From Mirpur to the Midlands

Omar Hafeez-Bore and Kahfeel Hussain on how Pakistani immigration to the UK changed not only this country, but parts of Pakistan and Pakistanis themselves

For an international student from Pakistan, London is an explosion of new experiences. People form queues, food is bland, the police actually care (but families hardly seem to), dogs are walked, old men jog, commuters are silent, ‘smiling shop staff’ are rarely as described, and under the ground men sit and let women stand on tubes, whilst above it buses actually arrive on time. Compared to Islamabad, it might as well be Oz.

What anchor can such a student reach for in this sea of change? Perhaps the Pakistani communities who settled here years ago, who still cling on to their rocks of religion and tradition like barnacles in this cultural storm? Not quite. The Pakistanis here have changed. Many were originally from Mirpur, a land just 68 miles from the people of Islamabad, but a world away from their thoughts. A land whose people are almost unknown to the rest of Pakistan, yet make up the overwhelming majority of Pakistanis here in Britain. And because of this, it is a land whose future is now tethered to the insulated communities that have grown in England, a bond of people stronger than any international alliance or diplomatic gesture.

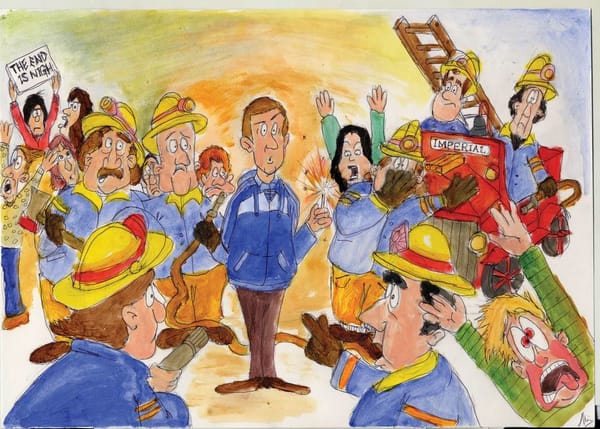

Every year another kind of Pakistani leaves home to study in London. He is a British Pakistani, brought up here but on a solid foundation of Pakistani-ness, evident in his view of punctuality as a quaint pursuit of white people and his casual mistrust of British authority. His parents came from Mirpur but his home is in those old industrial towns of the midlands and the north. He comes to Imperial College, having worked hard to come to London, the big city. It is the land of opportunity and diversity, of exciting events and important happenings.

Mirpuris, sometimes branded ‘backward’ by snootier migrants, often embody the idiosyncracies of ‘Pakistanis’ to their extreme

It is crap. People are antisocial, no one drives, proper apna food is a rarity and tasteless frauds all too common. The fashion is over-flamboyant, cricket is under-revered, no one has any community contacts and even fewer seem to have common sense. Suddenly uprooted from his community, from his Biradari, our man looks for commonality in the university’s Pakistani Society, one built, surely, upon the values by which he defines himself. One built upon his code of Pakistani honour, of izzat, of unspoken community, unbreakable pride and a nuanced love for Doner Kebabs. Instead he meets some freshies, educated Pakistanis fresh-off-the-boat from Islamabad, 68 miles from Mirpur but very different in their character.

Well, duh. A lot can happen in 68 miles. One crosses the eastern border of the Punjab into the South-West of Azad Kashmir, the less disputed part of the highly disputed Kashmir region. One leaves the middle classes of Islamabad’s airy streets for the farms and fields of the Mirpur region. The refined Urdu of newsreaders morphs into rapid fire Potahari, or ‘Mirpuri’, and the people harden from educated urbanites to the earth-wise people of the country. It makes the southern-fairy/northern-monkey divide of England pathetic by comparison.

But even those 68 miles are nothing, a few inches on a map compared to the 6,000 mile migration to Britain and the 40 years spent making it their home. That’s a real, four dimensional shift, a Back-to-the-Future style alternate reality compared to the Pakistanis who carried on back home. All geographical and class comparisons are just exaggerated by adaptations of Mirpuris in this foreign land.

