Looking into the gender balance

We all know about the infamous ‘ratio’ at Imperial. Is it about the STEM subjects, just Imperial, or a worldwide issue? Matt Proctor and Eoghan J Totten investigate

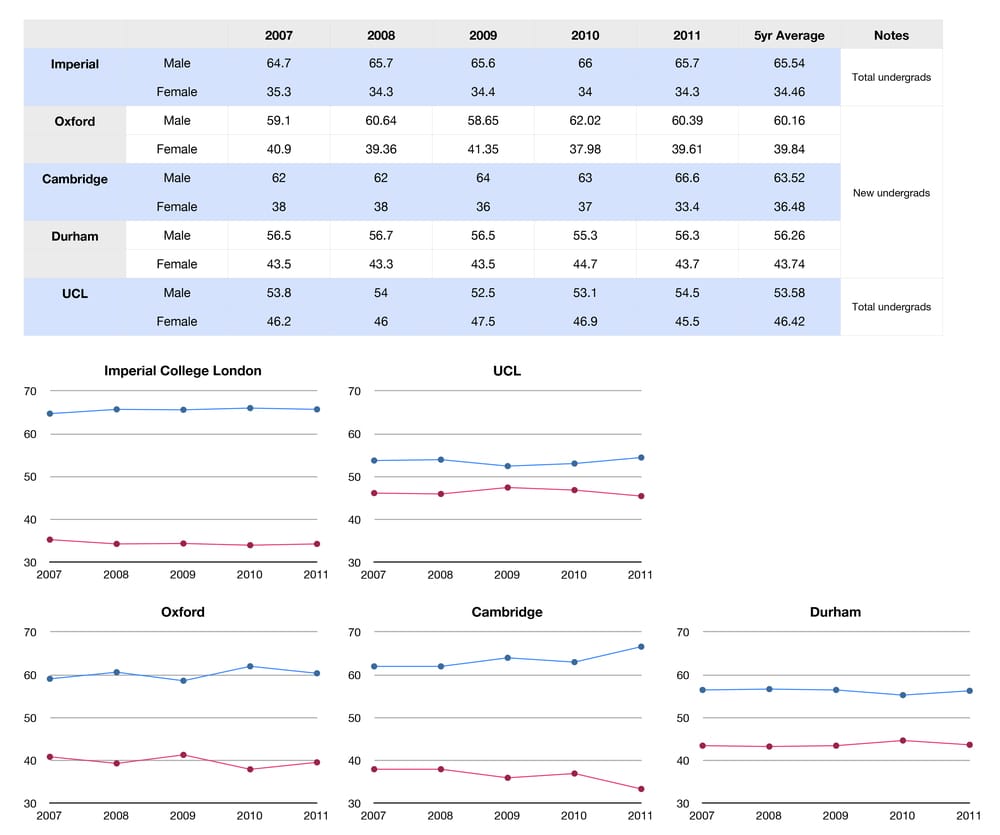

Male undergraduates continue to outnumber females by nearly two to one as revealed by the College Strategic Planning Division. Felix tries to make sense of it all.

The (unsurprising) revelation came to light after the department revealed that for the previous academic year a mere 3,116undergraduates out of 9,080 were female. Some postulate that this is a particular facet of Imperial College but research into other UK universities, conducted by Felix, reveals otherwise. The statistics highlight a strong affinity of the male population with STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics) subjects.

United Kingdom Statistics

‘Oxbridge’, Durham University and University College London exhibit more balanced male: female ratios, with the latter having a 2% female majority overall. Delving deeper into the statistics shows a pivotal change in the ratio for the STEM subjects. The University of Oxford shows that male undergraduates outweigh their female counterparts by a sizeable 22%. Building upon this a mere 33.4% of science undergraduates at the University of Cambridge enrolled for equivalent 2011/2012 academic year were female. The trend for Durham was less polarised but reiterated the correlation. Taken with a pinch of salt these findings demonstrate that the phenomenon is far from localised to Imperial College (being a focus for higher technical education alone), which instead reflects a more generalised third level STEM trend otherwise obscured in different institutions by humanities departments.

