Truth, lies and tall tales about “Work for your Benefits”

Stephen Smith conducts an in-depth investigation of the Workfare scandal. Is it really forced labour? Who is benefitting from it? And what is our government doing in our name?

A spectre is haunting our futures – the spectre of unemployment. Most of us are soon-to-be graduates: some of us, inevitably, are the soon-to-be unemployed. With every month, increasing numbers of young people are finding themselves jobless, and increasing numbers are turning to the government for support.

But what kind of support do they receive? The “Work for your Benefits” scandal has flooded the media with allegations and insinuations about the government’s treatment of the unemployed: is it supportive help or slave labour? As graduation day approaches, we all need to be aware of what is really going on; we need to be prepared for when unemployment comes for us.

A case study: Cait Reilly

You might be familiar with the story of Cait Reilly, an unemployed Birmingham University graduate who wanted to be a curator. Jobless for 18 months, she eventually managed to find unpaid work in a museum to gain experience while looking for a paid job. But a museum was not good enough for the government: she had to cancel the work and take up “training” at Poundland instead, or lose her £53 per week Jobseeker’s Allowance.

“It was not training, but two weeks’ unpaid work stacking shelves and cleaning floors,” she wrote in the Guardian, “I came out with nothing; Poundland gained considerably.” Her story started a wave of popular disdain for what has come to be known as “workfare”.

As part of its [Get Britain Working](http://Get Britain Working programme) programme, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has introduced new work experience schemes for the unemployed “which aim to fight poverty, support the most vulnerable and help people break the cycle of benefit dependency.”

But critics argue that the reforms are nothing more than forced labour, that they exacerbate unemployment and that they provide corporations with free work paid for by the taxpayer. “We were doing exactly the same work as the paid staff,” [said Reilly](http://said Reilly), “If the Government subsidises high street chains with free labour, they don’t have to recruit. It causes unemployment rather than [solving] it.”

Reilly has become a divisive figure: a hero for those on the left, a [lazy elitist](http://lazy elitist) to those on the right. But for all its emotional power, the truth behind her story has remained elusive. In her own article in the Guardian, Reilly stresses that her work was compulsory, “I thought the ‘training’ was optional, and it came as a shock to be told I was required to attend;” but the government’s website for sector-based work academies (the scheme in which Reilly was made to participate) clearly states “taking part is voluntary”. So which is it?

The government seems to have made finding the answer to this question rather challenging. Unlike other aspects of Get Britain Working, the sector-based work academy schemes seem to have no formal regulations (or if they do, they are not publicly available).

But it is possible to find regulations: simply a matter of discovering an obscure inter-departmental memo from 15 June 2011 stating that, “Service Academies ... should now be known as sector-based work academies.” Now, Service Academies do have formal regulations (though they are a challenge to find) and they make for interesting reading.

“The decision to participate in a Service Academy will be voluntary” according to the regulations, but, “once a claimant...has opted to participate in a Service Academy, taking up the place and attendance on the training becomes mandatory.” You can agree or disagree to a work experience placement, but if you agree you are not allowed to change your mind.

It sounds like Cait Reilly was the victim of a very unfortunate misunderstanding. Her adviser rightly told her the training was optional, but neglected to mention that she would have to stay for the entire training period if she agreed to it. Moreover, in her Guardian article, Reilly claims she was told the training would last for one week, rather than two: one week would have been fine, two weeks forced her to quit her museum job. Her adviser’s stupidity cost her her job and, quite possibly, spoilt her chances of ever becoming a curator.

We might reasonably ask why Reilly was offered the training at all. According to the DWP, “sector-based work academies are one of the services that Jobcentre Plus offers to help you get back into work.” But clearly Reilly’s job at the museum was more practical than a Poundland training scheme, especially given that she “already had retail experience,” as she claims. Presumably her careers adviser simply forgot to take this into account.

Who, then, is at fault? If we believe the right-wing press, then we must blame Cait for complaining at all, but in truth Cait was completely right to complain about her dreadful treatment. If we believe the left, then we must blame the government for having this scheme in the first place: understandable, but again wrong. The blame can only be left with the careers adviser, and her employers.

