Is Microsoft a dying firm?

In the world of Google and Apple, Rudolf Lai asks if there is a future for Microsoft

Ten years ago, Microsoft’s products were synonymous with personal computing. The Internet was just stepping into households; Apple narrowly escaped bankruptcy, and its computers were seen as luxurious goods made for designers. In a blink of an eye, Apple became the largest technology company in US by market capitalization in May 2010; in 2009, Google attracted nearly two thirds of the worldwide search volume through its search engine and its sister sites. All that Microsoft seems to be doing is to follow what everybody else has done: launching Bing after Google, releasing Windows 7 Mobile after Apple’s iOS. In fact, many people have declared that Microsoft is “dead”.

But is that the case? Microsoft’s dominance has long preceded the rise of Google and the comeback of Apple. From a multi-stage dividend discount model perspective, Microsoft should be in its stable growth period (i.e. the last stage of the model), hence it would be perceived that Microsoft is not as ‘trendy’ or ‘strongly growing’ as the other two companies. Nonetheless, the two biggest elements of Microsoft’s business, the operating system and the Office suite, still have significantly greater market share than its competitors. The Windows operating system and Office make up 53% and 42% of Microsoft’s 2010 revenues respectively. As of December 2010, Windows had about 85% share of the operating systems market, and Office has 94% market share, according to Gartner. In contrast, Google’s business is largely internet-based; around 70% of Apple’s 2010 revenue is from mobile computing products like the iPhone, iPod, and the iPad, and the rest are in its OS and Mac hardware. One could argue Google and Apple’s recent stardom is mostly based on a combination of new technologies, like faster internet connections, cloud computing, and mobile computing, and that Microsoft’s traditional playgrounds of the OS and the Office suite remains relatively unscathed.

Microsoft still has its competitive advantage in the OS and Office area, and it has entered the gaming console market, which neither Apple nor Google have access to. Undoubtedly, Apple and Google are trying their best to step into the OS and business productivity application territory. For example, from Apple we have the OSX and iOS operating systems, and the iWorks office suite; from Google we have internet-focused software like the Chrome OS, Google Mail and Google Docs. Just by the numbers, however, we can see that there is a long way to go before we can even say that there is major competition in the OS and Office markets.

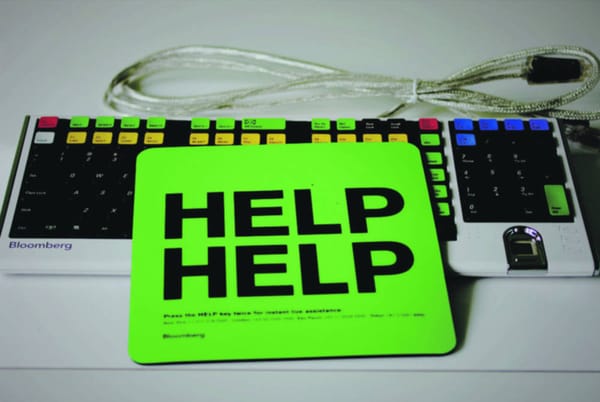

Corporations and businesses are one of Microsoft’s major sources of revenue. The prime reason for corporations to stay with Windows is Microsoft Excel. Excel’s variety of functions, and the extent of which these functions are implemented, is unparalleled in the commercial electronic spreadsheet market. Specifically, equipped with Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) and now .NET, Excel offers the possibility for programmers and developers to embed code directly into spreadsheets. Through the embedded code, a spreadsheet can offer functions that manipulate data in ways normally impossible using standard spreadsheet operations. In a way, Excel is like the Apple App store for business and finance. It provides a common platform on which software houses can develop and release applications, and the spreadsheet format is a widely understood input method. From option pricing tables, to portfolio optimization software, Excel offers an easy way to represent the input and outputs of mathematical models or other number crunching engines.

On a related note, a second reason that businesses are reluctant to change from Windows to another operating system is the cost of switching to others. Corporations have invested a lot of resources into supporting a Windows oriented infrastructure. They have hired .NET and VBA developers, and made custom applications that only run on Windows. They have trained their staff to use Excel, the Office suite, and VBA. They have virtual desktop systems devoted to delivering a Windows environment to a new computer or a new user in a matter of hours. Costs aside, there is just little reason for corporations to switch to another operating system that does not run Excel natively, and one that requires re-training staff. As such, Microsoft will continue to reap sales from new versions of Office and Windows. In 2009, a new version of Windows was released, and as of 2010 it has sold 175 million copies, making it the fastest-selling operating system in the world.

Microsoft is also strong in is the gaming market. Arguably, the iOS platform from Apple also provides a platform for gaming, but due to the nature of the hardware, the range of games cannot be considered a direct competitor to the Xbox franchise. Xbox has performed well relative to other major consoles: sales of video games and other software for the Xbox 360 topped $3 billion in 2010, topping the Nintendo Wii (at $2.6 billion) and Sony’s PlayStation 3 (at $2.1 billion), reports a NPD Group market research.

A gaming console is largely dependant on the games that are played on it. In November 2010, Microsoft released the “controller-free gaming and entertainment experience” Kinect for Xbox, which triggered a wave of new games taking advantage of the new hardware. Game/software sales for the Xbox 360 rose 29% in December 2010, compared to the same month the previous year, according to the BMO report on the NPD numbers. The introduction of Kinect puts Xbox in direct competition with the Wii in terms of using body movements for input, but the absence of a physical controller for Kinect may prove to induce a greater variety of games developed for the device in the long run.

Admittedly, under the guidance of Steve Jobs, Apple seems to be delivering hit product after hit product. Google, on the other hand, seems to be permeating every aspect of our cyber life. In the vast industry of technology, we cannot say that Microsoft has its monopoly over the business like it did. But we can attribute that change to a shift in the boundaries of the tech industry, rather than an absolute shrinkage of Microsoft’s business. With the recent uprising of what is called the ‘closed internet’ – Facebook – a network that Google has no access to, and the health concerns surrounding the Apple CEO, the scoreboard of tech giants is still undecided.