The UK should adopt the Euro

Dimitri Raphaelovich argues that the UK should become part of the Eurozone

In last Wednesday’s Autumn Statement, George Osborne confirmed that the UK economy’s health was far worse than his office had expected. He blamed the ongoing Eurozone crisis of negatively affecting the UK’s economic growth, by pointing out the negative impact the former had had in our country’s exports.

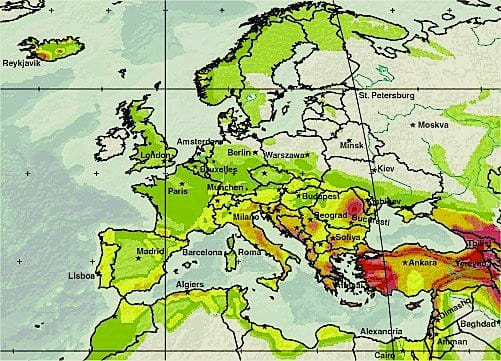

The effect of the Eurocrisis in the UK highlights that, despite having its own central bank with all the freedom to buy public bonds, to devalue the currency, etc, the UK economy is so interlinked to that of the Eurozone that all their troubles are the UK’s too. Nowadays, the UK is the eurozone’s second commercial partner both in commodities and in financial transactions; in 2009, the UK exported £103bn worth goods to the Eurozone, representing around 77% of the UK’s exports.

That is, there is no doubt that the Eurozone is the UK’s main commercial partner. And right now, like it or not, it is its position as a member of the European Union that sustains UK economy. Analysts from Foreign Policy wondered what would happen to the UK if it were to abandon the European Union and get the same commercial status as other non-EU European countries such as Switzerland have. Their conclusions were not very encouraging: the degree in which UK economy depends on that of the EU is far greater than that of Switzerland, and the commercial treaties Switzerland has are so stiff and strict that the Swiss government usually thinks of Brussels as the ‘house of pain.’ It was deemed that with the same levels of custom duties and financial transaction checks as those of Switzerland, the UK economy would not survive.

All in all, the recent eurozone events have lead to the proposal of a new financial transaction tax by some of its members and the European Commission. Aimed at “speculative transactions”, according to the EC’s proposal the tax would consist of a 0.1% tax on bond and equity transactions, and 0.01% on derivative transactions between financial firms. The money thus collected would be used to support European countries in crisis.

This tax, proposed within the framework of the Eurozone, could harm the interests of the City firms, who mostly trade in this kind of financial products. They are, as a French commentator put it, “experts in exporting financial rubbish”. Despite the protests of the Prime Minister, it seems he can do little to prevent this tax from becoming reality. After all, the Eurozone has all the right to tax whatever it wants in the same way the UK has, and if its protests are not heard it is just because it deliberately chose not to be part of the Eurozone.

However, if one considers the level of dependency the UK has with the Eurozone, and on top of that, the obvious benefits it gets out of being a EU member, it could be argued that its position as a eurozone outsider is harming the UK’s national interests. The UK should join the euro, and it should join it soon.

This might sound surprising; after all, the euro has been considered doomed many times by UK media; so was the EU in the 1992 crisis. But, as the unfolding events are showing, it was not the euro that was flawed, but the lack of a unified fiscal policy within the Eurozone. Now that the latter is heading towards a fiscal union, the euro is expected to stabilize. What comes next is a highly unified eurozone working on its own interest, excluding non-eurozone countries from decisions such as the financial tax that might affect the UK.

It could be argued that by joining the euro, the UK would lose a great deal of monetary and fiscal sovereignty. But in reality, the UK is not exerting it in essentially a different way to the European Central Bank. It is true that the Bank of England is being noticeably more flexible in buying public bonds than the European Central Bank, but the latter’s reluctance is explained by the lack of an unified fiscal discipline within the eurozone; and as Merkozy already hinted, that could change once the fiscal union is implemented. Besides, even with its “independence”, the BoE and the government have been utterly unable to prevent the UK from reaching the sorry state the UK economy is in right now: the UK is not gaining anything from having its own currency.

Hence, with such an interlinked economy, and with a fiscal and monetary policy akin to its own, not being part of the Euroclub seems pointless. By being a member, the UK’s voice would be rightfully heard in Brussels, and the economic benefits it is already extracting from being part of the EU would only be enhanced.