To sleep, perchance to clean (your brain)

After hundreds of years of hypothesis, the primary function for sleep may now have been discovered.

After hundreds of years of hypothesis, the primary function for sleep may now have been discovered. Maiken Nedergaard and colleagues this week released a paper detailing how in sleep the brain clears away waste proteins linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s that build up in the space between brain cells.

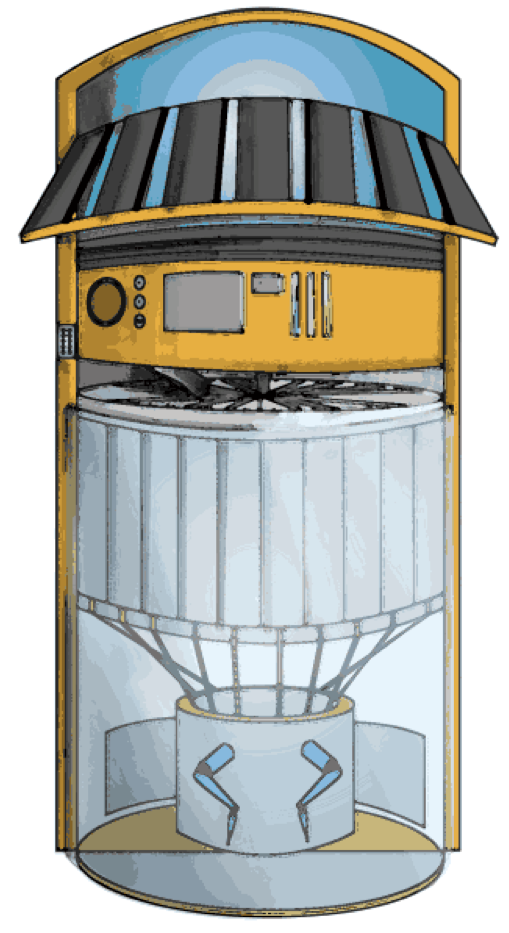

The recently discovered network of tiny pathways within the brain that allow these proteins to be cleared is called the glymphatic system, similar to the lymphatic system in the body that flushes toxic by-products out of the blood and into the liver. The pathways circulate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) into the spaces between cells in the brain, removing the toxic proteins.

It had been noted before that the level of these proteins is higher in awake animals than in sleeping ones, but that was previously thought to be because they were produced at a higher rate when the brain is awake. This team investigated the alternate possibility that the glymphatic system is more active when animals are sleeping.

They worked with anaesthetised, awake and sleeping mice, whose CSF was injected with green dye when their brain waves indicated that they were asleep, and red dye when awake. The path of the dyes through the brain was then followed, and it was found that large amounts of CSF were taken into the brain when the mice were asleep, but not when awake. Indeed, when the mice were woken, the influx of CSF dropped by approximately 95%.

They also tested the clearing of injected proteins, and found they cleared twice as quickly when the mice were asleep. Both of these effects seem to be due to the channels that carry the fluid expanding by 60% in asleep and anesthetised mice.

It still remains to be seen whether the build-up of these toxic proteins actually regulate sleep — whether they make you more drowsy the more of them there are — but this paper does appear to reveal, at last, one very important function of sleep. DOI: 10.1126/science.1241224