Genes affecting intellect

Your academic success could be down to your genes

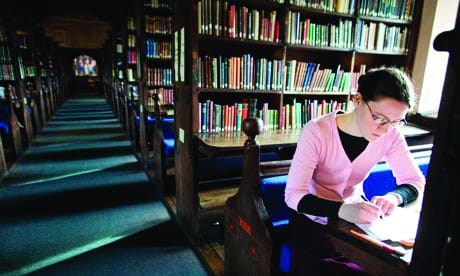

Imperial students fall generally into two categories: those who work hard and those who don’t work at all. Students across all years either diligently trek to the library every evening or pass it completely (as in, walk awkwardly around the redundant new library porch) to go straight to the Union.

However, when it comes to academic success, there seems to be no such correlation. Blame your department, blame your note taking skills or even blame the annual arrival of the American girls tempting you into the depths of Metric, but new research has shown your academic floundering or success could be down to your genes. A paper published online in Nature this week has taken the first step in actually quantifying how genetics can influence cognitive ability, but take their findings with a pinch of salt - intrinsic aptitude alone won’t get you that 2:1.

The study lead by Ian Brady, a professor of Differential Psychology at the University of Edinburgh, has allowed an insight not just into intelligence causation but also intelligence degeneration over time, thanks to data uncovered from the early 20th century that was collected across Scotland. Using a traditional cognitive testing method in conjunction with high tech genomic sequencing, test scores from a group of unrelated individuals were recorded at two distinct times in their lives, and then compared against the genetic variation between the groups.

The test used was the Moray House Test (not that House), and is very similar in structure to entrance tests usually taken for Grammar school entry by 11 year olds, sometimes referred to as the 11-plus. A combination of verbal reasoning questions were asked to just under two thousand participants aged 11 back in 1932 and 1947, and the same individuals were tracked down when they were aged 70 to take the same test under the same standardised conditions. They also gave a cell sample to determine how strong the genetic link may turn out to be.

Their genomes were then scrutinised to produce Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) data. SNPs are particular points in the genome sequence where one fraction of the species population has one nucleotide type, and another substantial fraction has another type. SNPs therefore can be used to give an insight into the possible genetic causes of varying characteristics between individuals in the same population, in this case intelligence. Over half a million SNPs were scrutinised for every individual who took the test, and Brady was able to put forward the estimate that 24% percent of their cognitive ability is determined by the genes due to the differences in the scores between the two age groups.

So does this mean that about a quarter of our intelligence is genetically determined from the start? Not necessarily, as the overall statistics are a bit sketchy and the Moray House Test is just one of many ways to test intelligence, so a greater, more detailed study may be needed. A greater genetic insight is needed too, such as locating specific gene sequences, but this research does provide a new understanding on which to base future neurological studies into intelligence and its causation.

However, if 24% of your intelligence is actually genetic alone, that means that 76% is still down to you. This should come as great news to all those who spent Christmas revising hard and neglecting their family, their friends and their hygiene, as you may actually stand a chance of doing well. To everyone else, put down Felix, finish that Nonogram later and sulk over to the library. You may have to attempt to work hard after all.