God’s Coming – Look Busy

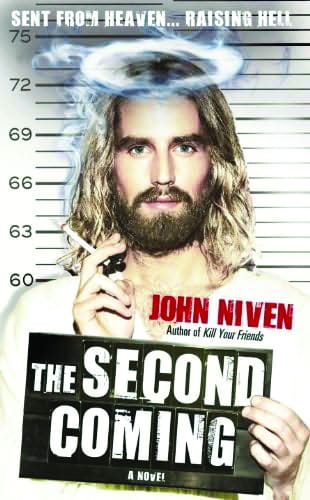

John Niven’s religous satire fails to impress

“GOD’S COMING! – LOOK BUSY!”

“Shit. Think He’s is gonna be pissed?”

And so begins John Niven’s fourth novel, The Second Coming. Niven introduces us into his world as God returns from his one week vacation – a week in Heaven corresponding to several hundred years on Earth. God, who left for his vacation at around the time of the Renaissance, returns to find his lovingly created planet scarred by “Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Belsen, Guantanamo, Belfast, Cambodia, Vietnam, Flanders, Ypres, Nagasaki, Hiroshima, Rwanda, Bosnia……ethnic cleansing, capitalism, communism...nuclear deterrence and mutually assured destruction…Fatwa and Jihad….gays being hanged…the Taliban…the burqa and the hijab…Kim Kardashian…deforestisation, globalisation, collateral damage, brand awareness, marketing, product placement and Republicans”.

However, this is no ‘normal’ God. As Niven gleefully tells us, this is a God that “loves fags”, “loves spades” and has his “shirt sleeves rolled up” to tackle the big problems of our age (like a celestial David Cameron). This is a God that conference calls his fellow religious entities (complete with a potty mouthed Muhammad) and has dinner with Satan – the two have a friendly competition going about who can get the most admittances into their respective domains, and a God that accidentally starts the big bang because of a casual “morning toke” gone awry. So far, so deliberately controversial.

Niven does not stop there. When God is meeting Satan for dinner, we are greeted with a parade of celebrity and political hate figures meeting numerous grisly ends: you have Reagan crapping himself to death and the recently deceased Jesse Helms. Helms was, before his death, a five term Republican senator for North Carolina, who was famous for opposing civil rights, disability rights, any bill that he suspected of hiding vaguely feminist tendencies, gay rights (he once famously called one of his many political opponents a “militant-activist-mean lesbian”), affirmative action, contemporary art that he considered to be sexually inappropriate, and (of course) abortion. Helms meets his sticky ending by the hands of Satan, whom “slashes Helms throat” causing him to “topple over in a spray of blood”, after Helms had just admitted his love for “COCKS! GIANT BLACK FUCKING COCKS!” After witnessing the roaring trade Satan is achieving, God decides to send the “little bastard”, or Jesus, back down to his earthly home to clean up our collective moral debris.

Jesus is reborn as a struggling front man of an indie group, his fellow band members being a wholly ‘unique’ blend of vapid, two dimensional characters. In a bid to spread his new commandment of “Be Nice” to the masses, Jesus enters American Popstar – a reality show that searches for the next big thing. And of course it is headed by Steven Stelfox, Niven’s deliberately unsubtle recreation of Simon Cowell.

...he portrays all of his arguments in exceptionally simplistic, Tabloid-esque headlines with the intention to shock...

It is within these segments of the novel – the ones that deal directly with the music industry – that gives the novel its only redeeming feature. It is hard not to be swept along with the genuine enthusiasm the author has for the concept of Jesus playing ‘Born to Run’ on the final of American Popstar. However, for some reason, Niven suffocates these moments of agile and authentic humour with clunking pieces of synthesised angst about just about everything. And this is what proves terminal for the novel.

As you may have noticed from the above extracts, this is a book that doggedly chases controversy. Henry Sutton, a journalist for the Daily Mirror, said that “only the truly ignorant will take offence” to Niven’s novel. I would agree with that statement – this book is not offensive. However, the book is incorrect. Not politically incorrect but just completely incorrect.

Niven aims his tirade of artificial moral disdain at almost every aspect of organised religion. He does not consider the fact that the characters he chooses to represent organised religion are realistic. For example, the Pastor in the novel is an obviously homophobic, racist, misogynistic and sexually repressed individual. Not once does Niven reflect the debate that is present inside the church regarding topics such as gay marriage; instead, he decides to depict the argument using only primary colours. He takes a shot at the celebrity culture we live in, yet does not decide to dissect the anatomy of such a culture. Niven also criticises the burqa – but again chooses to ignore the existence of the many women who choose to wear the burqa for their own personal reasons. In doing so, Niven ignores the inherent beauty of that decision – the kind of decision that even the God Niven depicts would agree with and thus misses the point quite spectacularly. Thus, he portrays all of his arguments in exceptionally simplistic, Tabloid-esque headlines with the intention to shock, polarise and, childishly enough, probably to offend. And it is this that proves to be the worst part of a pretty distasteful book. How can Niven credibly criticise organised religion, republicans etc. etc. of making over simplistic, illogical, unrepresentative and essentially bigoted arguments when he himself makes over simplistic, illogical, unrepresentative and essentially bigoted arguments? To put it another way, I am not criticising Niven for pointing out the plank of wood in his brother’s eye when he has dirt in his own – I am criticising the fact that they’re brothers in the first place.

Or to put it in a way Niven may understand, only buy this book if you want to fork out £7.99 for a roll of toilet paper with only 376 sheets.