Influenza research restart

Philippa Skett on the H5N1 moratorium and why caution isn’t bad

"With great power comes great responsibility,” one wise man once said. Although he was unknowingly hinting at those with super powers to tread carefully, it too can be applied in the wider context to those that have the capacity to seriously affect people, either for good or bad. Right now, scientists are the super heroes of the real world (that includes you, so feel free to give yourself a pat on the back right now. Yes, even if you are alone in the Library Café), and with technology accelerating at metaphorical speeds to the point where we had to even redefine the greatest literal speed, great responsibility needs to come into play too.

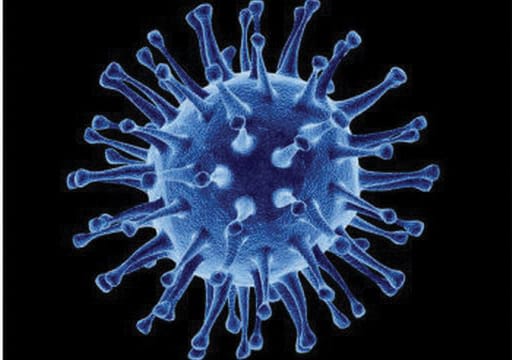

Virologists are such people who have been treading carefully as of late. Last year they imposed upon themselves a moratorium to halt investigations into the avian H5N1 virus – a strain of influenza that is gaining momentum in infection, both in humans and birds, and which could lead to the next pandemic.

Research was initially put on a 60 day hiatus in January 2012 to discuss the biosecurity hazards of the investigations into H5N1. This was sparked by the attempt to publish previous research covering the mutations needed for the virus to allow transmission between ferrets and that could possibly allow for human transmission too. Researchers reasoned that such mutations could just as easily occur in nature, and ignorance will definitely not lead to bliss if we just turn a blind eye. It is better knowing the capacity of the virus and being able to plan for a possible pandemic than feeling threatened by the hazards posed by carrying out such research in the first place, the scientists reasoned.

However, people who opposed this included the National Scientific Advisory Board for Biosecurity sector of the American government, who feared that without censoring the papers, such data could be misused by small labs that could lead to an outbreak of an artificially manufactured, dangerous strain of the pathogen. So despite research picking up considerable speed, the hiatus was introduced.

This “60 day” period halted as of last week however, and a letter from key researchers in the field confirmed that with the WHO, among others, issuing rules concerning biosafety, biosecurity and communication, investigations will nowproceed. Governments and institutions need to approve research before it is taken any further, and a biosafety level of 3 or higher in labs is suggested as necessary for the work. With level 4 being the highest and necessary for investigations into pathogens such as Ebola, another virus whose infection is lethal and currently has no cure, level 3 for a virus with a lethality that is considerably less was considered appropriate.

However, how careful is too careful? “Scientific curiosity,” for want of a better phrase, has never been one to carefully toe the line between what is needed for scientific advancement and the relative views of the general public. Safety concerns, moral conflicts and technological constraints have all been known to hinder research, and it is how researchers conduct themselves when overcoming these barriers, and the responsibility they exhibit, that can add, or diminish considerable value to the papers that they then publish.

Often, a balance has to be struck, and this may be an example of when the balance was just about right. The introduced safety measures may limit the lab numbers that can investigate H5N1, but at least the labs that will be able to will do so without danger to themselves and others. Advancement speed may be stifled, but at least measures like these may stop silly journalists wandering into labs and getting bit by whatever research is on show at the time. Because as much as we might like it, there are not enough Uncle Bens in the world to simply state that with “Great power comes great responsibility,” and hope that that alone does the job.