Gold for Bronze

The Royal Academy succeeds with an exhibition on bronze sculpture throughout history

Classically, bronze is thought of as the material of antiquity. The discovery of the endurable properties of such copper alloys certainly allowed our ancestors to make more robust tools and weapons than their stone-age predecessors. Its use as an artistic medium, however, from the ancient world to the modern day, cannot be overlooked. The impressive exhibition of Bronze, currently running at the Royal Academy, eulogises the versatility and beauty of this abiding material, with a collection of artworks and artefacts spanning over 5,000 years of history.

As the arduous process of casting was perfected by the Greeks, it is only just that the exhibit opens with the Dancing Satyr. Despite displaying the Ancient Greeks’ obsession with the muscle architecture of the male form, this stunning statue is far from the generic images of Grecian Gods and Heroes, wrestling with foul beasts, which we are so used to. Instead it depicts a satyr vigorously throwing himself into a dance. At first it may appear to be a human figure, however, while encircling and studying the form, his satyr features become visible; pointed ears, wild expression and the hole from which his tail would have once protruded. The metallic green colouring, due to a high copper content in the bronze, gives the figure an earthly glow and his fragmented limbs add to the mysterious quality of the piece. I find it very fitting that he was discovered by fishermen off the coast of Sicily. Researchers have dated this statue to the Mid-Late 4th Century BCE and believe that he was originally one member of a whole throng of dancing satyrs. As this solitary figure has been tantalisingly positioned in the centre of an otherwise empty room, the viewer is provided with the physical space to imagine the rest of his party, dancing around in the twilight.

Dexterously, this vast collection has been organised thematically, rather than periodically, making it an absolute feast for the eyes. Where else would you see a medieval Sanctuary Ring door knocker from Durham Cathedral alongside a bronze Basketball by Jeff Koons? Or how about exquisitely decorated vessels from the Shang dynasty next to Jasper Johns’ 1960 Painted Bronze (Ale Cans)? The scope the curators have given for the comparison of these objects allows us to gain an appreciation for the adaptability and the fathomless importance of bronze throughout the ages. The endurance, hue and finish of bronze have proved it to be an ideal material for creating giant, imposing statues of Gods and Heroes. I feel myself cower beneath the colossal figure of Perseus, as he stands over the writhing body of Medusa and holds aloft her severed head. This sculpture is the 1844 cast of Benvenuto Cellini’s masterpiece from the 1550s, ordered by the Second Duke of Sutherland, representing within the collection the long-established obsession that the British have with the Florentine High Renaissance.

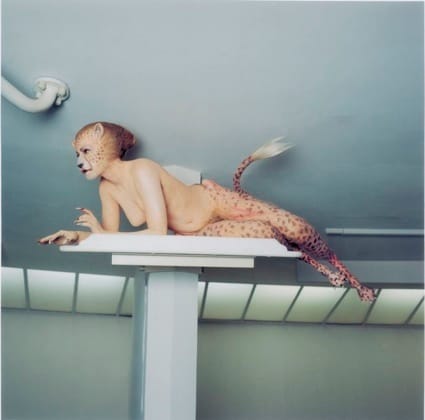

Bronze animals are also profoundly delineated in this exhibition, most notably by the intimidating Etruscan beast, the Chimaera of Arezzo. I am overwhelmed by the sheer skill it would have required to create such a ridiculous looking creature; a fire-breathing lion, with an extra goat head on its back and a snake for a tail. Other fabulous animals on display include The Porcellino, a life-sized boar by Pietro Tacca’s, Louise Bourgeois’s 1996 Spider IV and Picasso’s car-faced Baboon and Young. Juxtaposed against these comparatively modern pieces, is the exquisite Danish Nordic Bronze Age statue the Trundholm Chariot of the Sun. According to the Norsemen, everyday Sól, the sun goddess, with her horses Arvak and Alsvid, carried the sun across the sky on a chariot. It is, therefore, highly possible that this sculpture once had a rider. It is very sophisticated, especially for such an early piece (dated to 14th Century BCE) and the embossed gold leaf on the sun is simply gorgeous. This, along with Alfred Gilbert’s St. Elizabeth of Hungary; depicted with a forlorn, ivory face amongst cascades of bronze roses and finery, are my two favourite objects within this extensive collection. They demonstrate how bronze can be manipulated into finer and more delicate objects, rather than just giant, majestic characters of grandeur.

Bronze will run at the Royal Academy until 6th December. It is definitely worth visiting; many of the artifacts on display have never before been exhibited in England, and possibly never will be again. Bronze at the RA, until 9 December. Tickets from £9 for students.