While you were away...

As term begins, we sift through Imperial's science headlines to bring you the latest news

While you’ve been busy travelling the world, waiting for term to start, the staff at Imperial have been pushing the boundaries of human knowledge. The keen students amongst you may be aware of what headlines Imperial has been making over the last few months. But for those of you whose New Scientist subscription was ended abruptly as soon as you got your offer, Felix Science has a round up of some of the most interesting and important science coming out of the College this summer.

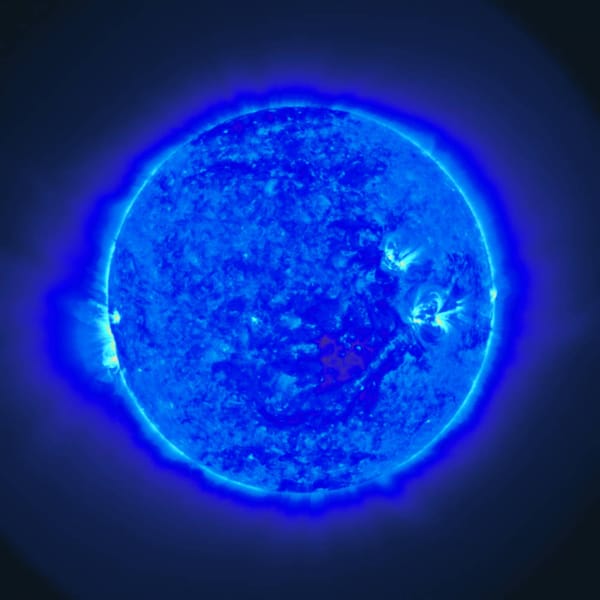

Most distant quasar discovered

Light from a quasar 13 billion light years away reached the UK Infrared Telescope in Hawaii late last year during an infrared deep sky survey. A light year is the distance travelled by light in one Earth year, so we’re seeing the quasar as it was 13 billion years ago — only 770 million years after the Big Bang. It’s the most distant quasar ever discovered. The finding was announced in a paper in the journal Nature in June. Lead author on the paper was Dr Daniel Mortlock from the Physics department at Imperial.

A quasar, or “quasi-stellar radio source”, is the active nuclei of a distant galaxy. It surrounds the central black hole of the galaxy and is powered by a disk of material accreted on to the black hole because of its huge gravitational pull. The material, mainly gas, becomes very hot and emits a considerable amount of ultraviolet radiation. As the radiation travels across the universe to us it becomes stretched due to a phenomenon known as redshift. This shift in wavelength allows astrophysicists to calculate how far the light has travelled.

The newly discovered quasar, known by the catchy name ULAS J1120+0641, is 2 billion times as massive as the Sun and lies in the constellation Leo in the night sky. It is a hundred times brighter than anything else discovered around the same distance away, meaning it will be able to give us a unique insight into the universe when it was just beginning.

Potato genome sequenced

This summer, the humble potato became the first major UK crop plant to have its genome sequenced. Before it had its genetic make-up studied in detail, new varieties of potato took between 10 and 12 years to breed. This process should now be sped up considerably thanks to an international collaboration of researchers, which included a member of the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial: Dr Gerard Bishop. The all-important details were published in the journal Nature in July. In the UK we each eat, on average, 94kg of potatoes a year. They are becoming more popular across the world, too, especially in Africa and some parts of Asia — upping the role of the potato in global food security. By 2050, 9 billion people are expected to be living on the planet. Engineering a potato with greater water uptake and disease and drought resistance will become increasingly necessary as the world population grows and there are more and more mouths to feed. Having the potato genome is going to make doing that a whole lot more feasible.

Identity-shifting neutrinos

Neutrinos are slippery particles by nature because they do not interact with matter, generally passing through it completely undetected. Now particle physicists might have found another side to their inherent elusiveness: a new way to shift their identity. Results from the T2K neutrino experiment in Japan show a new type of “oscillation” that would allow neutrinos to change type in a way not seen before. While looking at neutrinos from the Sun in 2001, physicists finally proved suspicions they had held since the 1960s that two types of neutrino oscillation can occur. There are three types, or flavours, of neutrino in all. One is paired with the electron and known as the electron neutrino. The other two are paired with the muon and tau leptons, fundamental particles that are identical to electrons except for larger masses. Electron neutrinos had been observed changing into muon and tau neutrinos in the 2001 results. The transition physicists think they may have just seen would complete the set — it is the only transition that is thought to be possible theoretically but that has not yet been seen in reality. But, it’s not quite that simple. There is still a small but not insignificant probability that the results seen occurred, not because of a new oscillation, but simply by chance. This means that, though the results do indicate that this third type of oscillation did occur, they do not show an outright discovery. Imperial’s Professor David Wark, who leads the UK’s involvement with the T2K experiment, said that on a scale ranging from “maybe” to “probably” to “almost certainly”, the new result puts us somewhere between the latter two. The results were published in Physical Review Letters in June.

– Kelly Oakes

Smart materials make proteins form crystals

Scientists at Imperial teamed up with the University of Surrey to develop a new method to enable the formation of crystals from proteins using ‘smart materials’ which are able to maintain the shape and characteristics of the molecules. The method should boost research into new medicines, assisting scientists in working out the structure of drug targets. Developing new drugs involves identifying the structure of proteins associated with a disease and designing molecules that can block their function. The researchers developed an effective means for crystallizing proteins using Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), which intrinsically bind together around the outside of a molecule, leaving it with a strong likeness to the original target shape when the molecule is extracted.

Previously, scientists have obtained useful crystals for fewer than twenty per cent of proteins identified as potential drug targets, the number of which is increasing exponentially. The ability to remember attributes of molecules make the MIPs ideal nucleants, making it easier for protein molecules to bind and form crystals. The research, led by Professor Naomi Chayen from the Department of Surgery and Cancer at Imperial, was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and the European Commission.

The researchers found that six different MIPs induced crystallisation of nine proteins, providing results in conditions that would otherwise not cause crystals to form. Professor Chayen commented, “[MIPs can produce] better crystals than we can with other methods. This is a really significant innovation that could have a major impact on research leading to the development of new drugs”.

Statins found to reduce risk of death from infections

Unexpected findings by researchers suggest that statins, medication for reducing cholesterol and lowering the chances of suffering heart attacks and strokes, may stop deaths from infections and respiratory illnesses. Professor Peter Sever, from Imperial’s International Centre for Circulatory Health, presented the results at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology on 28 August. Professor Sever and his research team inspected the death certificates of nearly 1,000 people who were among 10,000 volunteers with high blood pressure testing atorvastatin, a type of statin, for the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (Ascot). They found that eleven years after the trial, deaths from infections and respiratory problems were 36 per cent lower than with those given a placebo. The statins appeared to reduce the production of inflammatory agents in the blood that are toxic and stimulated by infections.

Professor Sever said, “this study is going to make people think more about the non-cardiovascular benefits of statins”. It is suggested that patients with a high risk of developing pneumonia could be prescribed the drugs, and Professor Sever added that there now was an “emerging evidence base for statins protecting against infections” while warning against widening statin prescriptions based on one study.

Studies have shown statins have potential side effects such as muscle weakness and liver and kidney problems. The death rates from cancer within the Ascot study showed no difference. At the same time, Professor Sever mentioned he has “no reason to believe atorvastatin is unique in these non-cardiovascular actions”. The drug is taken by up to seven million people in Britain.

– Alex Karapetian