Plutonium found far from Fukushima

The Fukushima disaster has resulted in a wider spread of radioactive material than anticipated

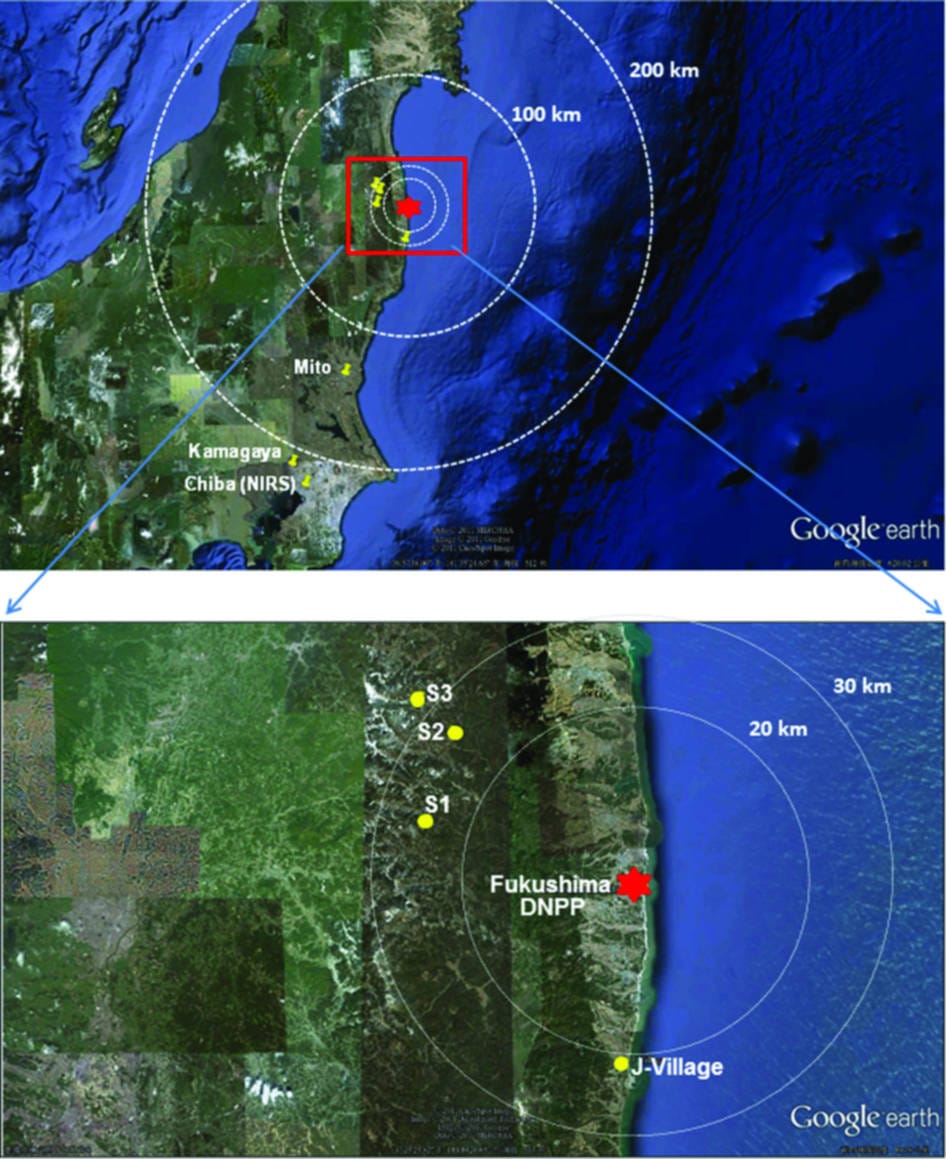

Last week, just days before the anniversary of the Fukushima disaster, came evidence that radioactive plutonium has spread much further from the nuclear plant than previously thought. Scientists from the National Institute of Radiological Sciences in Japan, found traces of the potentially harmful substance over 20 kilometres away from the plant – thankfully though, they say this poses no health risk.

The crisis, which left 27,000 people dead or missing and caused billions of dollars in damage, began on 11 March 2011. A magnitude 9.0 earthquake on the Pacific floor triggered a tsunami which impacted, and subsequently devastated, the northeast coastline of Japan. Moments after the initial quake, the three operating reactors at Fukushima Daiichi automatically shut down. However, 41 minutes later the tsunami burst through the plant’s defences, flooding the reactors. Over the following days, emergency systems failed and the reactors melted down. Hydrogen gas was released, triggering explosions in the reactor buildings which allowed volatile radioactive chemicals to escape into the air and sea.

Unlike other radioactive contaminants to come from Fukushima, plutonium is different. It is not volatile so it is harder for it to escape from a nuclear reactor during a meltdown. But it is thought, in the case of Fukushima, the force of the hydrogen explosions propelled out some plutonium in the form of particulate matter.

Plutonium can be extremely harmful. When it decays, it releases heavy particles such as electrons and helium nuclei – not particularly dangerous outside the body, but if ingested can cause genetic damage. The team analysed soil samples for different plutonium isotopes produced during the course of the power plants’ nuclear reactions. And for the first time, detected traces of plutonium-241, which has a half-life of about 14 years.

The additional plutonium exposure from inhaling this loose plutonium is five times higher than the government’s current estimate for exposure from the accident. But the health risk is less scary than you might assume, as the average person on Earth receives much greater exposure over a 50 year period from natural sources of radiation.

Lead author of the study Jian Zheng estimates that the total amount of plutonium-241 released from Fukushima was about 10,000 times less than that from the 1986 Chernobyl accident in Ukraine – making these recent findings particularly interesting. The distances at which the plutonium was found suggest that it was ejected during the hydrogen explosions in the first days of the crisis yet the relatively low levels indicate that the heavily shielded concrete casings around the reactors did offer protection from the worst of the fallout.

Independent work such as this is particularly important because, as reported in Nature last week, mistrust in the government in running high among Japanese residents. And although clean-up of the immediate site could take four or five decades, studies like this are key for providing residents and evacuees with the information they need to get their lives back to normal.

DOI: 10.1038/srep00304