It’s raining methane

Planetary scientists come up with weather system model for one of Saturn's moons

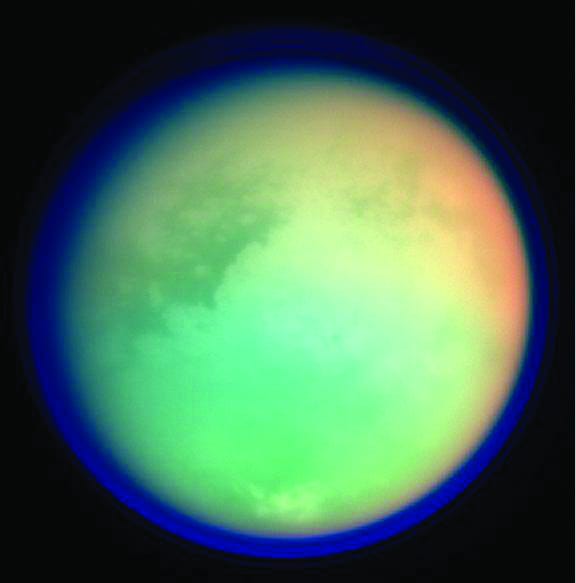

Scientists have developed the most advanced model yet of the weather system on Titan, one of Saturn’s moons and the only place in the solar system other than Earth that harbours lakes.

Instead of water, Titan’s lakes are filled with methane, a molecule made of one carbon atom and four hydrogen ones. The temperature on Titan is around -180 °C, which is just right for methane to exist in three different states: solid, liquid and gas. The lakes on Titan form part of a whole weather system, that works in much the same way as the water cycle does on Earth. Vast clouds that cover the surface for most of the year (one Titan year, that is, which is equivalent to 30 Earth years) made up of evaporated methane from the surface, that eventually precipitates back down to fill the lakes again.

Observations made by the Cassini spacecraft currently in orbit around Saturn show that lakes are not scattered across the surface of Titan uniformly, but instead tend to cluster around the polar regions. Clouds also appear to cluster near the poles at middle and high latitudes in the summer hemisphere, which until recently was the southern hemisphere.

Dr Mueller-Wodarg, a planetary scientist in the Physics department at Imperial explained, “Recent Cassini observations have made a direct link between changes in clouds and changes on the ground in terms of the sizes of lakes, hinting at actual weather events occurring right now.” Previous models have tried and failed to explain all of these observations, but now a group of Caltech researchers think they can do just that using a new model that is a cut above other attempts. For starters, it is 3D rather than 2D, and includes more detail about the transport of methane from the surface to the atmosphere, and vice versa. It also takes into account surface reservoirs of methane and how they change over a year.

The Caltech team, led by Professor Tapio Schneider, produced simulations that reproduced the distribution of clouds that has been observed by Cassini and the right distribution of lakes. Mueller-Wodarg said that through the Caltech team’s work “we have gained a first understanding of what controls these features.”

Schneider and his colleagues think that because there is less sunlight at the poles of the moon, on average, it is easier for lakes of methane to accumulate there. In places where there is a lot of sunlight, its energy would cause the methane to evaporate and prevent the formation of such lakes.

The Caltech team simulated the interaction between the surface methane and that in the atmosphere in more detail than has been done before.“The wind system calculated by the model, which plays a crucial role in globally distributing methane, appears to be quite realistic. This is important since only a single wind observation, from the Huygens probe, is available near the surface, so we rely on models to calculate them” said Mueller-Wodarg.

Armed with this new model, scientists working on Cassini will hopefully now be able to plan observations so that they can test the predictions made by it. Mueller-Wodarg added, “We will now be able to predict cloud occurrences and specifically look for the predicted clouds.”

DOI: 10.1038/nature10666