Heatwave at the corona

At least it's warm somewhere

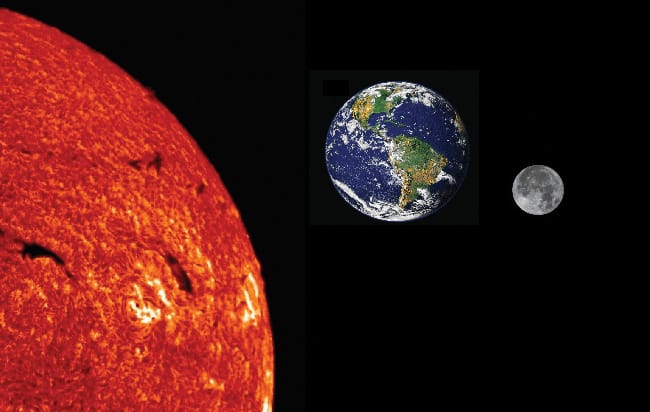

The enormous fusion furnace at the centre of our solar system has been continually belting out light and heat for the past 4.6 billion years since its formation. From the distance the Earth lies from the sun, the solar rays are strong enough to warm the atmosphere to around 20-30°C. The sun’s surface is understandably hotter – with measurements around the 6000°C mark. But one question which has had solar physicists baffled is that its corona – the particulate layer above the surface – has temperatures measuring up to 4,000,000°C. So where’s all this extra heat coming from?

Other than the regular conduction heating from the photosphere below, theories have been put forward that wave heating is a contributor. Jonathan Cirtain, asolar physicist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama explains that sound waves, caused by friction and vibrations within the sun, travel to the surface and deliver energy in the form of heat. Calculations using this model lead to a coronal temperature estimate of only 1,500,000°C, so while this theory is enough in cooler regions of the corona, there is something more happening in the warmer regions which is more than doubling the temperature.

Recently, Cirtain and colleagues have gathered evidence in support of another theory focusing on the sun’s magnetic field. The team sent out a rocket equipped with the High-resolution Coronal Imager (Hi-C) into space last July. The resolution of Hi-C was 0.2 arcseconds; enough to pinpoint features on the sun as small as 150 kilometres (which is comparable to spotting a 5 pence piece from 6 kilometres away).

The camera-telescope was set to measure the extreme parts of the ultraviolet spectrum (with wavelengths at 193 Ångström) that are usually blocked by the Earth’s own atmosphere, with the aim of observing the emission lines of Fe XII atoms (iron atoms which have had 11 electrons in their outer shells ejected). Despite venturing out for a total of 5 minutes, observing a mere 3% of the sun’s surface in this time, two distinct episodes were observed where the magnetic field strongly interacted to produce Fe XII. These contortions of the magnetic ‘braids’ would release enough energy to raise temperatures to as high as 7,000,000°C. It is likely that these interactions occur fairly regularly in magnetically-active areas of the sun, providing overall coronal heating, bringing temperature estimates closer to those measured.

The theory that magnetic braids (strands of magnetic field) were being unravelled and reconnected has been theoretically proposed before, but it lacked substantial evidence. Cirtain and his team have now observed results that can provide firmer backing to the theory.

“The new findings are a tantalizing glimpse of what is possible with such an instrument,” says Peter Cargill, an Imperial College solar physicist. Evenwith this limited glance into solar mechanisms, the new apparatus developed is still enough to test many old hypotheses, and to develop new ones. The next step will hopefully be to develop instruments which can orbit Earth full time, providing a continual stream of data pertaining to the sun and its unusually hot corona.