A luxurious death

Alice Yang discusses whether fast fashion is killing luxury brands

Common knowledge to anyone who actually wants to embark upon a career in the near future, the world economy is dragging its feet along the ground and practically all global growth has been brought to a grinding halt. The unfortunate result from all of this, besides the lack of money each and every one of us is painfully aware of, is the negative commotion surrounding the luxury sector.

Investors around the globe have been worrying themselves to split-ends as to how much the slow down in emerging markets, especially China will effect the likes of Burberry and Hugo Boss, as well as PPR and LVMH – the corporate conglomerates that own high fashion favourites such as Louis Vuitton, Fendi, Givenchy, Marc Jacobs, Gucci, Yves Saint Laurent, Alexander McQueen, Balenciaga etc. And strangely enough, it seems that the answer the boards of directors have found themselves striving for is design more, make more and sell more FASTER. In other words, luxury seems to be taking a dive towards the world of fast fashion long trumpeted by the high street.

Take for example Hugo Boss: since appointing Claus-Dietrich Lahrs as CEO of the company in 2008, the brand has doubled the number of yearly collections it produces to four, reduced their overall development times and poured €100m into an automated factory. From the figures, this seems to have worked well for the company, with a year-on-year growth of 6% in its nine-month report this October, leading to a comfortable 12% share price rise this year. However, call me cynical, but does this not defeat the point of Hugo Boss being ‘luxury’? Surely, the premium paid on an item of Hugo Boss clothing as opposed to say, Zara, should be mainly due to the exceptional quality of the garment, its prestige and regrettably, in part, its name label. But once rattled down to the basics, of a t-shirt for example, I hate to admit it but the improved quality of the fabric itself no longer justifies the price hike given that both Boss and Zara items are factory made.

Moving onto an even stranger complaint, Nina Ricci’s recent additional collections also seem like a bad move away from their luxury high fashion roots. The design house now have not just the two standard spring/summer and autumn/winter collections, as well as the well popularised two pre-spring and pre-fall collections, but are now also hosting pre-pre-spring and pre-pre-fall collections. All in all, given that you trust my basic maths skills, that adds up to 6 collections of womenswear a year.

More explicitly put, in their attempt to attract more buyers with their diminishing price points per ‘pre’ added before the season, Nina Ricci seem to be heading down the road towards the fashion faux-pas land of A Little Bit Of Something For Everyone, otherwise known as Marks & Spencer. You see, the beloved British brand M&S fell upon its own arrow towards success when it stopped defining its customer base, and attempted to target everyone – in short, the company moved too quickly into unknown market territory, and is now sitting on a share price of just £3.79, down from £7.49 at its peak in 2007. And unfortunately Nina Ricci seems to be heading towards the same fate. Of course dedicated Ricci fans will still buy their girly dresses, but for those wanting something ‘special’, a bit of something that makes them feel above everyone else, which let’s not even TRY and deny is why many splash out on high fashion, Nina Ricci will no longer be the design house of choice.

Once again, I state my case: the definition and success of luxury rests on prestige and unobtainability. Once this is dissipated, it will not be long before we see an erosion in sales, and consequently profits.

Whilst of course there is a chance that I may be proven horrendously wrong, but, the way I see it, the trend towards fast fashion may be spelling out the final demise of certain brands. These brands are such that they are inaccessible enough at the moment to be termed ‘luxury’, yet are not quite topping the stable mountains of high fashion.

On top of this, there is also the issue of designers themselves. Peter Copping, in taking on 6 lines a year for Nina Ricci, may not be adding too much to his work load, but what about Alexander Wang who at the young age of 28 will now be designing 32 collections a year?

I kid you not, fashion’s favourite newbie, on being awarded the job of creative designer at Balenciaga, is now faced with designing more lines per annum than years he’s lived – four womenswear and two menswear for BOTH Alexander Wang and T by Alexander Wang; four womens and two mens lines for the bulk of his new job at Balenciaga; and 14 other lines (seven collections twice a year) making up the rest of the PPR-owned house. On top of that, there are also swim lines, lingerie, shoes, bags and jewellery to consider.

