Faitheism: the importance of dialogue

Rory Fenton gets influenced by the only book to ever make him cry

Every Christmas for the past several years I sit down and I cry. It’s not that I’m sad; it’s an important tradition. Every Christmas I sit down and watch It’s A Wonderful Life and like a predictable fool each time I’m blinking back salty water. And it’s not just with this film – name a tear jerker and it’s probably worked its magic on me. I even cried at Susan Boyle’s Britain’s Got Talent audition.

But books, now that’s a different story. I’m always so much more engaged by books. They can move and inspire. I’ve changed countless opinions on the strength of a book I’ve read, and found myself in many more people’s shoes than ever I have in films. But a book has yet to win a tear from me. Perhaps it’s the lack of soundtrack, I’ve just never had a pile of paper get the slightest boo or hoo from me, never-mind both at the same time.

That is, until I read Faitheist.

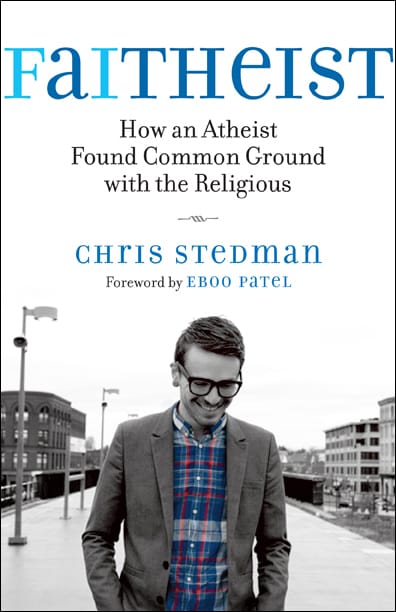

Faitheist is a memoir from Chris Stedman, assistant chaplain at the Harvard Humanist Chaplaincy. I’ve actually known Chris for over two years now, ever since I wrote for his blog, Non Prophet Status. But while I’ve been following his work since, I can’t claim to know him personally, which is why reading his memoir feels so strange, like I’m peeking into his diary. So why does someone just two years older than me have his memoirs out already? It’s because as atheists and the religious debate how to engage one another, his is a very important story to tell.

Chris tells the story of how he went from evangelical Christian to atheist. Such a transition could never be smooth but Chris’ was made all the rockier by his realisation from his early teens that he is gay. He tells of his struggle to reconcile his sexuality with his faith, a struggle that at first he seems to be loosing. He is told that his sexuality is a demon inside him trying to prise him from God. Unable to accept himself, Chris is driven to despair. He describes how one evening, home alone and hating himself for simply being Chris, he took a sharp kitchen knife and locked himself in the family bathroom. Tears and snot smearing his face, he rolled up his left sleeve and practiced, slicing through the warm air above his living skin, the movement he needed to make to end it all. Chris is, of course, still with us but unlike in It’s a Wonderful Life he had no realisation, crouched with his back against the cold shower tiles, of what the world would miss without him – only the thought that suicide would be yet another black mark against his soul made him step out of that shower and replace the knife in its drawer.

This is a very powerful moment and, yes, it moved me to tears. This book and Chris’ life itself could easily, after that episode, have been dedicated to vehemently opposing religion in all its forms. I for one couldn’t blame him yet incredibly the message of the book and Chris’ professional life is one of tolerance; a call for dialogue, not division, between believer and non-believer. Confident now in his atheism, Chris wishes to use his story to highlight intolerance of all kinds – and this includes intolerance within the atheist community for the religious. In his work at Harvard, Chris aims to build constructive dialogue with religious people, focusing on shared values and making genuine, sincere attempts at mutual understanding. Chris stresses that the enemy of secularism is not religion but religious extremism. In combatting this extremism, atheists can find many allies among the religious. Indeed, there simply aren’t enough of us to achieve a good society on our own. We simply must work together and Chris believes it is possible.

If someone who was driven close to suicide by religiously-inspired homophobia can make peace with religion, surely so too can many atheists. The world is simply too complex to divide along the tribal lines of religious and atheist, us and them. In making active efforts to reach across this faith divide we stand to make not just useful allies in fighting the homophobia, sexism and anti-science behind religious extremism, we stand too to build real relationships and gain real friendships. This is Chris’ challenge to his readers and I’m with him on it. Atheists and religious people have too much to gain from sincere dialogue to wallow in lazy stereotyping. As most of us begin to loose the momentum of our two week old New Year’s resolutions, perhaps atheists at large could make a fresh resolution, to make an attempt this year to actively engage a religious person about their beliefs, to try to understand where they come from and see what you might have in common. You could just be surprised. Let the dialogue begin.

Rory tweets as @roryfenton