Deadly snake venom better pain-killer than morphine

Black mamba venom proves to be more useful than meets the eye

Few of us associate the black mamba, one of the world’s most venomous snakes, with pain relief. But findings recently published in Nature show that black mamba venom may be a more effective pain-killer than morphine.

The black mamba, Dendroaspis polylepis, is feared throughout southern and eastern Africa for its extreme speed, length, aggression and lethal toxicity.

However, the French scientists involved found that its venom not only served to abolish pain in mice, but did not cause any side-effects. Morphine, commonly used in anaesthesia to reduce pain, has myriad side-effects, the most dangerous of which is respiratory failure.

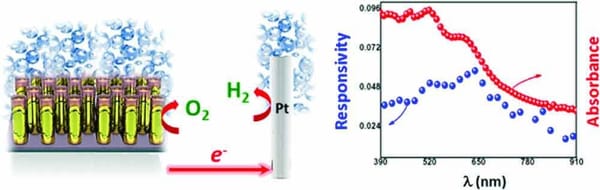

Snake venom can be so deadly because it attacks key ion-pathways across neuronal membranes. We rely on this transport of ions to communicate vital information around our brain and body. If these pathways are prevented from working as normal, our entire neuronal super-organism breaks down – signals cannot be passed around the body. But some signals communicate unpleasant sensations, like pain.

Black mamba venom contains pain-killing proteins called mambalgins. These mambalgins block the acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) in the cell membrane. ASICs are principal players in the pain pathway.

But a perplexing question remains: why does venom of such legendary toxicity contain pain-killing proteins? This is a question nobody seems able to answer.

The black mamba is not the only venomous snake with a potential benefit to medicine. There are already three drugs on the market based on snake venom proteins. Eptifibatide and tirofiban are derived from anticoagulant proteins found in the venom of the southeastern pygmy rattlesnake and African saw-scaled viper, respectively. Both drugs are used to treat sufferers of angina or heart attacks. Contortrostatin, a component found in copperhead venom, is being used to attack breast cancer cells and to prevent cancer from spreading.

In fact a plethora of highly toxic animals – and of course plants – exhibit this ‘poison paradox’. Cone snails are predatory sea snails. They hunt and immobilize prey using a radular tooth and a poison gland containing neurotoxins. In 2004 the Food and Drug Administration approved the pain-killer Ziconotide, derived from snail cone toxin, for use as a non-addictive pain-killer substitute for morphine. The venom of the Israeli yellow scorpion contains a protein that binds to cancerous cells found in gliomas, a type of brain cancer. When combined with a radioactive solution, this protein can target and destroy glioma cells – and ultimately the cancer. As research progresses the number of these highly useful animal and plant-derived compounds will only increase in number.

So it seems there is a charitable flip side to these venomous creatures that are making up for countless lost lives.

DOI: 10.1038/nature11494