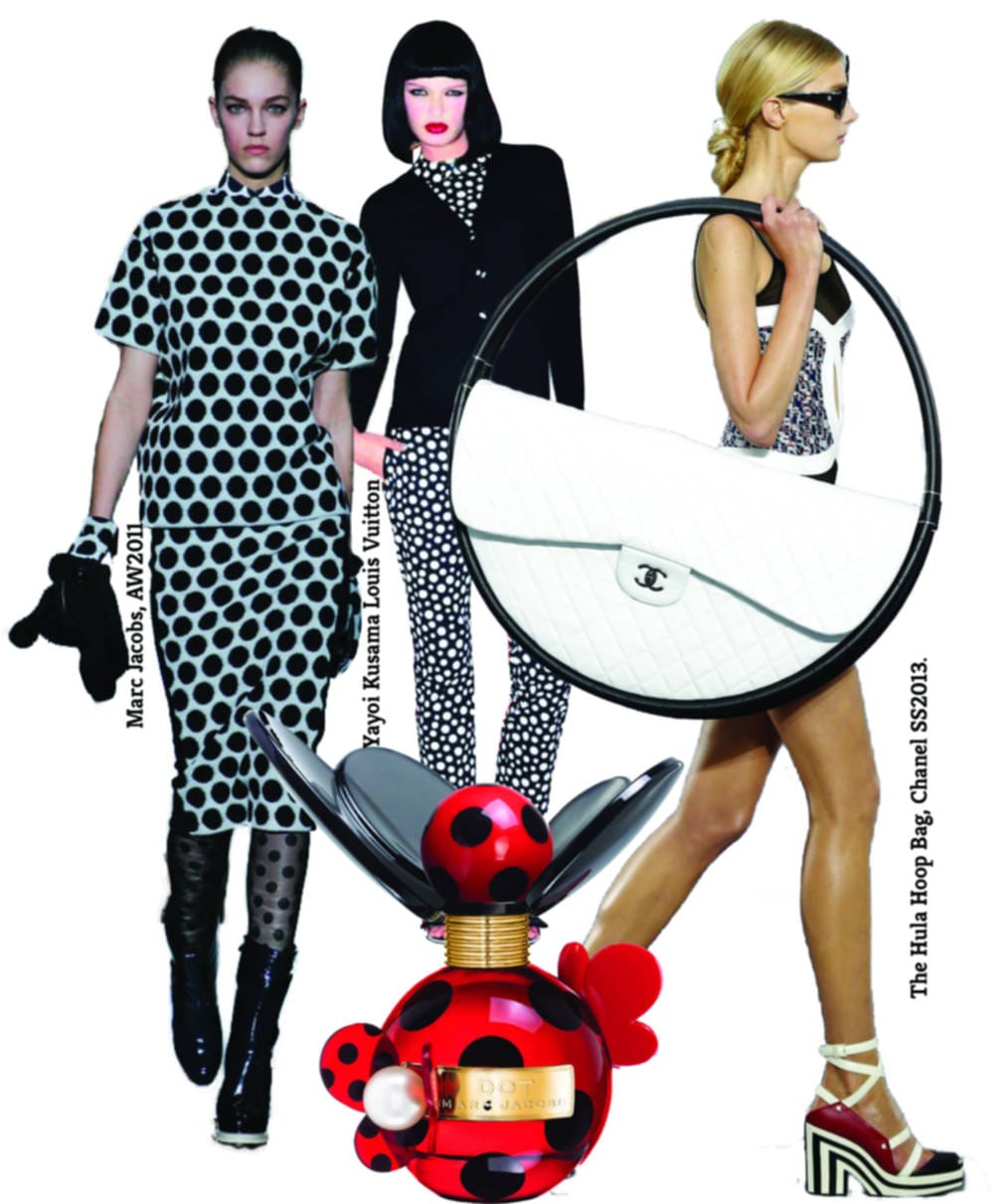

He may be young, and full of creative energy, but surely even Wang can’t pump out 32 new full sets of designs a year for long. And who can blame him if he fails, after all none of the old fashion guard have ever successfully taken on so much. In fact some designers, on reaching such a level of success, decided to go their own way: Jean-Paul Gaultier famously chose his own brand over Hermés, and Alexander McQueen too decided that his own label was to win attention over Givenchy. Even the multi-tasking masters of creation seem to be finally reaching the end of their creative ideas; Karl Lagerfeld’s designs for Chanel, Fendi and even his own eponymous label have been getting somewhat boring despite his outlandish attempts to spice things up (see Chanel’s SS13 hula-hoop bag), and even Marc Jacobs seems to be running out of ideas with polka-dots still not quite escaping his grasp (from Marc Jacobs AW11, to Marc Jacobs Dot Eau to Parfum and now alongside Louis Vuitton’s collaboration with Yayoi Kusama).

It seems that the recent onset of panic from investors and CIOs pushing for profits and margins seem to have completely demolished the lessons learnt from John Galliano’s fall from grace. But perhaps Wang and his fellow new generation designers will prove us wrong, and maybe, just maybe, this new world of fast fashion the high streets have been pioneering for so long might just turn out to be a success for luxury too. Whatever way the tides turn, the onset of the New Year looks like one to bring exciting new times a-plenty.