Honey bees seek thrills just like us

Scientists have investigated differences in bees' neurochemistry determining the way in which they forage for food

Honey bee scouts are at the forefront of bee exploration, seeking out new sources of food for the hungry hive and finding suitable nest sites for the colony when it outgrows its current home. These bees differ from their fellow foragers. They do not wait to be told where to go or what to do, but seek novelty, maybe even adventure.

A new study, published in Science, has examined the brains of honey bee scouts and found that this novelty-seeking behaviour appears to be based on the same molecular pathways used in similar thrill-seeking human behaviour.

Novelty-seeking behaviour in vertebrates involves catecholamine, glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric (GABA) signalling in the brain. The differences in thrill-seeking behaviour between individuals are often attributed to personality differences. So do insects like honey bees have personalities of their own, just as we humans do?

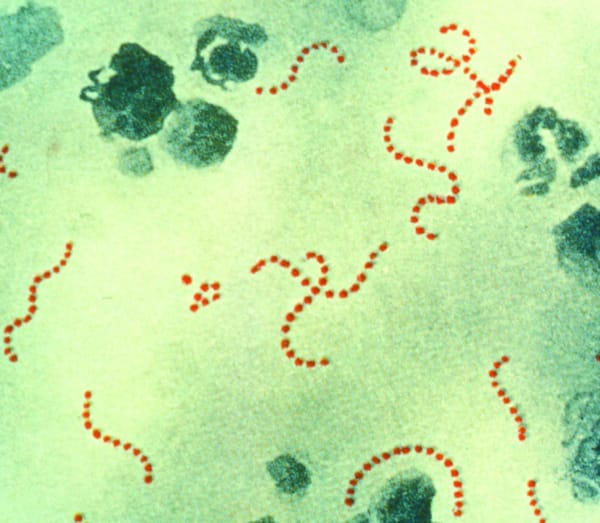

The researchers, led by Gene Robinson and Zhengzheng Liang, compared the molecular underpinnings of novelty-seeking behaviour in bees that do and do not scout. The bees in the colony under scrutiny were fed from a jar of sugar water with a yellow flower pattern and faint scent for a few days. On three consecutive days an alternative jar with a different colour and a different scent was placed in the hive’s vicinity. Bees that visited at least two new jars were defined as scouts and marked by Liang, for later capture.

Microarray analysis was performed on the brains of these scouts, and on the brains of non-scouting bees, to determine the activity patterns of genes in each. Among the thousands of differences in gene activity that the researchers found between scouting and non-scouting bees – around 16% of 7500 genes in total showed a significant difference – several were related to the signalling pathways implicated in vertebrate novelty-seeking, including receptors for the neurotransmitters glutamate and dopamine.

As both scouts and non-scouts forage for food, Robinson and his colleagues were surprised by the magnitude of differentially expressed genes between the two. In order to determine whether changes in brain signalling caused novelty-seeking behaviour in the bees, they were exposed to different treatments that would activate or inhibit the neurochemical receptors involved in the signalling paths implicated in vertebrate thrill-seeking.

The researchers found that octopamine and glutamate treatments increased the likelihood of scouting behaviour in bees that had not previously shown novelty-seeking behaviour. Bees that were fed chemicals that blocked dopamine receptors were less likely to exhibit scouting behaviour.

Since honey bees and humans are not closely related, novelty-seeking behaviour has presumably evolved independently in each lineage. But the results suggest that insects, humans and other animals share a “toolkit” of genes that plays a role in this type of thrill-seeking behaviour. This kit has been adapted for use in each species, but it still contains the same components. Perhaps the pioneers of our world, be they human astronauts or honey bee scouts, are not so different after all.