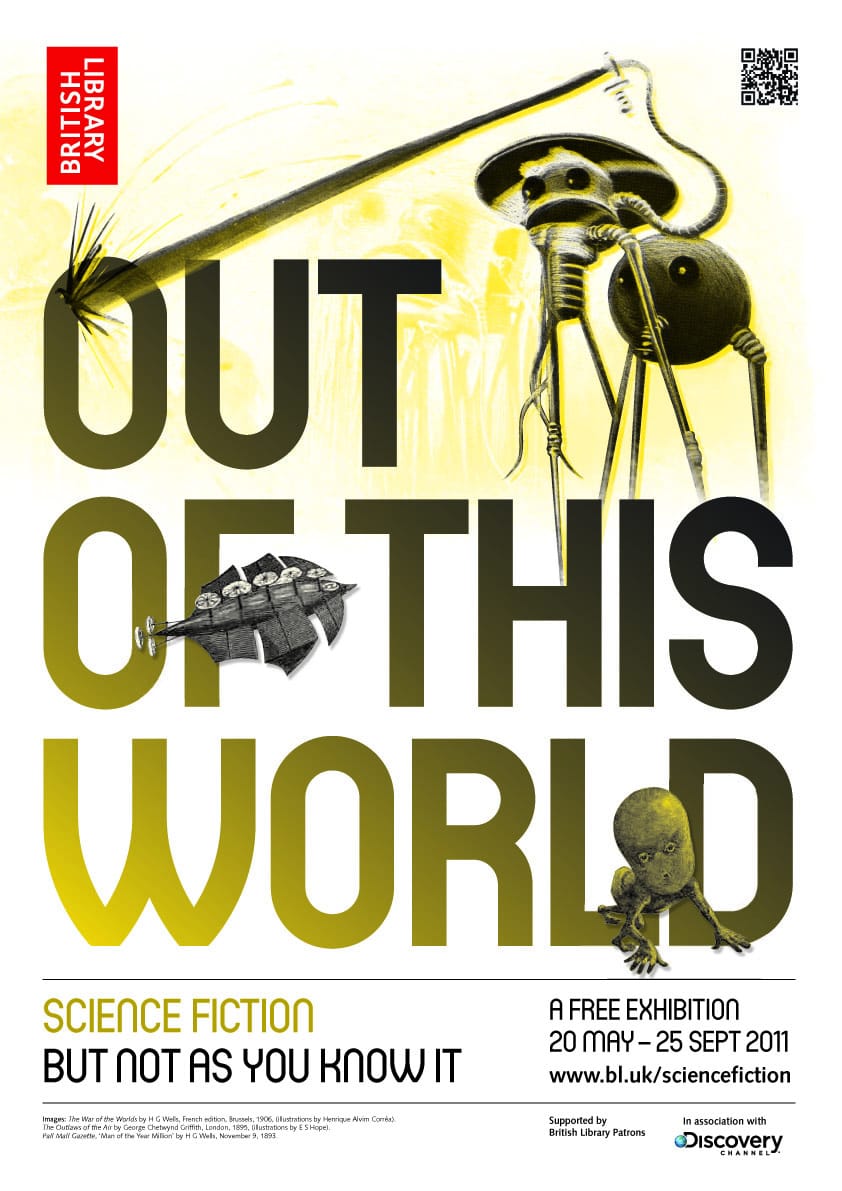

Science fiction, but not as you know it

The British Library’s intrepid new exhibition

The small, dusty and cramped environs of the Imperial College Science Fiction Library may serve as a true reflection of how the genre is valued and viewed by many... and this is the science fiction library of the country’s leading science university. The tiny library houses over 7000 books and 1000 films: extrapolate those figures to get a more realistic size of the realm of science fiction on a global scale.

Despite its geeky connotations, science fiction pervades all manner of media around us, and has done so for millennia. From Thor and Inception to Lucian of Samosata’s True History dating back to the second century AD, which tells of a group of explorers visiting strange lands and then being lifted to the Moon via a waterspout.

