Males produced a far higher sperm investment when mating with a large-combed female than when mating with small-combed female, as well as giving the poor small-combed girls far less action.

Males also produced the highest amount of sperm the first time they mated with a particular female. After the first time, the sperm investment steadily decreased. Sort of a ‘been there, done that’ attitude – the first time is probably the most important in terms of your chance of successful fertilisation. After that, well, the novelty appears to wear off somewhat.

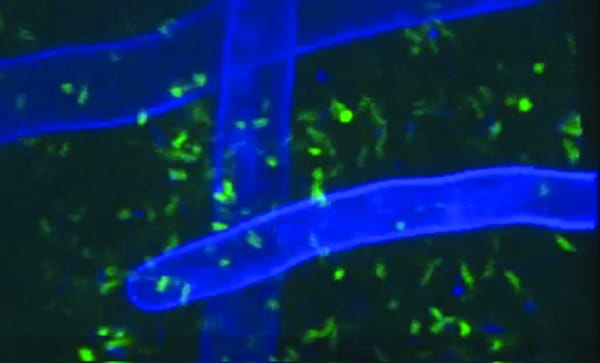

So far we’ve talked as if the guys have all the control. But there’s more at play here. It turns out that female fowl can use their reproductive tract to control, to some extent, the sperm that has the best chance of fertilisation. Female fowl were shown to expel some ejaculates immediately after insemination, and the probability of this sperm ejection went up as the social status of the male went down. Of course, it makes more sense for the female to avoid mating with low social status males at all, but unfortunately if you’re a female chicken, you don’t always have that much choice. The selection by females that takes place after insemination is called ‘cryptic female choice’ – cryptic, because this choice is hidden in the female reproductive tract, and can’t be easily seen or measured.

Sperm competition and cryptic female choice aren’t limited to fowl. There are plenty of studies showing these occurrences in a wide range of species…dung flies, fruit flies, sheep, and comb jellies, to name a few. Far less studied and harder to measure than the more obvious behavioural mating strategies, the sexual selection that occurs post-insemination may have had a far greater impact on the evolution of species than was originally thought.