Sex? Completely Overrated

Charlie Owen discusses why one class of creature shuns sex

As much as you may think the contrary, and that this advice is hardly required for the average Imperial student, avoiding sex is really quite difficult. That is, for a species to survive, its genome must be kept up-to-date through the ‘shuffling’ effects of recombination and sexual reproduction. Without it, evolution simply can’t happen quickly enough in the fight against threats such as parasites.

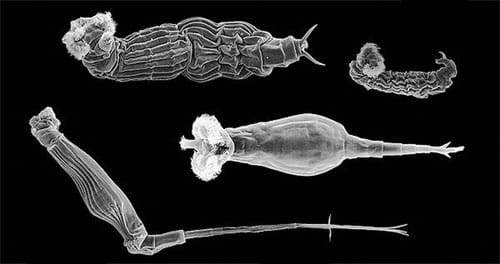

Enter the bdelloid rotifers – truly inspiring creatures, am I right? Well, okay, but most biologists at least hold some respect these tiny little freshwater organisms. Take a sample of water from a pond or some damp soil, look at it under a microscope and you’ll probably find a few roaming about, using their ciliated mouthparts to scoop up bits of algae and other protists. They are particularly special, as not only can they survive radiation and other unwelcome environments by entering a form of indefinite dormancy, but they just don’t have sex.

Sure, we know of other organisms that reproduce asexually (essentially making clones of yourself) such as aphids, but most of thesehave sex at least some of the time. Of those who don’t, they have diverged fairly recently from their sexual ancestors, and so are likely to die out relatively soon. On the other hand, the all-female bdelloid rotifers don’t seem to have reproduced sexually for around 80 million years. This is a dry spell that deserves some serious attention.

It had already been known that these guys (well, girls) have a very clever way of repairing their DNA, which allows them not to be bothered by ionising radiation and means that they can repair any damage after coming out of dormancy. It was thought that this system could possibly be maintaining the genetic variation required. While this could still help, researchers at Imperial and Cambridge have discovered there is in fact a more understandable way of getting over millennia without a significant other.

Food. Eating a tub of ice cream is certainly one way of consoling yourself, but the bdelloidea do something rather special with their meals. They assimilate them. More specifically, they take the DNA from their food and incorporate it into their own genome. Which, by the way, is extremely cool.

Some nifty bioinformatics and analysis have shown that the proportion of the bdelloid’s genes that have come from other organisms (known as horizontal gene transfer) is around 9%. This is astoundingly high compared to other multi-cellular organisms such as the biologists favourite fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster – around 0.6%) or nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans – around 1.8%). What’s more is that these genes appear to havecome from the fungi, algae, protists and bacteria that make up the average bdelloid rotifer diet.

These genes aren’t just there by accident either; they have a strong effect in increasing the biochemical diversity of these creatures. Some of them code for some really important metabolic enzymes involved in processes such as glycolysis and carbon fixation, as well as toxin degradation and antioxidant generation. Some of genes encode for processes that aren’t elsewhere found in the animal kingdom, and now we know why. Stealing a link in the metabolic pathway of the fungi you are eating can certainly give you a novel advantage!

So, whenever you’re feeling lonely and the chocolate bar wrappers are mounting up, think of the humble yet awesome bdelloid rotifer. Unless you’re a member of the Borg, assimilation is sadly out of your reach. Of course, if you do manage to spawn life at some point and keep the gene pool nicely varied then you have no need to worry. If not, then you probably know what a Borg is.