Jet lag resistance in mice

They don’t suffer like you after a long flight, Fiona Hartley explains

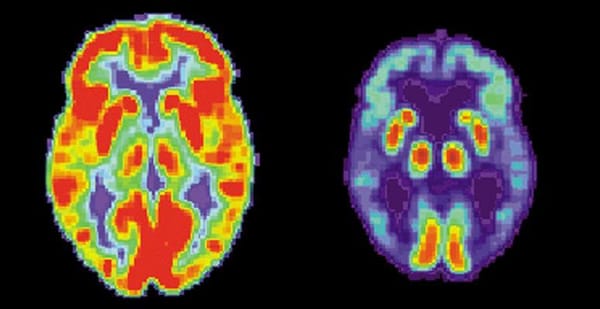

Jet lag is one of those annoyances that stems from living in the modern era. Anyone who has flown to Asia or come home to the UK after an American holiday recognises its unpleasantness. You just have to wait for your body to adjust to the new time zone. When evolution was working on humans, it had no foresight regarding the development of the aeroplane, or that it would play havoc with our body clock by enabling us to travel across the planet in one or two journeys. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) acts as the ‘master clock’ of the human body. In the SCN there are thousands of neurons that regulate the numerous bodily functions that run in a 24-hour cycle, which are called circadian rhythms. These include your core body temperature, urine output, and expression of genes that affect the circadian clock (unsurprisingly called clock genes). The SCN also synchronises these rhythms with the outside world. When we pass through several time zones on a jet plane, our internal clocks become misaligned with external time. Shift-workers have a similar problem. Since some studies suggest that shift work increases the risk of heart disease and certain cancers, a way to combat the physiological effects of misaligned circadian rhythms would be significant to many. Jet lag was first studied in 1965, over a decade after the advent of passenger jet services. Since then the condition has eluded a cure. But Hitoshi Okamura and his colleagues at Kyoto University have made a breakthrough in understanding how the neurons in the SCN communicate. This gives scientists greater hope that there could one day be a treatment for the symptoms of jet lag. The group published their study in Science last week. Arginine vasopressin (AVP) is a hormone released by around half of the neurons in the mouse SCN and detected by several receptor proteins. There are also AVP receptors in the human SCN. In a population of mice, the researchers deleted two AVP receptor genes: V1a and V1b. This made the mice unable to respond to AVP. The group then placed this genetically-modified population and a wild-type population of mice on a 12-hour day, 12-hour night light cycle for two weeks. When the light cycle was changed to mimic an eight hour time difference, as occurs when humans suffer from jet lag, the ‘normal’ mice took many days to readjust to the new rhythm. However, the mice lacking in AVP receptors re-entrained to the new light-dark cycle at least twice as quickly. When the V1a and V1b receptors in wild-type mice were temporarily blocked with chemicals they too recovered from their induced jet lag quickly (though not quite as quickly), confirming that the missing receptors are responsible for the accelerated rate of recovery. In addition, the mutant mice did not suffer any obvious ill-effects to their internal clocks. Their circadian rhythms maintained a normal 24-hour cycle. As with a mechanical clock, the SCN was able to uphold good time-keeping internally whilst being easily resettable in response to external solar time. It will still be very difficult to create a magic pill capable of treating jet lag thanks to the presence of AVP receptors throughout the body. Any drug disrupting the receptors in the SCN would also disrupt receptors that control blood pressure and water retention, the better-known functions of AVP. But the hope is there, and the knowledge should help scientists to further investigate the intricacies of the SCN.

DOI: 10.1126/science.1238599