Why is the UK economy sinking, too?

If the Good Ship Eurozone goes down, we are going down with her, explains Albert Nickelby

The Eurozone crisis has all the traits of a perfect story: a choral drama with a fuzzy and mistrusted antihero, pompous and obscure villains, few and powerless heroes, and many victims; the plot is so twisted that its outcome remains as mysterious as exciting, and its consequences so open to chance and mishaps that any guess in this respect is but a fools errand. Hence, it comes to no surprise that the UK press devotes so much ink to the Eurozone crisis: it is where the news seem to be.

This, of course, has the intriguing consequence of neglecting domestic affairs: “the European Union could be doomed, so why would we care about the UK economy at all?” Consider this example: in 2009, as the Euro crisis unfolded, Larry Elliott, professional doomsayer and, sometimes, The Guardian’s business editor too, adopted this peculiar point of view and decided – and he has been rather consistent in this for the last two years – that the Eurozone crisis arose due to the existence of the euro alone – which the UK did not adopt, and the lack of monetary sovereignty amongst its members this implied: they cannot devalue their currencies, nor use their central banks to buy their own debt. No matter that even a 1st year economics undergrad would know that devaluating currency, buying bonds and printing money are but short-term measures that do not generate wealth (they only water it down and generate inflation), Mr Elliott concluded that it was that inflexibility that had made make the euro fail and the Eurozone break up; after all, “it is a newspaper’s duty to print the news and raise hell”. Thank goodness – Mr Elliott would say – the UK, with its own central bank, is so far away from the euro trap that none of its limitations and their consequences could affect it. Hence, it is most curious to realise that, despite all that, the UK economy is sinking as badly or even worse than that of the Euroclub. How is this possible, being outside of the euro?

Two weeks ago, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development made public its half-yearly economic outlook report and, albeit historically the credibility of its predictions has been similar to those of a drunken fortune-teller, it still offers a useful analysis of the economic health of each country. The UK’s was as bleak as Mr Elliott’s account on the issue was lukewarm: unemployment had increased, inflation was on the rise, economic growth had been almost non-existent, public indebtedness had not been halted. As an outcome, it predicted the UK economy would enter recession in this last quarter and next year’s first one. The economic growth forecast for 2012 was reduced to a mere 0.9% GDP – as opposed to the previous prediction of 2.5%. These gloomy forecasts were followed by those of Mervin King, the governor of the Bank of England (BoE), who pointed in the same direction: George Osborne, Chancellor of the Exchequer was urged to stick to his austerity measures, and the BoE to continue its quantitative easing program. Finally, last Wednesday, in his address to the House of Commons, Osborne reluctantly admitted defeat. He acknowledged that, as the economic perspectives for the UK were turning drearier than he had expected, the austerity measures would have to continue beyond this Parliament (2010-2015).

At the same time, Osborne pointed out that even though the UK government would be forced to borrow more, the UK public debt was cheaper than ever, so the borrowing costs would be lower than expected. Indeed, for three days during last week (Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday), UK public debt was cheaper than German one; on Thursday, the fickle debt markets broke the trend Osborne was apparently hoping for the next few years. Of course, the House of Commons was not satisfied with faintly optimism alone, so Osborne was force to name a culprit, which he found in the Eurozone crisis negatively affecting UK exports.

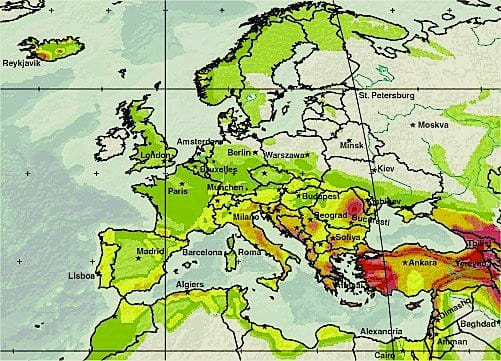

It is most ironic that such a eurosceptic as George Osborne would implicitly acknowledge that the UK economy is so dependent on that of the Eurozone that the latter can actually lead the former to recession. Indeed, the UK is the Eurozone’s second commercial partner (just behind China), and as for financial transactions, it is also its second partner (right after the USA). One wonders, this being the case, how long it would take for the UK to go bankrupt if it were to abandon the European Union altogether... But, despite this easy pun, Labour came up with a perfectly valid excuse to attack the government: it could be, after all, that the severe austerity measures Osborne has taken so far were done too soon; that Osborne’s inexperience had lead him to lift too soon the economic stimuli Gordon Brown had implemented and dramatically decrease government expenditure, thus depressing the economy. This is the stance some renowned international commentators such as Paul Krugman or Joseph Stiglitz have taken: it is not the time for tackling deficits, but for making the economy grow; rather than budget cuts, governments should develop fully expansive monetary and fiscal policies aiming at economic recovery.