The fact that Reilly’s adviser evidently caused her suffering raises the question of how much power advisers actually have. What do they have the authority to do, who do they work for, and are they accountable when they make mistakes?

Forced labour or not?

The DWP’s Get Britain Working homepage is a chaotic mixture of various overlapping schemes, programmes and initiatives. Aside from Reilly’s sector-based work academies, the government also offers two other alleged “forced labour” schemes: Work Experience and Mandatory Work Activity (MWA). These are the source of a lot of the popular anger about the Get Britain Working programme, and, as with many things that cause anger, they are not fully understood.

Writing in the Guardian, John Harris said of people on Work Experience schemes, “they can refuse to take part or pull out during the first seven days, but thereafter the work becomes compulsory.” This is not quite true. Benefits can, in fact, be removed from any job seeker who, “has, without good cause, neglected to avail himself of a reasonable opportunity of a place on a training scheme.” In other words, if your advisor suggests a Work Experience scheme and you refuse it, you risk having benefits stopped for anything from one week to six months.

But fear not! There is a way to avoid Work Experience: you must first agree to it, then attend the first meeting, and then within seven days you must tell your adviser in writing that you wish to leave the job. Simple! Not only is Work Experience rather more punitive than John Harris claimed, but it comes with a prohibitively complex set of regulations that take a lot of time to understand: it must be easy to get caught out by them, and get punished as a consequence.

The Mandatory Work Activity schemes are altogether more controversial. “Where advisers believe a jobseeker will benefit from experiencing the habits and routines of working life, they have the power to refer them to a four week placement,” according to the Department for Work and Pensions. But according to John Harris, “people are forced – via the threat of their jobseeker’s allowance being suspended – to put in 30 hours a week doing work.” Again, rhetoric about MWA is everywhere but facts are harder to come by.

The content of these schemes is very like Work Experience, the real difference is in the sanctions for failure. A job seeker cannot choose whether or not to participate in the scheme, it is aimed at those who lack the motivation to voluntarily take part in Work Experience. If you refuse the scheme, you lose 13 weeks’ JSA; if you miss a day of work, you lose 13 weeks’ JSA; if your supervisor is dissatisfied with your performance, you lose 13 weeks’ JSA. If you fail your Mandatory Work Activity twice then the penalty increases to 26 weeks. And if the Welfare Reform Bill becomes law, a triple failure at MWA will cancel your benefits for 3 years.

If 26 weeks with no income (and presumably no food or shelter) were not bad enough, note that there is no way to appeal against the decision, even if you believe the punishment to be a mistake. The only way is to take the government to court, a high-stress prospect, even worse at a time when you have no money to pay for travel or a lawyer.

If you are able to demonstrate “hardship” then you may be able to keep your benefits, but in the MWA regulations the definition of “hardship” focusses almost exclusively on those who are severely disabled, pregnant, or with young children. There is little hope for an able-bodied, childless job seeker.

It is disconcertingly easy to describe all three kinds of work experience as “forced labour”. In the case of MWA, the work is genuinely forced; the other cases provide ways of avoiding the work, but the regulations are so unnecessarily complicated that knowing how to quit is a huge challenge in itself. I believe it is likely that the government made the regulations complex on purpose: this way they can claim the schemes are voluntary, while in practice they are not.

The advisers’ authority is also worth questioning. In all these cases an adviser has the power to force someone to work, even when, as with Cait Reilly, the work spoils their future prospects. The MWA regulations tell us where this authority comes from: the power to force someone to work “may be exercised by, or by employees of, such person (if any) as may be authorised by the Secretary of State.” Up until now, I had believed that the advisers were employed by the state as civil servants: I was wrong.

The Job Centre Myth

In the popular imagination, Jobcentre Plus is a government agency and its careers advisers work for the government. For example, Jim Murphy, a lawyer who has been very critical of the Get Britain Working scheme, said that it “amounts to exploitation, decided at the whim of a Jobcentre Plus adviser.” None of this is true. In fact, as of last year, Jobcentre Plus doesn’t even exist at all. It is now merely the public face of the DWP.

