Grandma, Alzheimer’s and me

A very personal account of the impact of this terrible disease

It’s a strange feeling when you first step into an Alzheimer’s care home. What hits you immediately is the smell of urine and cheap school dinners, but the far more unnerving aspect is the sea of blank faces that greets you. I’m here to see my grandma, who has been suffering from Alzheimer’s for a number of years.

As I progress down the thick-carpeted hallways towards her room, my gaze catches a group of people sitting in easy-chairs in a loose circle, facing each other as if to facilitate conversation. But they’re not here to talk; instead, they mumble away to themselves, uncertain of where they are, forced out of their own homes into one that’s been chosen by their children for convenience.

When I finally get to my grandmother’s room, I gingerly loiter at the door: she’s tucked up in bed, being carefully fed by a nurse. I feel like a voyeur, like I’m watching something I shouldn’t, witnessing the cyclical nature of life, and death, as my grandma is fed like a baby. At first I’m not sure if this is the right room, as her complexion shocks me. This is not the person I knew before, who helped me build sandcastles, and fish in rock pools on carefree school summer holidays spent in Dorset. Instead, her weathered skin loosely wraps her toothless skull, her thick-rimmed glasses magnifying tired, confused eyes.

At first I just stand there, rudely staring, but the nurse catches my eye and smiles, gently moving closer to grandma, “There’s someone to see you Betty.” “I don’t want to see anybody,’’ comes the curt response, but I enter anyway and sit on a chair in the corner of the room, as the nurse helps her out of bed and into a chair. It’s not that she doesn’t want to see me, I tell myself, it’s just that she’s probably scared, and doesn’t know who I am.

It wasn’t until 1906 that a German doctor called Alois Alzheimer first identified the disease that came to be named after him. Despite this, it was only much later that it was characterised as a neuro-degenerative disease, caused by the misfolding of certain proteins in the body.

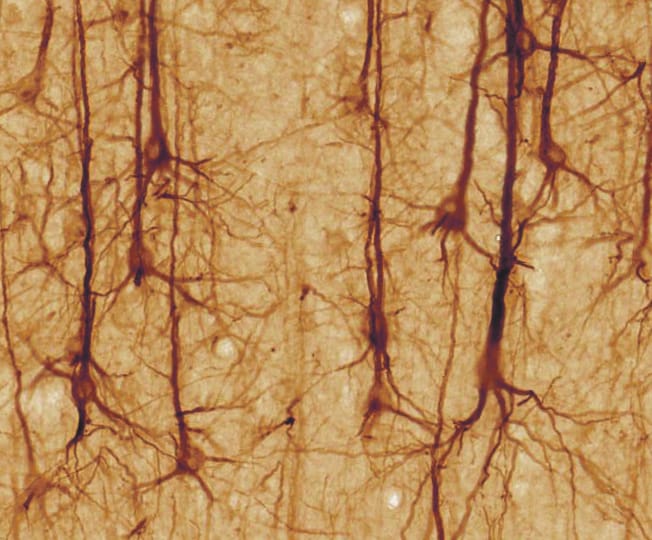

It is the misfolding of two proteins – amyloid and tau – which causes them to clump and tangle inside brain cells. The continual build-up of plaques and tangles eventually causes the cells to die, explaining the progressive loss of brain function that characterises Alzheimer’s.

Despite the fact that Alzheimer’s has been known about for over a century, treatment is still relatively primitive. But researchers at the University of Cardiff have uncovered a new molecular interaction that may help us understand what causes Alzheimer’s in the first place, and design better treatments.

Instead of looking at traditional targets of tau and amyloid in isolation, the team led by Professor Trevor Dale, looked at the interactions between amyloid and nucleic acids – the building blocks of DNA. Together the two can combine to form Amyloid-Nucleic Acid (ANA) fibres, which can also cause deadly plaques in the brain.

According to Professor Dale, the findings could have “importance for Alzheimer’s disease because it may be that we can find a way to stop the ANA fibres forming and protect the brain from harm.”

While long-term drug development prospects for Alzheimer’s are poor, Professor Dale said that “continued funding and basic research will be essential”, especially as the number of sufferers in the UK will continue to rise to an estimated 1.7 million by 2050.

This is something Dr Simon Ridley, Head of Research for Alzheimer’s Research UK, echoed, as “research is the only answer to heading this off, giving us hope of new treatments and better evidence for prevention. We must invest in research at all levels now to avert a dementia crisis in the next generation.”

It’s a sobering sight to see my grandmother, once close to six feet tall, now huddled, diminished and shrunken in a chair. But when her weathered face breaks into a toothless smile as she recognises me for a few brief moments, I realise how important it is for more money to be pumped into research, in the hope that a potentially breakthrough treatment can be made available to help ease the suffering of patients such as grandma.