Can we simply ‘Ctrl+S’ our past?

Jake Lea-Wilson explores the challenges that lie behind ‘futureproofing’ our history

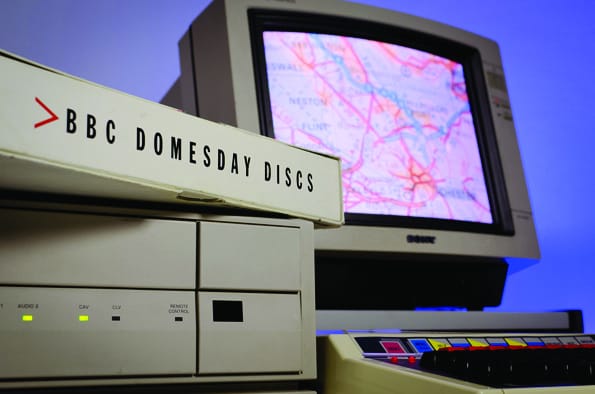

In 1986 the BBC launched an ambitious campaign to repeat the Domesday Book collection of data in the 11th Century. The information was thought lost, a victim to digital obsolescence which is when a form of data storage becomes unreadable due to outdated technology. Through the perseverance and hard work of many at the BBC and The National Archives, the data gathered by over 1 million people has now been made public again after 25 years.

In 1086 William the Conqueror commissioned a survey of the people of England with particular attention to the land and resources owned by residents. It was an attempt to work out the extent of taxes that he could charge in direct correlation to the amount of land that the citizens owned. The two huge Domesday books took a year to complete and William had died before they were finished. Today though, they are described by historians as one of the most important artefacts of the Middle Ages. The books give insight into daily life for the English as well as important population distribution statistics.

Obviously this is a topic most talked about in school history lessons but it’s valid amongst the technology pages because in 1983 an ambitious television producer, Peter Armstrong, at the BBC decided it would be a great idea to repeat the data collection ideas of William the Conqueror but with a technological twist.

Instead of a traditional modern age census this would contain photographs, accurate local area, town and city descriptions as well as accounts of the daily lives of people from all around the country. It was treated as national campaign and was taken up rapidly by local education authorities, schools, colleges and many individuals and families nationwide. Imperial College’s own lecturer Gareth Mitchell was in secondary school at the time and vividly recalls being asked back by his primary school as he was one of the only people that knew how to program the BBC microcomputer with their information.

A mammoth task

Armstrong, whose idea the whole thing was, recruited leading technological minds to the BBC including George North, head of innovation. Overall they had more than 16GB of data (a staggering amount back then) in the form of 1 inch tapes of photographs (in full HD), programmed documents on disks created by the BBC Model B microcomputer from schools all around the country and many papers related to census data and news.

It took two years of consultation, hard work and the finest minds to digitise the information. In 1986 the most prevalent way of transferring information between computers was the 5 ¼ inch floppy disc and unfortunately they were only capable of carrying a maximum 1.2 MB of information. North battled with the problem and eventually it was settled to use an up and coming data storage called Laserdisc. These discs were the size of vinyl records and looked like the CDs we use today. The information was encoded on the discs and the computer along with laserdisc player and Domesday discs were sold as a package for around £5000. At the time this was the same price as a decent car so few schools could afford the package. A few libraries and LEAs bought the system but it was far from a wide distribution. People became angry that the information they had so painstakingly collected couldn’t be seen easily. As time passed the project was continually referenced as a prime example of digital obsolescence. It was only accessible by fewer and fewer machines each year. By 2002 there were barely a handful of machines capable of reading the discs left in the world. What good was a digital archive that only lasted just over a decade when the original Domesday books had lasted over nine hundred years?

Several efforts were made to restore the discs but ended in failure due to lack of budgets or arguments over the way the project should be represented. Computer clubs maintained that the most important factor of the restoration should be the meticulous recreation of BBC microcomputers exactly as they were created. Archivists argued that the data was the most important thing and it should be extracted for use on any modern computer.

Saved at last

Eventually another producer at the BBC, Alex Mansfield, was inspired to retrieve the data and make it available to the public through the internet. He got back in touch with George North, who felt that he had “unfinished business” with the project so was all too happy to start the lengthy process of data retrieval. The original 1 inch tapes were found and scanned, the laserdiscs were converted to a new digital format that could be read by more machines and the map of the UK which held the locations of all the data was resurrected. It took a lot of patience to recreate the technology of 1986 but eventually it paid off.

Online future

The obvious question is how can we guarantee that this won’t happen again? The most important thing when it comes to data preservation and archiving is selecting a safe environment and suitably sustainable conditions surrounding the data. I’m not referring to the direct atmospheric conditions, although this is important, but to the monetary and political situations of the company that retains the information.

The BBC is subject to fashions and budget cuts and wasn’t able to keep updating the data onto new storage formats and it was hence almost lost forever. That’s why they have approached the National Archives in Kew to maintain the data. The National Archives are funded directly by the government and thus are a lot more stable. They have over 11 million categories in their catalogue which doesn’t sound like much but as an example the First World War, just one item in the catalogue, has over 35km of linear corridors full of information. They know how to keep information safe. Tim Gollins, head of Digital Preservation at the National Archives told me why it will work this time around. “It doesn’t matter how good the technology is, it matters where the data is. It’s in HTML on the web and the probability is that we’ll be able to read this is in many years time as the technology is ubiquitous, this is why it will be safer.”

The BBC has now launched its own Domesday website at www.bbc.co.uk/domesday and is fully searchable by postcode. Furthermore there are options to update the information and upload more photos and writings to be preserved for the future (hopefully more successfully this time).