A Western tragedy

Albert Nickelby turns his eyes to Europe in an attempt to explain the seismic pressures of the bond markets.

As a result of the so-called “Euro debt crisis” – whose solution seems to be too distant still to be clear – several of the euro club countries have been bailed out. Starting with Greece (2009), Ireland (2010) and Portugal (2010) have also been rescued, and in all the cases, the process followed a similar pattern.

At some point, financial analysts and the “markets” – that abstraction which so conveniently hides the fact that they are made up of people – start questioning the capacity of those countries to honour their debts. How so? Enter the credit rating agencies, whose credibility, severely harmed by the credit crunch, does not prevent them from offering their educated opinion on the subject, in the form of the rather vulgar recitation: “public debt is too high; current deficit is not being adequately tackled; hence, we are cutting their credit rating from AA– to BB+ with negative outlook…”

This brings in to question the ability of those countries to pay their debt, and panic ensues. Their public debt bonds, which are exchanged in secondary markets, become far less attractive than before, and the interest rates investors ask for buying new emissions surge. In no time, these rates have reached such high levels (about 7% interest for 10 years bonds is usually thought to be the limit) that it becomes unsustainable for those countries to sell their bonds on those terms. As a result, the credit rating agencies cut their rating further, and in no time those countries have to be bailed out by the IMF and the European Union.

As a spectator, the process seems quite dramatic. The attention of the media focuses on public finances – self-styled financial experts start pontificating about their problems, their economies scrutinised and questioned as a whole. A media circus begins, that only precipitates the outcome, and, upon being bailed out, they are forced to undertake severe budget cuts, which inevitably depress the economy further, thus forcing them to take even more radical measures that necessarily produce further recession: the tragedy has just begun.

The arguments analysts and experts usually offer are always the same. They will point out the unsustainable amount of public debt with respect to the GDP; then that their governments have failed or have not done enough to reduce their deficits; that the ongoing economic crisis means that they are less likely to grow enough to pay off their debts; that their economies have severe structural problems that make the long term sustainability of their finances impossible unless dramatic reforms are implemented. They will suggest liberalising the labour market, increasing the retirement age, VAT and other taxes, and slashing government spending: “privatisation, deregulation and liberalisation”, economists’ universal panacea.

These arguments seem sensible: offered from an expert’s perspective they are by all means good ones. However, the fallacy is that the same arguments offered to question the public finances of Greece, Portugal, Italy, Spain or Ireland can equally be used to question those of more economically fortunate countries such as the UK, Germany, France, or the USA.

The prudent finances of Germany seem no better than those of the often questioned Italy

Consider, for instance, the UK, where public debt amounts to 81% of the GDP. If the total debt is accounted for, i.e. if the foreign debt due to private individuals and companies is included, the UK’s debt is of 436% of its GDP. That is amongst the highest in the developed world: each UK citizens owes €117,580 to foreigners. Now, compare these figures with those of, say, Spain: public debt, 67% GDP; total (public+private) debt, 284% GDP; each Spaniard owing €41,366 to foreign investors. The prudent finances of Germany (83% GDP public debt; 176% GDP total debt; each German owes €50,659 abroad) seem no better than those of the often questioned Italy: 121% GDP public debt; but 163% of total foreign debt, so that each Italian would owe €32,875 to foreign investors. France has an 87% GDP public debt, a 235% GDP total debt, and each French citoyen owes €66,508 abroad.

Among the already bailed out countries, Ireland seems by far the worst case: 109% GDP public debt, and a staggering 1,093% GDP total debt, with €390,969 per capita debt: the Republic of Ireland, with 4.5 million population, owes as much money as the Kingdom of Spain, with 47 million population. Greece has 166% GDP public debt, and 252% GDP total debt, each Greek citizen owing €38,073 abroad.

Of course, the economies of Spain, Italy, Germany and the UK are not the same, which roughly explains why some are so severely questioned and others so mildly treated: it is, after all, a matter of confidence, of whether investors believe you will be able to honour your debts or not. And that confidence is more or less based on the strengths investors may see in each country’s economy. For instance, the UK has a huge financial sector and attracts and moves a great deal of capital, which accounts for much of the private debt; as long as it does not have to be bailed out by the UK government (an impossible deed, looking at the amount it owes), the UK seems to have a strong enough economy to be able to honour its debts. The huge Irish debt is also explained by the amount of foreign companies that, thanks to the Irish fiscal dumping system, have their European headquarters in the emerald isle; but as the housing bubble burst, Irish indebtedness was judged too large. In turn, Spain has suffered a devastating burst of its construction and housing bubbles, so although its public finances are by far the best of all the countries considered, its overall economic situation, with 20% unemployment rate, doesn’t seem very attractive. And Germany’s economy has fared so well during the recession, and its fame as a country that always pays its debts is so well established, that despite its public finances being no better than any others’, it is still regarded as a safe haven.

But, all in all, reasons to fear the long-term sustainability of public debt are not that well founded. Consider, for instance, Germany. It is quite true that its economy is the strongest in the eurozone, but its public debt is still an 82% GDP; its 10 public banks are close to bankruptcy, and many of its municipalities and lands are broke. A large proportion (37% and increasing) of its energy imports are Russian gas; and, most worryingly, its demographics are catastrophic: with an average retirement age of 62, in 2060, 44% of the German population will be over 65 years old. There is already a huge shortage of qualified labour, and Germany has been forced to attract engineers from all over Europe to (roughly) sustain its huge industrial sector.

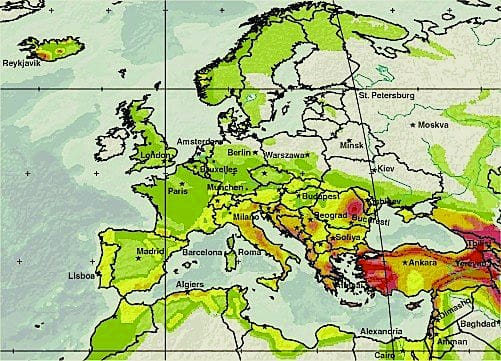

The economic perspectives of Europe do not seem buoyant

The UK is no better: apart from its huge external debt, it heavily relies on an oversized financial sector that has already been bailed out by the taxpayers and it is not, nonetheless, faring much better. Its industry having dwarfed in the last 30 years, many of its northern regions have been depopulated and underdeveloped, as the traditional industries were not replaced. There exists the increasing possibility of secession of some of its regions; and its isolationist tendencies continuously harm its national interests, as it keeps questioning the EU (while at the same time its economy heavily depends on being a member), to the point of being excluded from many negotiations where financial taxes and other decisions directly affecting the City are taken. There are no natural resources left, most of them being imported. By 2050, 25% percent of the population will be over 65, and although the UK is expected to become the most populated country in Western Europe, its social inequality, already among the highest in the developed world is, too, expected to grow.

Thus, with some countries bailed out, some others at the edge of being so, and even the most prosperous nations being objectively in not much better position, one can conclude that, in general, the economic perspectives of Europe and the Western World do not seem buoyant. Recent analyses suggest that by 2050, Europe (and that includes the UK) will have lost 50% of its wealth in relative terms. The USA’s preponderance seems to be waning, its political elites having lost their inner consensus in a situation that strikingly resembles that of the British Empire during the first half of the 20th century. The shift towards eastern Asia seems inevitable, and the current debt crisis appears to be but signalling that shift. The sad thing is that, obnubilated by our neighbour’s problems, no country in the West seems to have realised that some long-term thinking beyond the “austerity measures” might be necessary, if only so that our future can be tackled with something other than hopes of bringing the long-absent confidence fairy back.