About turns on the road to academia

With Nature citing the number of PhDs as “growing like mushrooms”, is the doctorate in need of reform?

In the age of privilege, when very few attended and graduated from university, achieving the degree of Doctor was a rare feat even amongst the educated. Doctors were revered in many of the royal courts of Europe and granted privileges reserved only to the highest peers of the realm: in Spain, France, the Holy Roman Empire and Portugal, doctors were exempt from uncovering their heads in the presence of the sovereign, and were allowed to address Him without previous questioning. Even the awarding of such PhDs was performed differently – these were not, for instance, awarded after a dissertation had been submitted, but instead granted to honour the academic career of the holder who, for one reason or another, had been deemed sufficiently distinguished as to deserve a doctoral degree. PhDs were thus intimately linked to academia – to the point that they were seldom awarded out of it – and doctors inevitably pursued academic careers because it was the only way of being awarded such degrees in the first place.

In the first half of the 19th century German universities redefined doctoral degrees to their present form: degrees granted after a period of thorough research leading to an original scientific contribution. American universities soon embraced this model and, begrudgingly, European universities such as Oxford and Cambridge ended up applying it too. However, the view of PhDs as academic-leading degrees still holds on in society.

Considering the high specialisation required of PhD candidates, both at the point of application, as well as in what is delivered – the programme content, this view is hardly surprising.

On average it takes at least 3 intense years to complete a PhD, and combined with the three to four years spent obtaining requisite Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees, makes doctorates palatable only for those with a strong bent towards a career in research. While the private non-academic sector does conduct significant amounts of research, this often does not include research deemed as risky, audacious or too vague, so that even in the USA most research is publicly funded and, excluding research laboratories, carried out in or around universities.

And then PhD programmes themselves are often shaped in such a way that doctoral students are trained for nothing but research and academia; skills such as team working, management, business, accountancy and law are often completely neglected in the pursuit of pure knowledge. It is no surprise that after such an upbringing most PhD candidates show a preference for academic careers when asked about their future employment preferences.

Besides, the huge spread of university graduates in the last few decades has led to a steep increase in the amounts of doctors, drawing the editors of Nature to declare “PhDs now grow like mushrooms”. As they pointed out some months ago, the number of doctorates earned each year has grown by 40% in the OECD countries during the last decade, and with a limited number of academic positions available, many such PhD graduates will never get jobs to match their qualifications; supply has outstripped demand.

This has two main consequences. For one, it makes the entry to an academic career a tighter competition. PhD holders are forced to gain better qualifications and improve their academic CVs, often by taking successive poorly paid postdoctoral positions. In many disciplines, having completed a few years of postdoc work is already an a priori requirement for an academic position, and in some extreme cases such as life sciences, people may well need to spend between five and ten years doing postdoctoral work before even being able to apply for a tenured position, which even then, is not guaranteed to be successful.

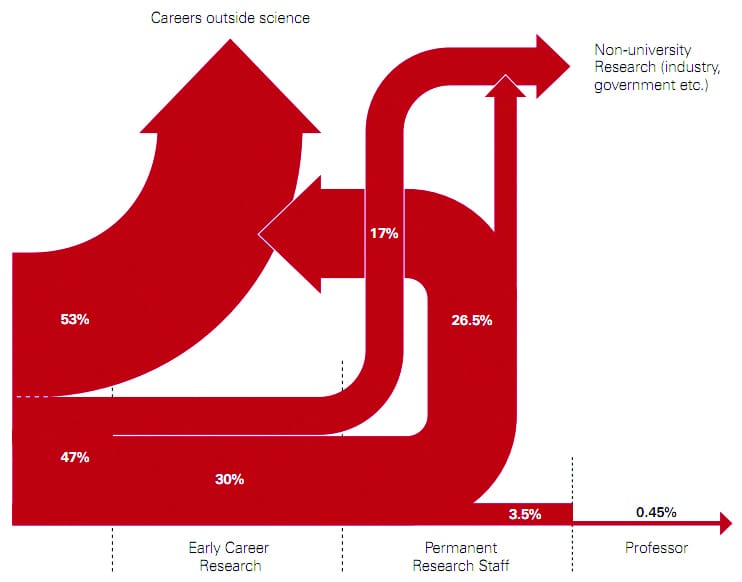

Recent data published by the Royal Society shows that of all PhD holders, 47% opt for what they euphemistically call “early career research”, i.e. postdocs. Statistics show that only 3.5% of PhD holders will ever manage to become permanent research staff – academics – however, and even fewer (about 0.45%) will become university professors. With about 17% of PhD holders undertaking non-academic research careers, the overwhelming majority of PhDs end up in careers outside research.

This majority was recently reviewed in the New York Times. In an article titled “Is a Master’s the new Bachelor’s?” the NYT analysed the difficulties many Bachelor’s degree holders face when looking for graduate job positions owing to the ever increasing number of better qualified (Master’s, in this case) degree holders. These Master’s holders, in turn, struggle for job positions that were traditionally held for them, due to the widespread proliferation of the even more highly qualified doctors. Hence, the second consequence: the proliferation of academic degrees seems to have diluted the value of each qualification, and is thus changing the requirements on careers outside academia too.

While the situation is an unhappy one for Bachelor’s and Master’s degree holders, PhDs working outside academia often see themselves in positions for which they are overly qualified and underpaid. As was pointed out in Nature, PhDs themselves are not linked to significant gains in terms of salary – being only about 1-3.5% higher than that of Master’s holders – nor in higher job satisfaction. The biggest beneficiaries of this situation are the private companies, able to hire more highly qualified candidates for less.

Over time, voices claiming for another redefinition of doctoral degrees are becoming louder. Arguing that the proliferation of PhDs is leading to the above described dilution of the degree, it has been proposed that PhDs should be re-shaped to better match the needs of the job market, and less so those of academia. Current EPSRC-sponsored EngD and Centres for Doctoral Training seem to be leaning in that direction, but question is whether a mere reform of PhD programs is all PhD degrees need in the modern world.