Diagnosing Down’s Syndrome

Utsav Radia on the new antenatal blood test and its potential to detect the genetic disorder before birth

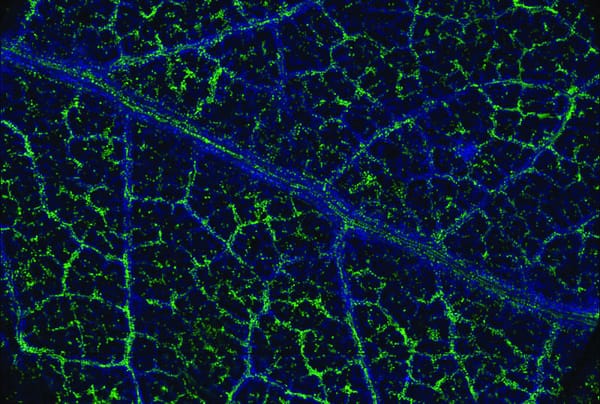

A new antenatal blood test, developed by Professor Kypros Nicolaides and his team of researchers at King’s College London in collaboration with University College London Hospital, with the potential to diagnose Down’s Syndrome in developing foetuses, is being considered for trial in the NHS. Down’s Syndrome, also called Trisomy 21, is a genetic condition affecting around 750 (1 per 1000) newborns in the UK each year and is one of the most common genetic causes of learning disabilities. Trisomy 21 is caused by the presence of all or part of an extra copy of chromosome 21 in a person’s DNA. Down’s patients suffer from many physiological disabilities such as hypotonia (reduced muscle tone), sandal toe, congenital heart defects, brachydactyly (short fingers), a flat facial profile and skeletal deformities. Down’s patients struggle with activities like walking, sitting, standing, reading etc. There is no current cure for Down’s Syndrome but support is given to help patients lead a healthier, active and independent lifestyle. Current antenatal screening involves a combined test done in the first trimester between the 11th and 13th weeks of pregnancy and includes ultrasound screening (used to measure thickness of tissue at the back of the foetus neck) and a hormonal test of the mother’s blood (to detect high levels of Human Chorionic Gonadotrophin and Estriol). The results of these tests along with the mother’s age are used to predict the risk to the foetus – this method picks up about 90% of cases. For high-risk pregnancies, further methods of testing include: Chorionic Villus Sampling, which involves taking cell samples from the placenta; and, Amniocentesis, where a sample of amniotic fluid is taken. These are subsequently analysed for presence of the extra chromosome 21 copy. However, both methods are invasive and carry a 1% chance of miscarriage and a false positive chance of 3-4%. The new antenatal blood test uses ‘foetal cell free’ (cf) DNA that is present in the mother’s blood to scan for the presence of the extra chromosome 21. The study, published in the journal ‘Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology’, shows that in the 1005 pregnancies trialed at 10 weeks, there was a much lower false positive rate of 0.1% and a 99% rate of Down’s Syndrome detection. Currently, this test is only being offered privately and to any pregnant women who volunteer to participate in the ongoing trials. Professor Nicolaides added that this new technique “if offered across the UK, would have the potential to increase the diagnosis rate from 1,000 cases to almost all of the 1,200 which occur every year”. Professor Lyn Chitty of Great Ormond Street Hospital confirms that this could “very significantly reduce the number of invasive tests” as only 0.5% of cases that had the blood test required any form of invasive testing. Early detection of the condition in foetuses can help parents to plan ahead and also gives them time to learn more about the condition and how they can help their child. However, at £400 a test, it seems highly unlikely that will be readily available through the NHS any time soon.