In its place are a series of private employment consultancy firms. In London, for instance, the MWA is provided by a company called Seetec, in the South East by A4e. A4e has a particularly bad reputation. On Monday, the Mail published an article stating “Labour MPs claim A4e’s record on finding people jobs is ‘abysmal’” and demanding that Emma Harrison, the head of A4e, should stand down. It seems that while Harrison was in charge of A4e, she was also advising the government on its Get Britain Working programme. Presumably not just an innocent coincidence.

Nor is Seetec scandal-free. According to the unemployment rights blog Intensive Activity, Seetec do not provide refunds for travel expenses, though they are obliged to do so in their contract. MWA participants in London, then, are forced to choose between losing all their JSA, or spending it on transport to and from their compulsory work. A weekly London bus pass for a JSA recipient is £9.40: for an unemployed young person, this reduces total weekly income to around £44. MWA therefore makes life extremely uncomfortable for a jobless young Londoner.

It is worth remembering that the careers advisers mentioned above are employees of these companies. They have the authority to make someone take up Mandatory Work Activity, and therefore the power to cause serious suffering to an individual whenever they so desire. Being private contractors, they are accountable to no one but their managers, and there is no formal means of complaint except, of course, through the courts. It is impossible, then, for even the Secretary of State to sack a bad adviser.

The MWA contract between the government and Seetec is available online, and it includes a clause stating that Seetec (and presumably also the other companies) are paid according to how many people they get onto MWA. Peraps advisers would force job seekers into MWA in more situations than necessary, just to make more money. After all, making money is what private companies do.

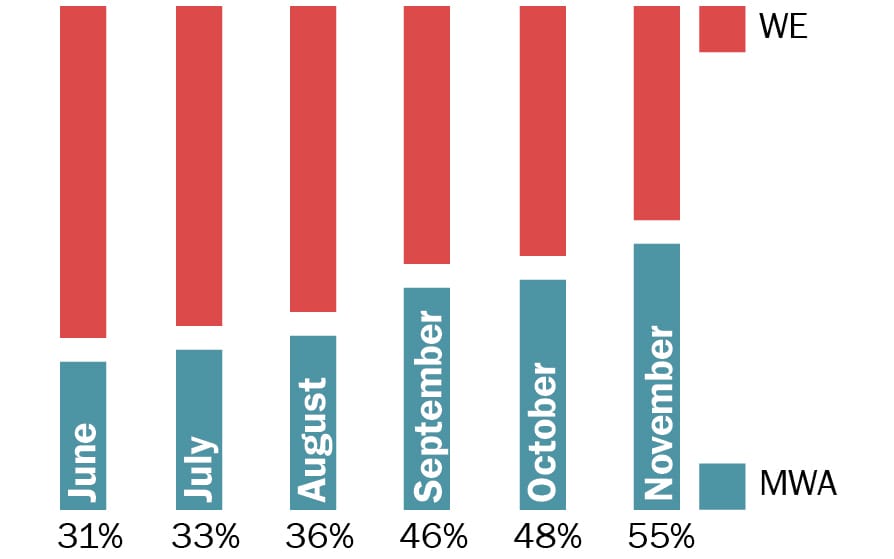

Government statistics released this month (see above graph) show that the ratio of MWA to Work Experience participants – a ratio we would expect to stay roughly constant – sharply increased in September and again in November; funnily enough, September was the month in which Jobcentre Plus started being replaced by private employment consultants. The joys of privatisation...

Given all the above, I think it is fair to say that the switch from Jobcentre Plus to private consultants was a bad idea. There is the corruption at A4e, the illegal behaviour at Seetec, the very high possibility of unnecessary forced labour, and the unaccountability of the advisers, and all of this just since September 2011. Conservatives... What will they do next, privatise the NHS?

Who benefits?

All premeditated crimes have motives, and the same can be said for the Get Britain Working programme. Who benefits? There are at least five parties to consider: the job seekers, the government, the taxpayers, the employment consultants, and the corporations. All could lose or gain from the work experience schemes; looking at who gets what might enlighten us to the truth.