It might be that both Labour and Osborne are right in their analysis, and that a combination of the austerity measures penalising consumption, and the Eurozone crisis penalising exports, is most likely a reason. But it might also be that this is not all the truth at all, nor a true cause. Chris Giles, from the Financial Times, pointed out several weeks ago that UK exports remain at the same level as they were in 2008 – before the Eurocrisis – and that, whereas in countries such as Spain exports had contributed by 6.3% towards economic growth, those of the UK had done so by only 2.5%. He concluded that the UK’s economic health was weak; the cause of it was, according to him, structural: over the last decades, as the UK industry sector underwent several crises, it appears that most of its activity did not recover. Think, for instance, of the Manchester industrial belt and how, in general, northern UK economy, traditionally reliant on industry, has not fared quite as well as that of the more service-focused southern England. According to Mr Giles, the UK economy has been remarkably bad in creating substitutes for foreign imports, even after the British pound depreciated by 20% during the crisis.

Furthermore, the crisis seems systemic. As it happened in so many other countries, at some point during the gilded 90s and 2000s, economic figures stopped reflecting reality. After a trip to London during the early 2000s, a Canadian analyst from the Toronto Star pointed out he could not understand how UK citizens could afford to live in London: their salaries were, it is true, higher than those of Canada, but the cost of living was also in proportion, extremely high. Indeed, at some point after reaganomics kicked in, salaries and pensions stopped reflecting reality: they were just not enough to pay for basic goods, not to mention luxury ones. Fortunately, credit was cheap, so consumption was kept up with debt. As Alan Greenspan and company lowered interest rates further, they fuelled the late economic bubble, which finally burst. After it burst, all that remain were heaps of debt to be repaid.

In this sense, the UK is amongst the highest debtors in the world, owing about 450% of its GDP, and with a government debt of around 85% GDP. But, despite having a deficit higher than that of Portugal, Italy, Greece or Spain, and being far more indebted, “the markets” are not attacking the UK. Why so? Osborne claims this is due to the credibility his austerity measures have given the UK. Most analysts, however, believe it is due to a complicated combination of facts. On one hand, most of the potential attackers dwell in the City of London, and some believe that “one does not pooh where he eats”. Besides, the maturity of British debt is of 13 years on average, meaning smaller refinancing needs, and the quantitative easing program seems to be buying so much UK debt anyway that markets are not seeing much of it. Furthermore, the economic growth being so low and the austerity measures so tough, it is believed that the Bank of England will not dare to raise the interest rates in the years to come. Hence, any eventual UK bankruptcy is deemed unlikely.

However, these measures have flooded the markets of the pound, and along with the slim growth, explain the pound sterling’s recent devaluation. They also account for one of the most dramatic consequences of this gambit: the UK’s huge inflation. With figures of around 5% in the last two years, Mervin King forlornly pointed out that inflation, combined with the crisis, the budget cuts and the loss of social benefits were dramatically harming UK citizen’s standards of living. Recent projections expect them to be at the same level of 2001 by 2017. This is as bad as Greece, and unprecedented in the UK; something similar in the 1970s cost Callaghan his premiership. But with the markets especially sensitive to high indebtedness, and with a stagnant economy, Osborne can only keep his cuts, and the BoE can only keep his QE and low interest rates – at least, in appearance.

Those being the structural problems of the UK – a weak industry and high indebtedness – the Tory agenda seems to have miserably failed; none of its promises have been delivered, nor it seems they will; neither has the private sector overtaken the public one as the main driver of the economy (has Osborne done anything after all to enforce that?), nor do the British people live any better than they used to; the Cameron government has actually made them worse off. It could be seen as a matter of political inexperience – after all, neither Cameron nor Osborne had any before coming to power – combined with too much ideology and too little pragmatism.

For, if the reader wonders whether anything better could have been done, he can kindly turn his gaze towards Sweden, where the conservatives rule a non-Eurozone country, and by wisely combining mild budget cuts, fiscal stimuli and political discretion rather than confusingly mixing savage cuts, fiscal austerity and neo-liberalist fanaticism, they have been able to maintain their people’s standards of living.