From stem cells to sex cells

Stem cell research receives another vital boost. Fiona Hartley reports

Japanese researchers have created viable eggs in mice from skin stem cells which produced healthy fertile offspring that successfully had their own progeny. This breakthrough could hopefully lead to treatments for human infertility in the distant future.

Stem cells give rise to all specialised cells in the body, and are also self-renewing to produce more stem cells. Stem cells in humans come in two basic forms: embryonic stem (ES) cells and adult stem cells. ES cells were ethically controversial because of the embryonic destruction required to harvest them. In 2006, Shinya Yamanaka succeeded in reprogramming adult stem cells to an ES cell-like state. These cells were named induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Yamanaka won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for this work just this week.

Mitinori Saitou and his team from Kyoto University, the authors of this study, have previously made functional sperm cells from adult cells in mice, which were used to successfully fertilise eggs. Their new study, published in Science last week, shows that a modified version of the system they used to make sperm can also make eggs that, importantly, give rise to healthy progeny.

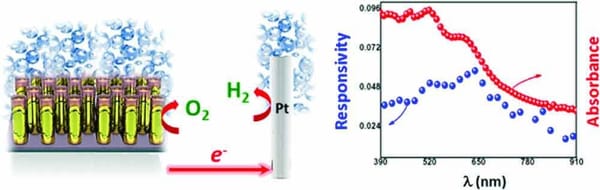

The group applied a mix of signalling molecules to turn ES cells and iPS cells (derived from skin stem cells) into primordial germ cells (PGCs), the precursor cells to sperm in males and oocytes (eggs) in females. The PGCs were then added to embryonic ovary tissue, making “reconstituted” ovaries. This mixture was transplanted into female mice, where immature oocytes developed. The immature oocytes were removed, and allowed to mature in vitro. The team then fertilised the mature oocytes with mouse sperm. The resultant embryos were transplanted into surrogate female mothers, and these embryos developed into fertile mice.

Saitou and colleagues are now investigating whether PGCs can be made from adult human stem cells. This may prove difficult because of differences between mouse and human cells, but the ultimate hope is that one day this technique could be used to make eggs to help infertile couples have children. Scientists have cautioned that a lot of work remains before this goal is remotely achievable though, including ethical considerations about using human ovary tissue to culture the cells. The immediate impact of the study will be to provide a robust system for further investigation of mammalian female germ-line development, the poor understanding of which is one of the reasons why the research does not yet have any current clinical relevance.