Solar cells get a boost

New technologies promise improved efficiency

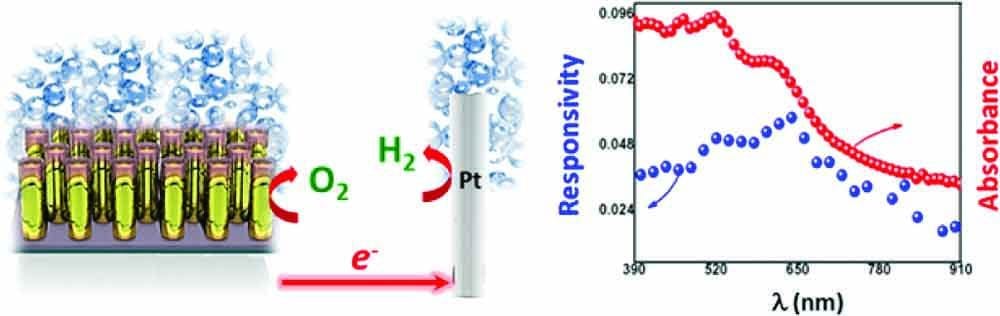

Scientists at the University of California Santa Barbara have developed an improved method of generating solar electricity. Rather than making use of the photoelectric effect, this newly designed solar cell generates electricity while splitting water into oxygen and hydrogen gas. In the past, the main difficulty in building such cells has been finding a catalyst that isn’t simply oxidised by the highly reactive molecular oxygen involved in the process. Recent developments in the field of cobalt-based catalysts have now made them a more feasible alternative.

The cell makes use of a phenomenon known as surface plasmon resonance (SPR), which is the resonant oscillation of valence electrons in a solid when it is hit by photons of the electrons’ natural frequency. The main benefit of SPR is that the energy can be built up gradually, as each incident photon of a sufficiently similar frequency contributes. This is not the case in cells using the photoelectric effect, where only high-frequency photons (in the UV range) have any effect – the energy of lower frequency photons is wasted. In SPR, the amount of energy generated is simply proportional to the intensity of incident light.

Plasmons are best excited by photons in the visible spectrum. This is another advantage over photovoltaic cells, which can only use photons in the UV spectrum; the Earth’s atmosphere is an excellent absorber of UV light, which is good news for our skin, but inconvenient for any method of generating electricity which relies on UV photons. Visible photons are much more abundant on the Earth’s surface. The fact that visible photons have a lower frequency and thus less energy to give would decrease the system’s efficiency, as three or four photons are needed to release a single electron, but this is more than made up for by the increased number of usable photons.

Usually, the difficulty in using SPR to generate electricity is doing so without damping the oscillating motion to the point of uselessness. The device designed by the group of scientists solves this issue by using titanium oxide-capped gold electrodes. These rods are only 90 nm in diameter; an array of them is then connected to the platinum counterelectrode (where hydrogen is evolved). The small size of the rods limits the extent of the plasmon’s motion, reflecting it back onto its own path, creating an interference pattern, which in turn generates a stronger electric field, causing the electrons to pile up towards the ends of the rods. The titanium oxide at each end acts as an electrical insulator, which seems counterintuitive at first, but turns out to be an excellent way of regulating the amount of energy released from the surface plasmon. Only electrons of very high energy manage to tunnel through its structure, and these are then used to generate current, while the bulk of electrons remain, and continue to power the SPR process.

The “holes” left behind by these high-energy electrons act like positive charges, being transferred through the cobalt-based catalyst wrapped around the centre of the rods, and used to combine oxygen radicals into oxygen gas, completing the reaction.

One aspect of the process is yet to be explained by any involved parties. After being exposed to a light source, the generated current density jumps to some high value, as expected. However, instead of plateauing very quickly, it then proceeds to slowly increase by another third of the original value. None of the physical processes involved should take more than a few seconds, and yet the current density continues to change for much longer than this. Further investigation is thus necessary to fully explain the phenomena involved.

DOI: 10.1021/nl302796f