Scientists go back to work

Jamie Rickman on the impact of the US shutdown

The 16 day US government shut-down ended last week with an uneasy truce. Obama’s refusal to accept the House Republican’s condition of delaying Obamacare led to the closure of many federal science institutions, painfully elucidating the instability of government funded science in America.

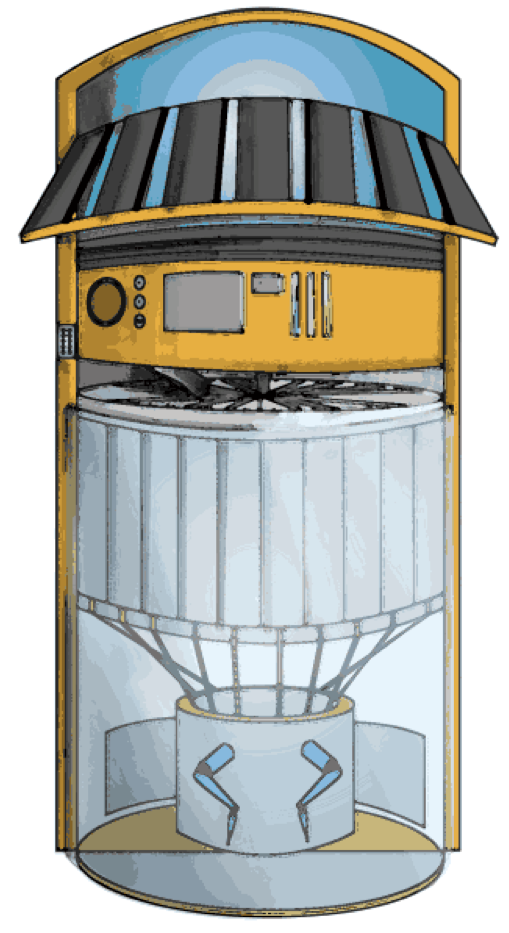

The full effects of the shutdown on the scientific community will perhaps never be known. The tangential investigations and light-bulb moments of inspiration that bring break-throughs require momentum, and that has been lost. Overcoming the inertia post shut-down will be a long and difficult process. But the immediate impacts are obvious. Basic lab operations in cancer research and HIV were stopped and clinical trials could not be initiated. The National Institute of Health (NIH) were forced to turn away around 200 patients a week awaiting treatment, roughly 30 of whom were children. For those with degenerative illnesses this delay could cause irreparable damage. Specially bred lab mice at the NIH needing constant monitoring have died; these unique strains will be expensive and time-consuming to restart. NASA could not undertake vital checks on the new James Webb Space Telescope which is set to replace Hubble, some of which may never be completed before launch. An environmental programme in the Antarctic has missed a crucial research window; it’ll have to wait another year.

Scientific research is never immune to ill circumstance; faulty equipment and bad conditions can similarly disrupt progress, so one should perhaps be wary of sensationalising the lasting effects of this moratorium. But there is something deeply unsettling in the balance of power between scientists in the US and the government who sign their checks.

75% of NIH employers were sent home, or furloughed, with no guarantee of back pay. A source inside the NIH, warned against speaking to the press, lamented the demoralisation this caused in her lab for those deemed ‘inessential’. For the majority of workers on low pay and 10-12 hour days this kind of financial insecurity and lack of recognition is untenable, forcing them to consider finding work elsewhere. She explained that her biggest frustration was that she would rather have gone to work without pay and continue research than let her mice die. During the 1995 shutdown this was allowed, while last week it was illegal to check work emails let alone enter a lab. This strange and obtuse piece of legislation not only expresses a flagrant disregard for the value of science but a fundamental misunderstanding of the way it operates. When it did enter the debate in Congress, the only arguments that stood ground against the tide of republican indifference reduced science to a political asset; the lost time could mean the US losing its competitive edge over China for example. In this landscape of brinkmanship politics more shut-downs are expected, and the damaging effects will be cumulative. Some would say the future of federally funded science in the US looks bleak.