So far, so human. Wholesale migrations of communities are nothing new, and it is certainly not just Mirpuris who have settled here. I could talk about the reams of Punjabi Pakistani migrants, like my mum’s own family from Gujranwala or Phelwana da shehar, the ‘City of Wrestlers’. This also explains my near-superhuman strength. Or, I could talk about the Pakistanis who settled here after fighting alongside the English during the war. Or the post-partition sense of freedom, of starting anew. I would mention those willing to work for a better life, who came during the post-war years from the newly-minted Pakistan into the open arms of an English industrial boom.

All of these settlers helped build new Pakistani villages, ones carved into the urban coves of industrial towns in Yorkshire, Lancashire and the Midlands. Ones with fewer donkeys. All of them are responsible for a strange hybrid-culture of the Pakistani and British working class, one that is both part of, and yet alien to its two parent countries. And all of them have brought up children here who embody this limbo community, not quite integrated enough into the British mainstream to stop referring to them as Johns or Gorey, but not desi enough to feel at home on the Pakistan trips of their summer holidays.

These are the children of all Pakistanis. From the hard-line religious to the hard-drinking rudeboys, the focused student with dreams of studying pharmacy or the relaxed school-leaver helping his dad in the tyre shop. All are born (at an impressive rate) in all-Pakistani migrant communities. All suffer from the cultural confusion brought about by their circumstance.

So why the Mirpuri focus? Extremism. That is to say, Mirpuris, sometimes branded ‘backward’ by snootier migrants, often embody the idiosyncracies of ‘Pakistanis’ to their extreme, as well as the effects of the last 40 years A.B. (After Boat-trip). And numbers. Mirpuris make up a huge proportion of England’s ‘Pakistani’ community. This severed limb of Pakistan has flourished, growing rapidly here in this foreign culture medium.

Calling the Mirpur region a limb of Pakistan, however, is an exaggeration. It is at best a little finger, making up just 0.13% of Pakistan’s land mass and 0.22% of the total population. This is roughly equivalent to what the Isle of Wight is to Great Britain. Okay, so more a finger nail, then, but one that has helped etch a thriving scene of markets, curry-houses and Asian fashion emporiums into the urban landscape of Britain. It is estimated that around 70% of the 800,000 Pakistanis living in England are of Mirpuri descent, and in towns like Bradford this raises to 90%. This has often made the people of Mirpur the unofficial, unintended, but undeniable ambassadors of Pakistan in the U.K. I have been brought up in Birmingham (may it forever stand tall) all my life, but still had to readjust my impression of what a Pakistani was when I met middle class and highly educated Pakistanis at university, who so differed to the desi Mirpuri-Punjabi combo of the midlands. Using my Talking-Real-English voice (full sentences, proper words, less grunts) with Pakistani peers at university is a novelty that still hasn’t got old.

But bro, how did all this happen? It can’t be denied that all the reasons for migration described earlier are important. But none of these are as dramatic as the 1967 construction of the Mangla Dam, the world’s largest earth filled dam. It was designed to increase water for irrigation and source more electrical power in Pakistan. Oh, and it also submerged around 280 villages in the region, including Old Mirpur city, displacing 110,000 people in the process. Such collateral damage could not be ignored, and Pakistan quickly brokered a deal with a welcoming UK, giving compensation, Mahfeza, to scores of men. This took the form of get-into-England-free tickets, where they could go and work in the textile mills and factories of industrial England.

Just temporarily, of course. Just a quick fortune made and then an even quicker journey back to Pakistan, right? Right? How wrong they were. England proved a more fertile land than they could ever expect and, without realising it, these men of the earth grew roots of their own.

We hope to delve into the concluding part of the story – from big gangster attitudes to the Little England of Mirpur – next week.