Tate Modern’s blockbuster Orozco

Rocío Molina Atienza asks whether this high-class freak show is more than the art of drawing crowds

Is it worth going to see another exhibition full of quirky art put there just to leave the onlooker wondering how anyone can call it ‘Art’? Beyond the bewildering first impression, Orozco’s exhibition at the Tate evokes a personal and surreal world where playfulness comes side by side with death. On entering the gallery, you can find a primaeval clay heart made simply by the artist’s hands compressing a piece of mud. It has a simple but powerful beauty to it.

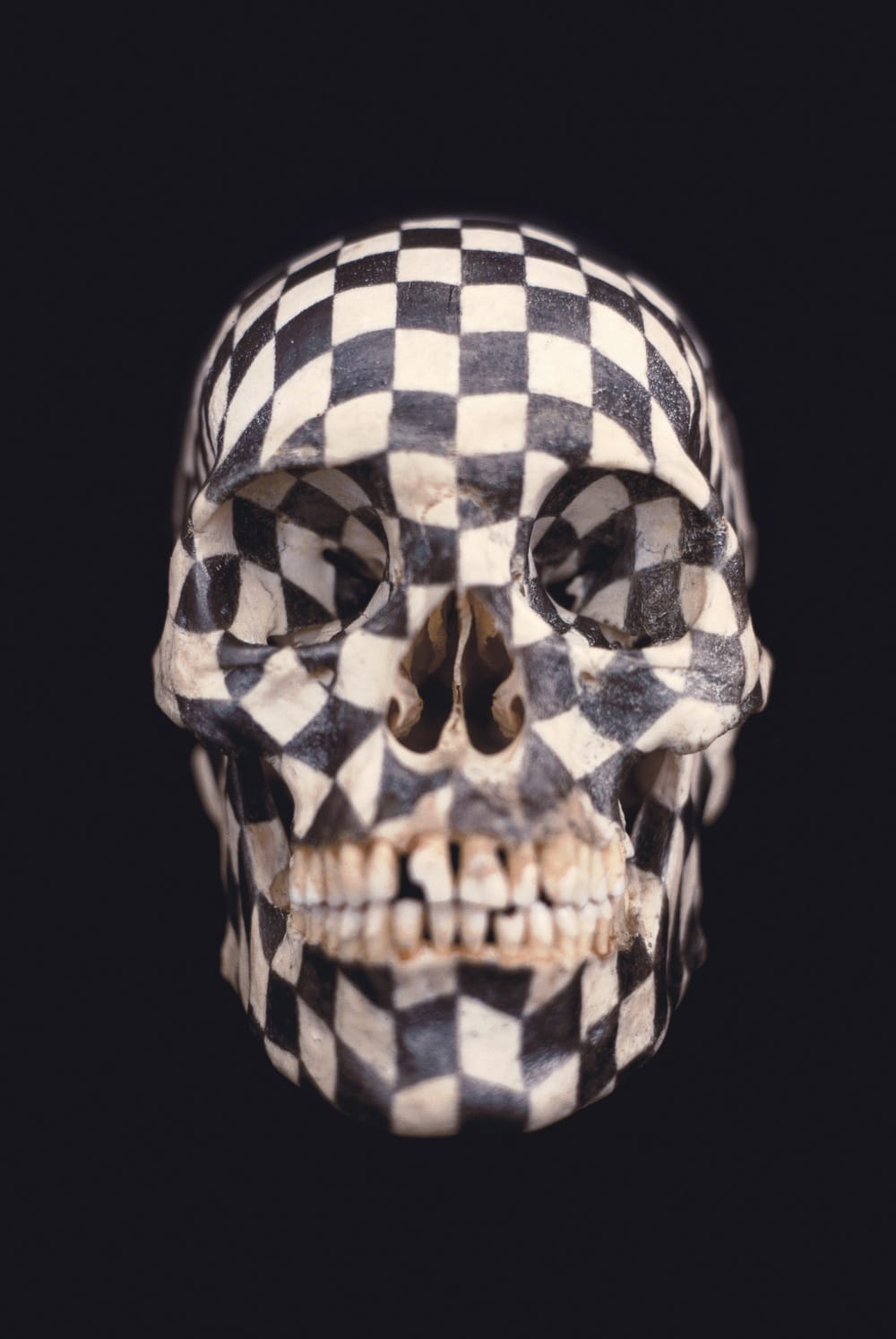

And rapidly the tone shifts – in the next room, Black Kites (1997), a human skull meticulously decorated by the artist with a black chequered pattern stands in the middle of the room. Hung around this image of death there are extracts from the obituaries of complete strangers published in the New York Times. Surrounded by such a display, I could not avoid thinking what line would sum up my life. Will I ever have a line written for me, by those who remain alive after my death?

Walking on through the rooms, I found myself in a floating graveyard. Lintels (2001) is a collection of the lint left behind from the filters of drying machines. When approached closely one can see the residues left, and even make out strands of human hair. Though repulsive at first, it leaves a more lasting imprint that invites a deeper reflection. This piece, first displayed in the aftermath of 9/11, evokes a moving vision of a necropolis; imagine how striking it could have been to those who had just experienced death so closely. In contrast to this, the main room shows an eclectic arrangement of pieces, much more upbeat. The walls of the room are covered by a series of photographs taken in Berlin, where the artist would stop whenever he saw a motorbike the same as his.

Overall, I found that piece dull in the extreme, though together with the other pieces in the room it conveyed a twisted version of the industrialism that surrounds us. More engaging, was the artist’s own reworking of a Citroen DS that dominated the room. The car had been sliced in three, the middle part taken out and reconstructed again to create a sleek car reminiscent of Formula One.

Other pieces in the room left me cold: a random shoebox, remarkable only as having been used by artist, had been placed on the floor, and not very far away there was an empty elevator compartment from a building in Chicago. Nonetheless, there was in that room a piece that struck me: an arrangement of four bikes modified such that they were attached to each other, like a twisting skeleton of worn out snakes biting each other’s necks. Finally, from my visit, one anecdote is fixed in my mind. “Carambole with Pendulum” is a twisted game of billiards where the table is now elliptical, with no pockets and only three balls, one of which is hung by a pendulum from the ceiling. With cues stacked in the corner of the room, anyone can pick one up and play, according to their own rules, this surreal game.

As I’m standing there watching others play, a family enters – two children mouth-full of question followed by two parents. The girl, not older than seven, asks again and again if she can have her go as her father starts playing with the balls and the cue as if he were the child. Meanwhile, the mother contents her with some reasons of why it’s not her turn. This little scene just got me thinking how conditioned most of us have grown up to be, never daring to play after years of parental repression.

Art is a way of demolishing these learnt preconceptions; it is an invitation to those who dare to join the game of observing reality from a different angle and taking part in it. Orozco’s exhibition is definitely a good starting point to embark on this trip – then again, it might just be a break from the adult world of Imperial life.