Reporting back on an extraordinary experience in Mongolia

Phillip Rodriguez, an English teacher, writes about his summer spent in Mongolia Summer Camp 2011

Terelj is located 60km away from Ulan Bator, the capital of Mongolia. The national park has smooth sloping valleys that climb up to become rocky peaks. This past July, the rains were plentiful. Grass carpeted the landscape, though not the soft type you’d find in your lawn. Rather the blades grew in little clumps with wiry roots that ran deep into the dry earth. The hardy vegetation provided an abundance of food for the horses, cows, sheep and camels that seemed to have free roam of the park. In sharp contrast to the green underfoot, a deep blue sky spread overhead with clouds so high they hardly seemed to move.

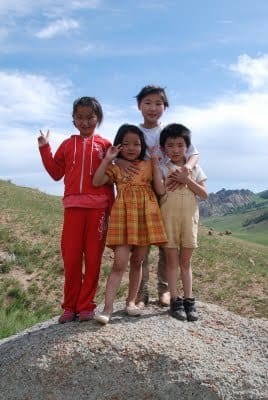

A narrow strip of pothole riddled asphalt carved through the park and about 10km from the entrance the road passed alongside our campsite. We volunteers arrived first. Twelve Singaporeans, a Mongol cook, a social worker, two translators, and myself. We had a day’s head start to prepare for the kids. When they came, the twenty-five little Mongolians shuffled out of their bus and made for the gers (tents). It took several minutes to get them settled down. Some fifteen minutes later, they were running amok exploring the camp. One boy hit another. Some tried to run off. The smaller children were crying. Our attempts to restore order amounted to nothing and the situation became more and more chaotic.

The children in the camp were not ordinary. They had been abandoned by their families, struck by misfortune, left to the vices of the street. The police had rounded the kids up and held them a shelter. That was where we picked them up for the camp. In their world, authority and rules were lacking. We tried to keep them under control. We had to. How else could we manage the camp? The first day eventually drew to a close and we volunteers returned to our gers exhausted. It is an understatement to say we were shocked by the children’s behaviour.

Day two: the situation got worse. The morning began with five of the boys disappearing from the camp. The group had hitched a passing car and returned to Ulan Bator. The police were brought in and they came down hard on the coordinators of the camp. It was several days until we heard from the police that they had made it back to the city, and in the time between, we were worried over their whereabouts. There was also concern that others might try to abandon camp. We took night shifts in the freezing Mongolian weather to ensure that children did not run away at night.

For classes, we broke the kids into two groups. I was in charge of teaching English. The twelve or so kids sat at a table while I scrawled letters and numbers on a white board. They repeated words and made use of their workbooks. To reward them I gave out stickers that Stephanie had brought. The ones they loved were those of Winnie the Pooh and his friends, but the prospect of getting a sticker was not enough to keep them focused. Some refused to do anything, others wandered off, and those that did try were easily distracted. I mixed in a few games to maintain their attention. Explaining the rules and giving a demonstration on itself should not have been much work, but with these kids it took a great deal of effort. That was how it went with everything. The simplest of tasks demanded our utmost energy. For example, when we took a group photo, all we needed was for the children to sit down and remain still for ten seconds. However, as soon as one boy took his place another would jump up, scratch his head and pick his nose. Even with fourteen volunteers, we had to shout, point and pull to get them to do what we wanted.

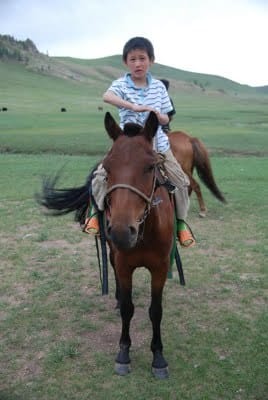

Horseback riding was the highlight of the camp. One of our translators, the young and affable Bilguun, had the local nomads bring their horses to our camp. We rented fifteen of the animals for two hours. They were the small stocky variety known more for their stamina than their speed. I went with first group. Many of the children were natural-born horse riders. They smiled, they cheered, and they laughed as they rode round the Mongolian countryside for the first time in their lives.

The great Genghis Khan has now been dead for over eight hundred years, but his legacy lives on in this country. Many of the boys bore his name, Chinggis, as pronounced in Mongolian. There was also a Temujin, the name the great Khan had before he became ruler. The other children in our camp had names that were harder to remember. There was Yataashk, Nemun, Babilguun, Sahnder, and so on. Since we failed to learn them right away we resorted to using nicknames. In the case of Sahnder, we called him ‘Carry Me’, because the boy went up to all of the volunteers and said those exact words while reaching up with his arms. And then there was ‘Horny Boy’ who had an affinity for the female volunteers and their womanly parts. Looking back, I might think it humorous that we called him that had I not known he had spent time on the streets hanging around prostitutes and pimps. It was that past that shaped him.

