Don't regress into despair

The joy of stats (and patience) in a scientific world

For anyone considering a career in biological or medical research, the old catchphrase “Never work with children or animals” often comes into play. Biological data never quite does what you want it to. Sometimes a scientist’s intuition, or even looking graphs of your data, tells you that the trend you’re looking for does exist. But now the question is, how can one get the statistics to prove it to the rest of the scientific world?

This dilemma has troubled many a biology student over the course of time. There is nothing worse than the feeling of despair, after spending many weeks in the lab, or out in the field in the heat, rain or cold, to come to analysing your data and to discover that the result is...nothing. But with biological or medical data, this is often invariably the case.

There are many reasons for this. Firstly, animals, plants and people are affected by a multitude of complex factors that all interact with each other. Even if you have an idea of the main factors that may be affecting your results, and you measure these, it is impossible to measure every single factor, and account for every single bias. But statistics is a wide field, and there are some interesting statistical tests out there which can be very useful to biologists.

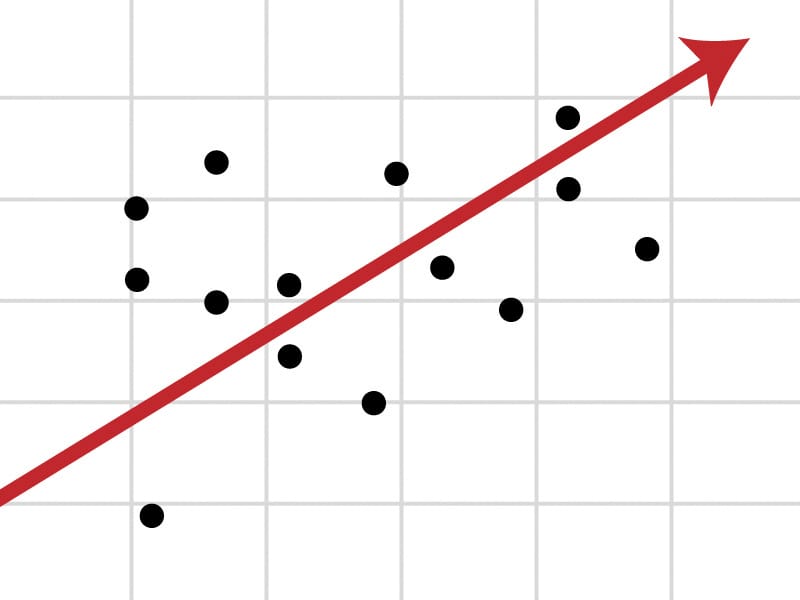

Quantile regression is a test that can be used when you have unequal variation in your data. Biological data often has unequal variation. This is because if many factors are affecting the variables you are measuring, this means that there is often more than one rate of change between one measured variable and another, due to some of the unmeasured factors. Biological data is also often subject to limiting factors, where the minimum and maximum responses measured may be under quite different constraints. Quantile regression analysis allows you to estimate multiple rates of change in your data, and using this you can often find results that other regression methods may have missed out on.

Another problem biologists often face is that of outliers that mess up their results. Why couldn’t that one fish/fruit fly/mouse behave like the others? Does it make sense to ignore it, or is that bad science?

Robust regression is a method especially developed to deal with influential outliers. If you’re getting really fancy, you can even statistically prove that something is an outlier, by using tests such as the cook’s D statistic. Robust regression does not ignore that one annoying ant/shrub/patient in your data, but it takes into account the fact that it is an outlier and down-weights it accordingly, often helping you to get more useful results.

So before your lack of results gets you down and makes you wonder why you didn’t go for that career in the City, remember that it sometimes takes just a little bit more patience to pull out your breakthrough scientific findings.