What would Jesus do?

For nonbelievers to properly engage wth Christians, they must learn about the life of Jesus, says Tom Ravalde

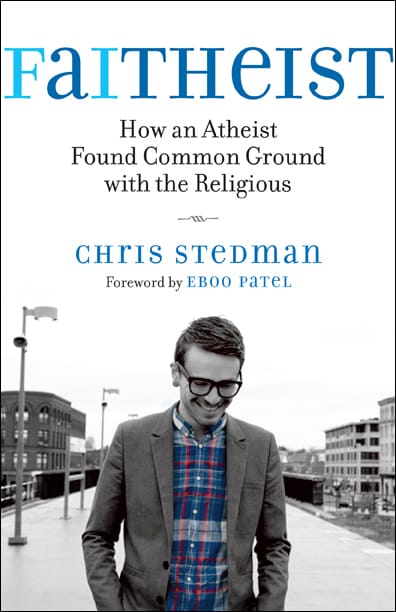

Let the dialogue begin.’ So began Rory Fenton’s thoughtful piece last week – encouraging the religious and irreligious alike to ‘look for the common ground’ and ‘work together’ against extremism for a better society. As a Christian, I welcome this engagement from the (so called) ‘faitheists’ – it’s certainly a refreshing change from the hostile rhetoric spouted by Dawkins et al.

The purpose of this response is to suggest that we need to broaden the horizons of much of our atheist-believer-interfaith dialogue, in order to have a meaningful discussion. What do I mean by that? My worry is that the ‘dialogue’ is always on the terms of the faitheist. The faitheist (understandably) defines the world’s problems as they see them, and then wants to work with religion to oppose them. But what if we view the world’s situation in very different ways? Solutions require a correct understanding of the problem (ever misread an exam question…?!) The Christian world-view has a far deeper explanation of the evil we experience than faitheism allows. The hatred and bigotry described in last week’s article is undoubtedly reprehensible, but it is a manifestation of a more fundamental predicament – a world that’s turned its back on its loving Creator – this is (broadly) what Christians mean by ‘sin’.

Allow me to illustrate what I’m saying with an incident from the life of Jesus Christ – surely any meaningful conversation between atheist and Christian must try to understand him? In Luke’s Gospel, a paralysed man is brought to Jesus – a man who in First Century Israel would have had very limited prospects. At this point, the faitheist would call on people of all religions and none to work together to improve this man’s well-being and life-chances. Shockingly, Jesus sees a need greater than just the physical – saying, ‘My friend, your sins are forgiven’! Jesus tells us our biggest problem is to stand unforgiven before God. His same words also tell us something staggering about himself. The religious leaders are outraged – they consider Jesus a blasphemer: ‘Who can forgive sins but God alone?’ But Jesus is ready to prove his identity by healing the man: ‘I tell you, get up, take your mat and go home.’

Thus, any honest dialogue with Christianity must conclude that Jesus offers a solution in an altogether different category than that offered by human endeavour, meeting a more fundamental need than that which concerns most of us. Whilst conversation remains restricted to faitheist presuppositions, one could be forgiven for thinking that all this talk of ‘dialogue’ and ‘listening’ is merely a pretence. Could it be that faitheism elevates itself above religion, and uses it for its own ends?

So what form should ‘dialogue’ take? Let’s be bold enough to take discussion to the ‘uncommon ground’, asking questions about where the heart of humanity’s problem really lies. Let’s dare to allow the possibility that the solution lies outside of our own abilities, and is found in a supernatural Saviour. Only then can all wrongs truly be righted. If you think that dialogue surrounding these huge questions important, then why not engage with the Christian Union? Friendly dialogue is at the forefront of their agenda. Starting next Monday, they are hosting ‘What if …’ – a week for anyone to explore the life and claims of Jesus, and ask any questions (www.iccu.co.uk/qr). We’d love to see you there.

Let the dialogue continue.