The Bottom Billion

A review of the book and a glance at the main problem in international development

The world of international development is more often than not more complex than the image the rock concerts and heart-strings-tugging TV ads might project. Often riddled with scandalous corruption and heated debate, a heavy dose of evidence is clearly needed. Oxford Professor Paul Collier aims to provide just this in his 2007 book The Bottom Billion. Billed as an explanation as to ‘Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it’, the book injects a generous helping of evidence and statistical analysis in the aid debate, like smashing LSE and Imperial together in a particle accelerator.

A real strength of this book is that it manages to be utterly devoid of ideology. It doesn’t even argue that fighting poverty is a moral issue, rather pointing out that the practical benefits more than pay for themselves. This absence of ideology is achieved through a technique after my own scientific heart; statistical evidence. Debate around development tends to be focussed on ‘poverty traps’. The Left believe that being poor to start with keeps you poor; you can’t afford anti- malaria medicine so you get sick which means you can’t work which keeps you poor which means you can’t afford the malaria medicine next time either. All the poor need, say the Left, is one Big Push to get them onto their feet, to buy medicine for them, to educate their children etc. The Right, on the other hand, deny the very existence of such traps with all the passion of Dawkins and his New Atheists. It is aid, they say, which keeps people poor by making them dependent on handouts and putting money in the hands of unpleasant politicians.

Collier, on the other hand, sits betwixt these positions, shaking his scarily educated head. Just look at the evidence, he implores. The Bottom Billion is just that; the evidence. And having been head of development research at the World Bank and now director of the Centre for the Study of African Economies at Oxford, he’s accrued quite a bit of evidence in his time, all of which has lead him to believe that yes there are some poverty traps. But they come in different forms and may be affecting a given country in different ways. These traps are; conflict, natural resources, being landlocked and poor governance.

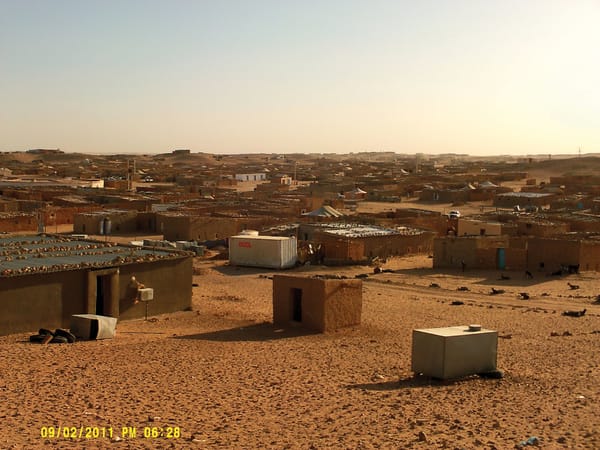

Conflict

It’s pretty obvious that a country in the midst of a civil war is not going to develop very well economically but what Collier does is to quantify this truism. From the stats, a given failing state has about a 14% chance of civil war within a 5 year period. He finds that each percentage point knocks a percentage point off that risk. So a poor country growing at 2% will have the risk of civil war reduced to 12% whereas a country declining at 2% each year will have the risk increase to 16%. Of course you might think that the prospect of peace leads to greater spending and so peace causes growth and not the other way around but even when growth is caused by a rain shock (a flood, drought of very good rainy season), the same effect is found on the risk of conflict.

This might be hard for many to accept, as it is tempting to believe that rebels are fighting for some kind of cause, not simply because of a low growth rate and besides, isn’t much of Africa’s civil strife simply a result of the horrors of colonialism? But when Collier compared countries with varying levels of economic inequality and oppression of minorities as well as whether or not they had been colonised, he could find no clear evidence that these made countries any more conflict prone.

Other than the human misery caused by civil war, the impact is economically devastating. Collier puts the economic damage due to civil war at $64 billion to both the country itself and its neighbours. Given that two civil wars on average start every year, that’s about $100 billion lost- more than the entire global aid budget.

So the poorer a country is, the more likely it is the fall into the very conflict that keeps it poor.

Natural Resources

Natural resources should be an easy route out of poverty and yet some of the world’s poorest countries have an abundance of the stuff, just think of Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Natural resources feed into the conflict trap since they provide something clearly worth fighting over, as seen in the movie Blood Diamonds set in Sierra Leone. But natural resources can damage any country because they reduce the treasury’s reliance on individual taxes, thus making politicians less accountable to their people. It is also much easier for politicians to embezzle money from natural resources and spend the money on simply bribing community leaders for their people’s votes.

What can be done?

Simply giving poor countries money is the obvious answer. But when used unwisely, aid can be counterproductive. When money flows into a country in the form of foreign currency (such as with aid) it needs to be converted into local currency to be useful. However, aid isn’t the only foreign currency that needs to become local; money generated from exporting goods also needs to be converted into local cash. So aid money actively competes with exports, reducing the value of engaging in the kind of trade which could pull the country out of poverty. Added to this, many poor countries place high tariffs on imported goods, which makes it even less likely that citizens will want to purchase foreign currency; they have nothing to buy with it, reducing the exchange value of the aid.

It also isn’t clear that aid necessarily brings growth (as argued most strongly by NYU’s William Easterly). Collier points out that a good natural experiment for an increase in aid money can be seen by the increases in the Nigerian governments revenues due to record oil prices; no additional growth followed. Not only can direct financial aid have this effect, so can the debt relief so loudly trumpeted by the Live 8 concerts. This doesn’t mean that aid is doomed to failure; rather that it can’t be seen as a magic bullet.

And aid money doesn’t necessarily go where the West might want it to go. Collier estimates that about 11% of aid is actually spent on the country’s army, representing 40% of military spending. Interestingly, Collier finds that the influx of aid increases the probability of a coup; to the victors, the spoils. Aid also reduces the need for economic reform, as it removes its urgency.

Given this, Collier’s conclusion is not that we should give up on aid, rather that it should be given when the time is right. Corrupt governments will only waste the stuff, but once a genuine reformer gets in they should received all the help they can get.

Military intervention

This is undoubtedly the most controversial section in The Bottom Billion. Remember the $64 billion lost by each civil war? Collier argues that military intervention can prove to be one of the most successful forms of aid, provided intervening forces are prepared to take real risks unlike the infamous peacekeepers in Rwanda, who would only fire when fired upon, not when civilians were at risk. The economic arguments make a novel addition to the tired (but compelling) moral ones.

Conclusion

Collier, in all, seems convinced that we can chip in. International regulation is his weapon of choice to tackle companies that pay bribes and provide a bench mark for reform minded politicians. His case for military intervention is definitely the most daring of his proposals and in a post Iraq world, the least likely to take place. Aid can make a difference when directed at the right time and at the right kind of investment (like infrastructure). The book is certainly very ‘big picture’ and a proper review of how aid works at the local level will have to wait for my rereading of Poor Economics. All in all, a worthwhile, interesting read.

And the title of the book? Perhaps the most successful criticism contained within the book is contained within that title. It is time, Collier argues, to move away from seeing a world of 1 billion rich people and 5 billion poor when so many of those poor are pulling themselves out of poverty. The Millennium Development Goals make this mistake by bunching the world’s poor together. A new development strategy focussed less on booming China, India and Brazil could achieve a lot more the poorest billion who, so far, seem stuck at the bottom rung.