Sadly, the other children’s pasts were no better. The boy Temujin had lost his father in a car accident. As a result, Temujin’s family fell apart and his mother being unable to care for him, abandoned the boy. The siblings Pagma and Khan-tseg-rik, only four year olds, had been sent out by their aunt to beg for money. When the police caught them, the aunt refused to take them back. The authorities did what they could to place street children with relatives or in foster homes. I guess you could say the kids were broken, but if they were, they had grown resilient and strong with time. I’d seen it a hundred times over. As much as they fought with each other, scraped up their legs and cried, they always bounced back with a smile.

In time, some of their good qualities surfaced. The 14 yr old boy Temujin was special in that he had a strong sense of propriety. Though he was a little fat and geeky, the other children did as he said. It was a respect that came from the care he openly gave. It could be something as simple as helping the others going to bed. The little ones needed that.They had no mother to tuck them in. No brother to lean on. The older children took on the roles of brothers, sisters, mothers and fathers. This was the world they came from.

The real darling of the camp was Tengis. He was a small boy with sandy brown hair, cherub cheeks and curious eyes. He certainly had cuteness in his favour, but it was his carefree, happy attitude that won us over. He was mostly smiles and giggles, evenfor no apparent reason. Incidentally, his birthday coincided with the camp. We celebrated in the kid’s tent. Rather than a cake, Tengis received a chocolate pie with a single candle sticking out from the center. Sitting at the head of the table, he looked down and his brown eyes sparkled bright as the moment took hold in his heart. The tears came and we realized then it had likely been the first birthday party anyone had thrown for him

In retrospect, I can now say that the children were all unique and special in their own way. I could write on and on about each of them. Like how we mistook the boy Chingu for a girl and did not realize our folly until one of us noticed he was peeing standing up.We simply assumed he was a girl because he had long hair, but young boys in Mongolia are like that. They get their first haircut at the age of four. Chingu got his a little earlier because we discovered he had head lice. As we cut off his locks with a pair of dull scissors, he beamed proudly, having entered the next symbolic stage of his young life. The other children who had lice reacted differently during their haircuts. They cried and pouted, and no amount of candy or comfort could appease them.

For a week, we spent roughly twelve hours a day with these children. The volunteers were sun burnt and sick from the weather, and our energy was exhausted. I admit I too was getting burnt out. I wanted to get back to the capital, have a hot shower, wash my clothes and drink myself in to a stupor. It would have to wait.

Our last full day at the camp was particularly rough. We had exhausted most of our ideas for activities and there was far too much free time for the children to run around. Dinner was poor as we were finishing the last of our food.

After dinner, we had a final meeting with the kids. Stephanie had originally lied to the children that the camp would continue for several more days. She did it so they would not try running away, because the consensus was that none of them wanted to return to the shelter where they were often bullied by others and occasionally mistreated. When Stephanie admitted the truth the children seemed a little disappointed. She quickly shifted topic and handed out postcards to write on. These were meant as thank you letters to the many people who had given donations to make the camp possible. Next, the children wrote comments on a different slip of paper thanking the volunteers.

The first child to cry was Sahnder. He dropped his head, his shoulders shook, and he drew in short breaths. A volunteer walked up and held him from behind. Others soon shed their tears, and the whole tent became drowned in sniffles and sobs. Some children would sit in a corner and sob, while others would wail openly. Through their choked up voices, the children said things to us. We had to get one of our two interpreters to repeat their words in English. Temujin told me he did not want me to leave him. He said he thought of me as a father. I looked at him and shook my head. I had my own life to get back to and told him as much. The words rang true for each volunteer. We could only give the children so much.

The following morning the bus came to take us back to the capital.We shuffled in, took our seats and the engine started up. The drive back took a little over an hour. Green, treeless swaths of land gave way to muddy earth studded with gers and shanty houses. Concrete soon filled in the edges of the road, and we came to a stop next to the welfare office near the city center. The children went in to another shuttle bus bound for their shelter while we were free to find our hostel. It was a short goodbye.

We had given a group of street kids the opportunity to enjoy things they would never have had the chance to enjoy. It was an experience, and how they choose to learn and identify with it will influence their young and impressionable lives. Perhaps that is only wishful thinking, but looking back I feel a strong fondness for the children and the times we shared. For both volunteers and children, it was a crazy, wild and unique series of events that unfolded in the hills of Mongolia. And beneath it all, there was the laughter, the smiles and the desire to do something good and meaningful.

For that much I am grateful.

Interested in volunteering for Mongolia Summer Camp 2013? Contact David at weiyu.tan10@imperial.ac.uk