Global Statistics

Further investigation conducted by Felix presented the observed male: female ratios as a global trend, extending into Europe, the United States of America and the Far East. Starting off in close proximity to the UK (and closer to my heart – Eoghan) the skewed ratio is observed in Dublin institutions. Out of the 11,844 undergraduates enrolled at Trinity College Dublin for the 2010/2011 academic year 4,856 (41%) were male. On the contrary this does not extend to any of the niche STEM disciplines. The starkest contrast to the college-wide ratio arises within Theoretical Physics; one in thirty scholars are said to be female.

At Princeton University, an archetype of the widely renowned Ivy League, data for the 2011/2012 semesters revealed a 51:49 male: female ratio. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, rather surprisingly, exhibited a similar overall ratio. In spite of this a 2008 study co-ordinated by Michael McGrew-Hardeg, executive editor of The Tech, the leading MIT newspaper, presented profound deviation within certain STEM disciplines. While a staggering 75% of Brain and Cognitive Scientists were revealed to be women they only occupied a third of the available spots in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, alleged to be the most competitive course at MIT. One in four Nuclear Science and Engineering undergraduates were female.

Addressing Asian student trends a minimal 2,543 out of 13,887 undergraduates at the University of Tokyo were female as of May 1st 2011. This may reflect an extensively developed Japanese economy renowned for being centred on the technocrat. The most polarised of all Universities is, in fact, in Europe. Technische Universiteit Delft in Holland once supported a whopping 80:20 male: female majority!

Possible Reasons for Extreme Male:Female Polarisation

The data is overwhelming and persistent. The Imperial College gender ratio has remained approximately unchanged over the previously elapsed decade… but why? The trend extends far beyond third level education and deep into the world of work, despite the efforts of organisations such as WISE (Women in Science, Engineering and Construction), who aspire to achieve a 30% employment rate in the aforementioned STEM fields by 2020. One might argue that this target is somewhat tame; it even suggests a feeling of hesitancy on the part of WISE. This is difficult to rationalise when one considers the driven work ethic of so many women at Imperial College (indeed frequently more driven than many male students). It could be considered a wider pressing, societal problem that requires urgent address.

Some argue the phenomenon to be a simultaneously global and cultural legacy from a bygone era, when all forms of education and employment (not just STEM disciplines) were male-dominated. While it may indeed be controversial to invoke such a possibility of prejudice in a politically correct modern world there is evidence to suggest that it may at least in part be a contributory factor. In a paper produced by PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA) it was deduced that in research-intensive Universities: “Faculty participants rated the male applicant as significantly more competent and hireable than the (identical) female applicant”. This was bolstered by a study undertaken by Yale University which concluded that science professors frequently “regard female undergraduates as less competent than male students with the same accomplishments and skills”. It may be that these findings are categorical and possibly damaging generalisations of a more intricate problem, yet there may be some truth in it.

Male:female postgraduate statistics at Imperial College are closer to 60:40 as revealed by the Strategic Planning Division. Some might argue that the older, more qualified woman is viewed more favourably by selection committees, shaking herself free of any stigmatisation to which she may have been previously and unfairly subjected.

In spite of this many believe that such biascannot persevere in the modern world and look towards other possibilities. Nature versus nurture has often been cited, the trend of discourse moving towards the latter in recent times. It may be that the significant female depletion in STEM university subjects has its origins in early schooling, education and other childhood influences. Boys and girls, rightly or wrongly, are frequently encouraged in differing manners, with the former being directed towards scientific disciplines. It may be that this initiates a negative feedback that extends right through to third level education. The problem may simply be a product of nurture. Addressing this fundamental societal flaw may begin a process of resolution.

Laura Johnston, WSET Chair, was asked for comment. She said that the figures “suggest it’s a country wide problem and that more efforts should be made to encourage girls to persue STEM subjects at degree level overall. Only then will Imperial start to see a proper balance. However, this doesn’t explain the lack of females in more advanced positions within Imperial, eg. PhD students and lecturers, as the ratio of men to women becomes more extreme the higher you go.”

Speculation on the issue need not have an end without wider discussion, thus Felix invites the undergraduate readers (particularly female!) to have their say. Find this article on felixonline.co.uk/ and voice your thoughts on the following pressing issues:

• Why does femaledepletion in STEM disciplines continue to prevail?

• What might be a solution to remedy the gender imbalance?