First, the job seekers. The scheme is intended to help them, as the Department for Work and Pensions says, they mean to “fight poverty, support the most vulnerable and help people break the cycle of benefit dependency.” But the latest unemployment figures reveal 8.4% unemployment, which rises to 22.2% among 16 to 24-year-olds, and unemployment is rising all the time: so the work experience scheme will not have an appreciable effect on youth unemployment. It is arguable that the jobless are gaining skills for their CVs for when the recession is over; but this argument must be set against the fact that job seekers are being forced to work for under £2 per hour. I think we can confidently say that, except in perhaps a few circumstances, job seekers do not benefit from the scheme.

The media and (to an extent) public hysteria about “benefit scroungers” was fairly ubiquitous in 2011; the Daily Mail’s infamous Jan Moir, for example, said of Cait Reilly, “nobody owes this girl a living. Least of all those who work.” Then, Get Britain Working probably seemed like it was working for the government. Now, however, the same Daily Mail has criticised the government’s handling of the scheme, and on top of this there are public protests and suggestions that the government wants to return us to Victorian Britain. As yet there are no reliable polls on the matter so it is hard to tell, but I would guess that the weight public opinion is against the government in this case: they thought they would benefit from the scheme but they haven’t.

If taxpayers benefit from the scheme it can only be because fewer people are accepting Jobseeker’s Allowance, either because they have returned to work, or because they have had their allowance removed as punishment. Unemployment is rising, and has been for some time, so the former cannot be true. As for the latter, it is impossible to tell how many people have been punished, since the published statistics are so minimal they could hardly be called statistics at all.

We do know, however, that 24,010 people were referred to MWA between May and November 2011. If we assume that 10% of these were punished and lost their benefits for 13 weeks, the government will have saved about £2 million, a negligible quantity. Since MWA is the most punitive and the most used of the three work experience schemes, we can guess a total of about £6m gained from the work programme in 6 months. The taxpayer, then, can hardly be said to benefit.

Comparatively, employment consultancy firms must adore Get Britain Working. Not only does the privatisation of Jobcentre Plus provide companies like Seetec and A4e with very lucrative contracts, but the government is a customer which can (hopefully) never run out of money. There is no doubt that these companies benefit greatly from the programme.

With corporations it is a much more complex story. Let us take Tesco, for example. At first, they benefited slightly from the scheme: for each MWA placement, they got 120 hours of labour for free. That’s £730 saved per person, at minimum wage. But Tesco is a vast corporation, so the amount of money which they saved in this way is negligible.

Recently, however, Tesco has suffered from serious public anger. After an advert was placed on the Jobcentre Plus website advertising work at Tesco in return for Jobseeker’s Allowance, thousands of angry consumers attacked Tesco’s Facebook wall threatening to boycott the company until they stopped employing MWA participants. Soon afterwards, angry campaigners staged a protest at a Tesco store in Westmister, forcing it to close.

Over all, Tesco has not benefited from Get Britain Working, and the same can be said, though to a lesser extent, of the other participating corporations.

Stupid or evil?

We are left, then, with a government scheme in which the only beneficiaries are private employment consultants. Although, were it not for the unanticipated public anger, the government and some corporations would have benefited also. Job seekers, for whom the scheme is allegedly designed, come out worse off over all.

Which leaves one question: is Get Britain Working a very poorly designed scheme or a cynical attack on the unemployed? I know which side I come down on: government advisers are surely not stupid enough to unintentionally create such a dreadful programme.

What we have here is a nasty scheme which punishes the unemployed and benefits only a few companies; which puts power into the hands of unaccountable advisers, and pays them to abuse it; which has the ability to totally ruin the lives of those it is explicitly intended to help. But it is a scheme which many of us may soon have to face.

As graduation day approaches, and youth unemployment rises, the Jobseeker’s Allowance looks like an increasingly likely possibility. But we must be wary: this is a programme designed to trick the jobless, not help them. From the moment we graduate, we could all be Cait Reilly.

A fully referenced version of this article can be found at rustylight.blogspot.com