Anyone who claims not to enjoy science fiction is probably lying... or at least unaware of the myriad of themes, premises, styles and storylines it encompasses. If you search hard enough through the back catalogue of books and films you have enjoyed, you may be surprised at how many could be classified as such.

Upon uttering the words “sci fi”, it is easy to immediately conjure images of aliens or scenes from Star Trek. And, undoubtedly, these fall very much under the category of sci-fi. As humankind develops, time moves forward and technology progresses so too does the types of science fiction we create.

It helps us confront ethical issues associated with the exponential expansion in our scientific knowledge and the added responsibility to planet and people it entails. It lets us come to terms with uncomfortable truths and uncomfortable potential truths; it gives us free rein to philosophise about the nature of reality and our place in the world; it allows denizens living under authoritarian governments to satirise and question the status quo; and, in a very Freudian way, it gives us an arena in which to escape and act out “illicit” fantasies.

Utopia is still a thoroughly contemporary concept. Both it and its opposite, Dystopia, have been a subject of investigation in fiction such as Aldous Huxley’s outstanding Brave New World and George Orwell’s 1984. However, the word was coined around the time of King Henry VIII by Thomas More, one of his loyal advisors, in a book he wrote describing the political system of an imagined world.

Cyrano de Bergerac also dabbled in the world of the fantastical. His 1657 book, Le Autre Monde: ou les États et Empires de la Lune (The Other World: The States and Empires of the Moon), Cyrano travels to the moon on a rocket powered by firecrackers to meet its inhabitants. One hundred odd years later and vehement supporter of civil liberties, Voltaire, published Micromégas – recounting the tale of a being who visits earth from another planet.

More modern sci-fi offerings include the epic Dune by Frank Herbert in which he creates in infinitesimal detail another world: replete with all the details of its own political, cultural, religious and social practices. Whether your interests lie in the scientific, the romantic or the aesthetic, Dune is guaranteed to enrapture you on at least one dimension.

What the world will be like in the future is another fascination of science fiction. Before the flurry in technological development of the 1700s, life did not alter greatly from generation to generation. The apparent absence of change would have also meant an absence of realisation that life over the coming decades and centuries would be different. The complete opposite is true now. Cormac McCarthy’s highly acclaimed book, The Road (also made into an intensely moving film by John Hillcoat starring Viggo Mortensen), gives us a harrowing vision of a post-apocalyptic earth.

A copy of the Daily Mail from the early twentieth century, but dated Saturday 1st January 2000, gives a snapshot of how people (or at least Daily Mail editors) thought Britain might be at the turn of the millennium. Yet more interesting is William Heath’s illustration March of Intellect, depicting the Grand Vacuum Tube Company’s (grand vacuum tube) running from London to Bengal and an apparently steam powered carriage – London to Bath in 6 hours – among many other new fangled, futuristic inventions of Heath’s imagination.

The above are but a few small rays of light that the British Library’s Out of This World exhibition shines on the super genre. The high-ceilinged, dark, cool interior of the PACCAR gallery creates a calm and reflective setting for its collection of literature, film, illustration and sound. Mixed with copies of original manuscript from the sixteenth century are interactive exhibits including a design your own alien station (your creation will be put on display after a mandatory trip through quarantine) and a chance to have an instant messaging conversation with a computer to test whether Artificial Intelligence can truly replace Human Intelligence. I got a wonderful smug sense of satisfaction when I succeeded in outwitting “Elizabeth” after my second question put to her.

The guest curator, Andy Sawyer, director of Science Fiction Studies MA at the University of Liverpool, has organised the collection into sections – Alien Worlds; Future Worlds; Parallel Worlds; Virtual Worlds; the End of the World and the Perfect World. These give us a framework with which to consider sci-fi as well as demonstrating the extent of its scope.

Lose yourself – for free! – in the countless concepts, presented succinctly and beautifully, at the British Library’s Out of This World. Give yourself a different perspective so that you may, perhaps, gain a more enlightened perspective on what you perceive to be reality.

Out of This World runs from 20 May – 25 September 2011. www.bl.uk/sciencefiction